Introduction to Revision Control

Before learning about Git, let us first understand what revision control is.

Given below is a general introduction to revision control, adapted from bryan-mercurial-guide:

Revision control is the process of managing multiple versions of a piece of information. In its simplest form, this is something that many people do by hand: every time you modify a file, save it under a new name that contains a number, each one higher than the number of the preceding version.

Manually managing multiple versions of even a single file is an error-prone task, though, so software tools to help automate this process have long been available. The earliest automated revision control tools were intended to help a single user to manage revisions of a single file. Over the past few decades, the scope of revision control tools has expanded greatly; they now manage multiple files, and help multiple people to work together. The best modern revision control tools have no problem coping with thousands of people working together on projects that consist of hundreds of thousands of files.

There are a number of reasons why you or your team might want to use an automated revision control tool for a project.

- It will track the history and evolution of your project, so you don't have to. For every change, you'll have a log of who made it; why they made it; when they made it; and what the change was.

- It makes it easier for you to collaborate when you're working with other people. For example, when people more or less simultaneously make potentially incompatible changes, the software will help you to identify and resolve those conflicts.

- It can help you to recover from mistakes. If you make a change that later turns out to be an error, you can revert to an earlier version of one or more files. In fact, a good revision control tool will even help you to efficiently figure out exactly when a problem was introduced.

- It will help you to work simultaneously on, and manage the drift between, multiple versions of your project.

Most of these reasons are equally valid, at least in theory, whether you're working on a project by yourself, or with a hundred other people.

A revision is the state of a piece of information at a specific point in time, resulting from changes made to it e.g., if you modify the code and save the file, you have a new revision (or a new version) of that file. Some seem to use this term interchangeably with version while others seem to distinguish the two -- here, let us treat them as the same, for simplicity.

Revision Control Software (RCS) are the software tools that automate the process of Revision Control i.e., managing revisions of software . RCS are also known as Version Control Software (VCS), and by a few other names.

Git is the most widely used RCS today. Other RCS tools include Mercurial, Subversion (SVN), Perforce, CVS (Concurrent Versions System), Bazaar, TFS (Team Foundation Server), and Clearcase.

Github is a web-based project hosting platform for projects using Git for revision control. Other similar services include GitLab, BitBucket, and SourceForge.

Putting a Folder Under Git's Control

To be able to save snapshots of a folder using Git, you must first put the folder under Git's control by initialising a Git repository in that folder.

Normally, we use Git to manage a revision history of a specific folder, which gives us the ability to revision-control any file in that folder and its subfolders.

To put a folder under the control of Git, we initialise a repository (short name: repo) in that folder. This way, we can initialise repos in different folders, to revision-control different clusters of files independently of each other e.g., files belonging to different projects.

You can follow the hands-on practical below to learn how to initialise a repo in a folder.

What is this? HANDS-ON panels contain hands-on activities you can do as you learn Git. If you are new to Git, we strongly recommend that you do them yourself (even if they appear straightforward), as hands-on usage will help you internalise the concepts and operations better.

Preparation Choose a folder to put under Git's control. The folder may or may not contain any files. For this practical, let us create a folder named things for this purpose.

You can get the Git-Mastery app to for doing this practical, or create the sandbox manually. Instructions for the both options are given below.

To prepare the sandbox for this practical:

- Navigate inside the

gitmastery-exercisesfolder. - Run

gitmastery download hp-init-repocommand.

The sandbox will be set up inside the gitmastery-exercises/hp-init-repo folder.

Assuming you have a folder named git-practicals that you wish to use for doing Git hands-on practicals in, you can run the following commands.

cd git-practicals

mkdir things

Avoid putting Git repos inside cloud-synced (e.g., OneDrive, Dropbox) folders. Reason: Multiple tools trying to detect/sync changes in the same folder can cause conflicts and unexpected behaviors.

If you want to access project files from multiple computers, use Git to do that (rather than cloud syncing tools).

