It is useful to be able to visualise the commits timeline, aka the revision graph.

Git commits form a timeline, as each corresponds to a point in time when you asked Git to take a snapshot of your working directory. Each commit links to at least one previous commit, forming a structure that we can traverse.

A timeline of commits is called a branch. By default, Git names the initial branch master -- though many now use main instead. You'll learn more about branches in future lessons. For now, just be aware that the commits you create in a new repo will be on a branch called master (or main) by default.

gitGraph

%%{init: { 'theme': 'default', 'gitGraph': {'mainBranchName': 'master (or main)'}} }%%

commit id: "Add fruits.txt"

commit id: "Update fruits.txt"

commit id: "Add colours.txt"

commit id: "..."

Git can show you the list of commits in the Git history.

Preparation Use the things repo you created in a previous lesson. Alternatively, you can use the commands given below to create such a repo from scratch.

mkdir things # create a folder for the repo

cd things

git init

echo -e "apples\nbananas\ncherries\ndragon fruits" > fruits.txt

git add fruits.txt

git commit -m "Add fruits.txt"

You can copy-paste a list of commands (such as commands given above), including any comments, to the terminal. After that, hit enter to run them in sequence.

1 View the list of commits, which should show just the one commit you created just now.

You can use the git log command to see the commit history.

git log

commit ... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add fruits.txt

Use the Q key to exit the output screen of the git log command.

Note how the output has some details about the commit you just created. You can ignore most of it for now, but notice it also shows the commit message you provided.

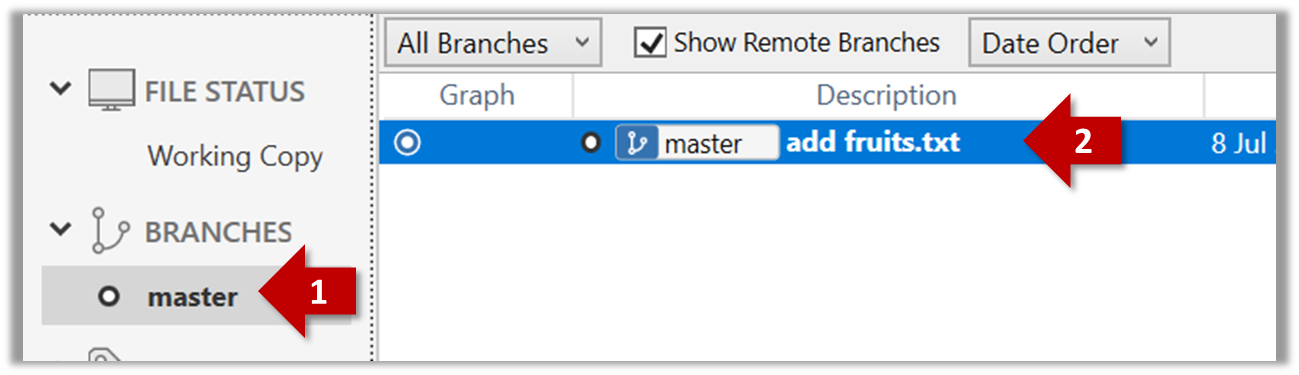

Expand the BRANCHES menu and click on the master to view the history graph, which contains only one node at the moment, representing the commit you just added. For now, ignore the label master attached to the commit.

2 Create a few more commits (i.e., a few rounds of add/edit files → stage → commit), and observe how the list of commits grows.

Here is an example list of bash commands to add two commits while observing the list of commits

echo "figs" >> fruits.txt # add another line to fruits.txt

git add fruits.txt # stage the updated file

git commit -m "Insert figs into fruits.txt" # commit the changes

git log # check commits list

echo "a file for colours" >> colours.txt # add a colours.txt file

echo "a file for shapes" >> shapes.txt # add a shapes.txt file

git add colours.txt shapes.txt # stage both files in one go

git commit -m "Add colours.txt, shapes.txt" # commit the changes

git log # check commits list

The output of the final git log should be something like this:

commit ... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

commit ...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Insert figs into fruits.txt

commit ...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add fruits.txt

SIDEBAR: Working with the 'less' pager

Some Git commands — such as git log— may show their output through a pager. A pager is a program that lets you view long text one screen at a time, so you don’t miss anything that scrolls off the top. For example, the output of git log command will temporarily hide the current content of the terminal, and enter the pager view that shows output one screen at a time. When you exit the pager, the git log output will disappear from view, and the previous content of the terminal will reappear.

command 1

output 1

git log

→

commit f761ea63738a...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add colours.txt

By default, Git uses a pager called less. Given below are some useful commands you can use inside the less pager.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

q | Quit less and return to the terminal |

↓ or j | Move down one line |

↑ or k | Move up one line |

Space | Move down one screen |

b | Move up one screen |

G | Go to the end of the content |

g | Go to the beginning of the content |

/pattern | Search forward for pattern (e.g., /fix) |

n | Repeat the last search (forward) |

N | Repeat the last search (backward) |

h | Show help screen with all less commands |

If you’d rather see the output directly, without using a pager, you can add the --no-pager flag to the command e.g.,

git --no-pager log

It is possible to ask Git to not use less at all, use a different pager, or fine-tune how less is used. For example, you can reduce Git's use of the pager (recommended), using the following command:

git config --global core.pager "less -FRX"

Explanation:

-F: Quit if the output fits on one screen (don’t show pager unnecessarily)-R: Show raw control characters (for coloured Git output)-X: Keep content visible after quitting the pager (so output stays on the terminal)

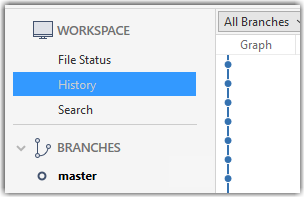

To see the list of commits, click on the History item (listed under the WORKSPACE section) on the menu on the right edge of Sourcetree.