1 Then cd into it.

cd things

2 Run the git status command to check the status of the folder.

git status

fatal: not a git repository (or any of the parent directories): .git

Don't panic. The error message is expected. It confirms that the folder currently does not have a Git repo.

3 Now, initialise a repository in that folder.

Use the command git init which should initialise the repo.

git init

Initialized empty Git repository in things/.git/

The output might also contain a hint about a name for an initial branch (e.g., hint: Using 'master' as the name for the initial branch ...). You can ignore that for now.

Note how the output mentions the repo being created in things/.git/ (not things/). More on that later.

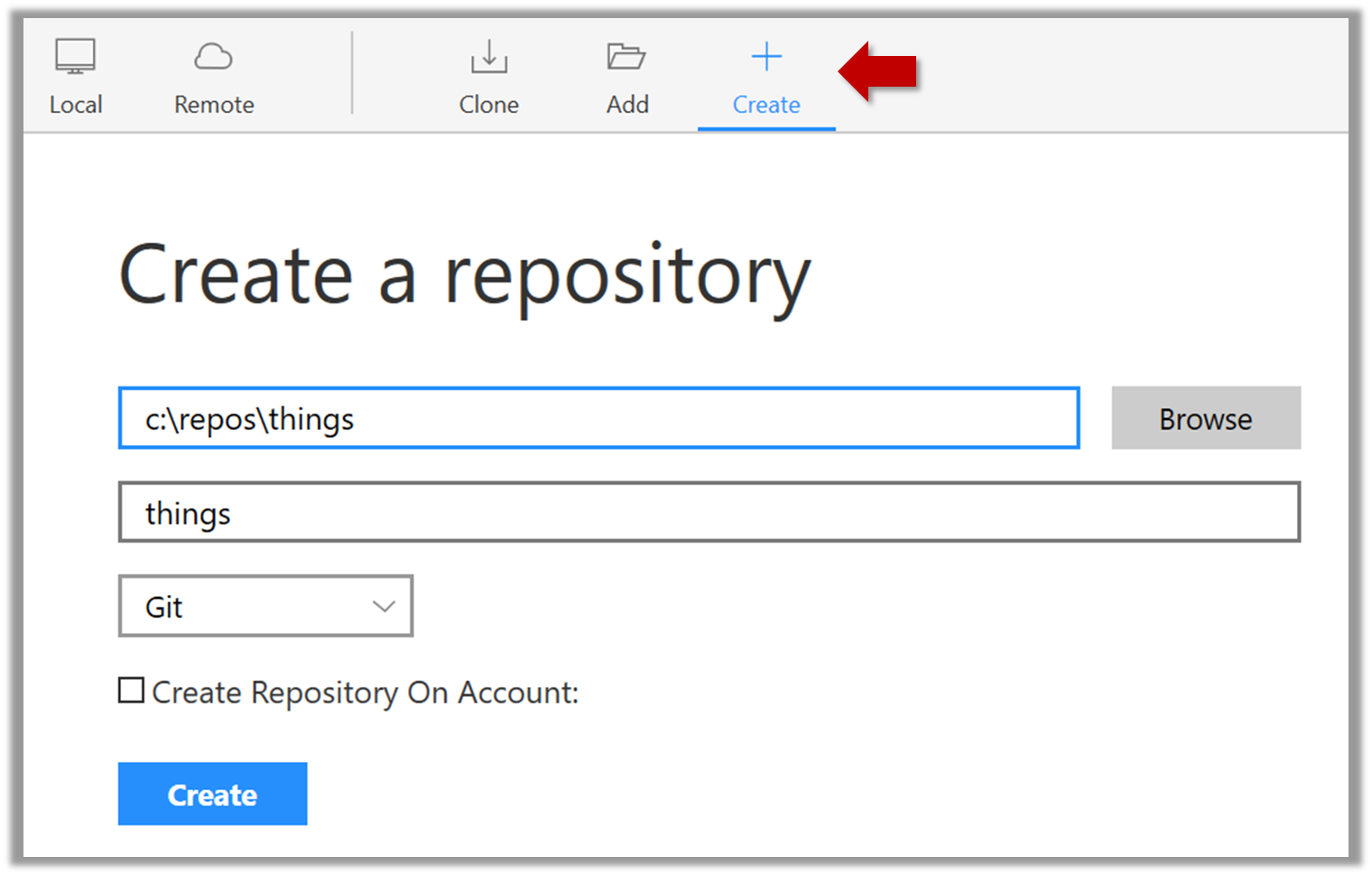

Windows: Click

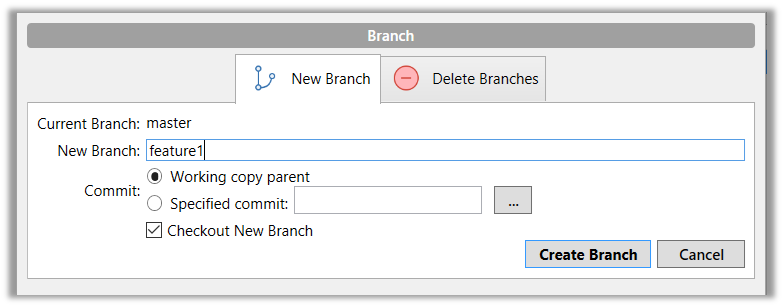

File→Clone/New…→ Click on+ Createbutton on the top menu bar.

Enter the location of the directory and clickCreate.Mac:

New...→Create Local Repository(orCreate New Repository) → Click...button to select the folder location for the repository → click theCreatebutton.

done!

Initialising a repo results in two things:

- First, Git now recognises this folder as a Git repository, which means it can now help you track the version history of files inside this folder.

To confirm, you can run the git status command. It should respond with something like the following:

git status

On branch master

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

Don't worry if you don't understand the output (we will learn about them later); what matters is that it no longer gives an error message as it did before.

done!

- Second, Git created a hidden subfolder named

.gitinside thethingsfolder. This folder will be used by Git to store metadata about this repository.

A Git-controlled folder is divided into two main parts:

- The repository – stored in the hidden

.gitsubfolder, which contains all the metadata and history. - The working directory – everything else in that folder, where you create and edit files.

Specifying What to include in a Snapshot

To save a snapshot, you start by specifying what to include in it, also called staging.