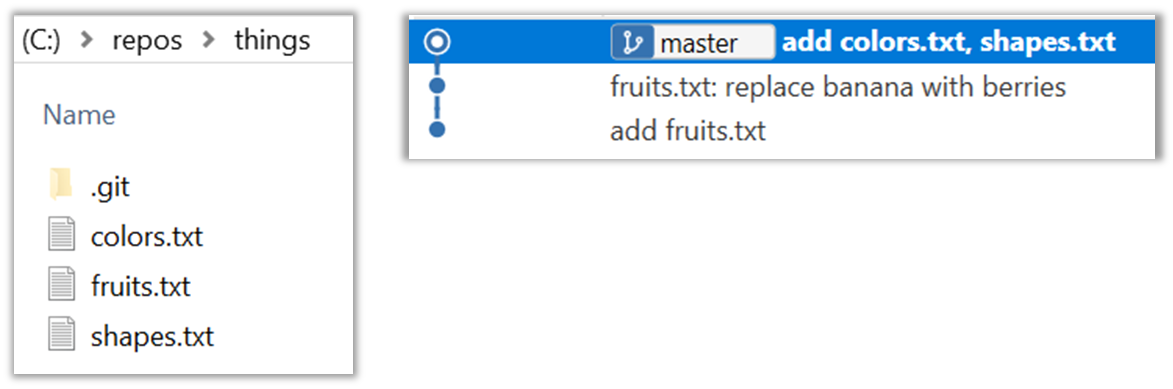

After adding two more commits, the list of commits should look something like this:

done!

The Git data model consists of two types of entities: objects and refs (short for references). In this lesson, you will encounter examples of both.

A Git revision graph is a visualisation of a repo's revision history, consisting of one or more branches. First, let us learn to work with simpler revision graphs consisting of one branch, such as the one given below.

- Nodes in the revision graph represent commits. A commit is one of four main types of Git objects. For completeness, the other three are:

- blob (short for binary large object): stores the contents of a file

- tree: represents a directory and records the hierarchy of its contents by referencing blobs and other trees

- tag (specifically, annotated tag): a label-like object that can store additional metadata and point to a specific commit

- A commit is identified by its SHA value. A SHA (Secure Hash Algorithm) value is a unique identifier generated by Git to represent each commit. It is produced by using SHA-1 (i.e., one of the algorithms in the SHA family of cryptographic hash functions) on the entire content of the commit. It's a 40-character hexadecimal string (e.g.,

f761ea63738a67258628e9e54095b88ea67d95e2) that acts like a fingerprint, ensuring that every commit can be referenced unambiguously. That is, every commit has a unique SHA-1 hash value. - A commit is a full snapshot of the working directory, constructed based on the previous commit, and the changes staged. That means each commit (except the initial commit) is based on a another 'parent' commit. Some commits can have multiple parent commits -- we’ll cover that later.

Given every commit has a unique hash, the commit hash values you see in our examples will be different from the hash values of your own commits, for example, when following our hands-on practicals.

Edges in the revision graph represent links between a commit and its parent commit(s). In some revision graph visualisations, you might see arrows (instead of lines) showing how each commit points to its parent commit.

Git uses refs to name and keep track of various points in a repository’s history. These refs are essentially 'named-pointers' that can serve as bookmarks to reach a certain point in the revision graph using the ref name.

In the revision graph above, there are two refs master and ←HEAD.

- master is a branch ref. A branch ref points to the latest commit on a branch. In this visualisation, the commit shown alongside the ref is the one it points to i.e.,

C3.

When you create a new commit, the branch ref of the branch moves to the new commit. - ←HEAD is a special ref that typically points to the current branch and moves along with that branch ref. In this example, it is pointing to the

masterbranch.

In certain cases, theHEADmay point directly to a specific commit instead of a branch. This situation is called a "detachedHEAD", which will be covered in a later lesson.

Target Use Git features to examine the revision graph of a simple repo.

Preparation Use a repo with just a few commits and only one branch.

1 First, use a simple git log to view the list of commits.

git log

commit f761ea63738a... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

commit 2bedace69990...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add figs to fruits.txt

commit d5f91de5f0b5...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Fri ...

Add fruits.txt

Given below the visual representation of the same revision graph. As you can see, the log output shows the refs slightly differently, but it is not hard to see what they mean.

2 Use the --oneline flag to get a more concise view. Note how the commit SHA has been truncated to first seven characters (first seven characters of a commit SHA is enough for Git to identify a commit).

git log --oneline

f761ea6 (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

3 The --graph flag makes the result closer to a graphical revision graph. Note the * that indicates a node in a revision graph.

git log --oneline --graph

* f761ea6 (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

* 2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

* d5f91de Add fruits.txt

The --graph option is more useful when examining a more complicated revision graph consisting of multiple parallel branches.

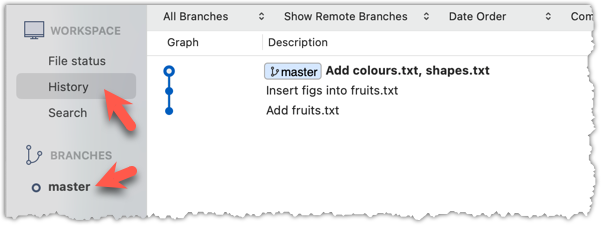

Click the History to see the revision graph.

- In some versions of Sourcetree, the

HEADref may not be shown -- it is implied that theHEADref is pointing to the same commit the currently active branch ref is pointing.

done!