Git considers new files that you add to the working directory as 'untracked' i.e., Git is aware of them, but they are not yet under Git's control. The same applies to files that existed in the working folder at the time you initialised the repo.

A Git repo has an internal space called the staging area which it uses to build the next snapshot. Another name for the staging area is the index.

We can stage an untracked file to tell Git that we want its current version to be included in the next snapshot (in Git terminology, such a snapshot is called a commit). Once you stage an untracked file, it becomes 'tracked' (i.e., under Git's control). A staged file can be unstaged to indicate that we no longer want it to be included in the next snapshot.

In the example below, you can see how staging files change the status of the repo as you go from (a) to (c).

staging area

[empty]

other metadata ...

├─ fruits.txt (untracked!)

└─ colours.txt (untracked!)

(a) State of the repo, just after initialisation, and creating two files. Both are untracked.

staging area

└─ fruits.txt

other metadata ...

├─ fruits.txt (tracked)

└─ colours.txt (untracked!)

(b) State after staging

fruits.txt.staging area

├─ fruits.txt

└─ colours.txt

other metadata ...

├─ fruits.txt (tracked)

└─ colours.txt (tracked)

(c) State after staging

colours.txt.preparation

You can continue using the sandbox created in the previous hands-on practical, or,

1 Add a file (e.g., fruits.txt) to the things repo folder.

Here is an easy way to do that with a single terminal command.

echo -e "apples\nbananas\ncherries" > fruits.txt

apples

bananas

cherries

Windows users: Use the git-bash terminal to run the above command (and all commands given in these lessons). Some of them might not work in other terminals such as the PowerShell.

To see the content of the file, you can use the cat command:

cat fruits.txt

2 Stage the new file.

2.1 Check the status of the folder using the git status command.

git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

fruits.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

2.2 Use the git add <file> command to stage the file.

git add fruits.txt

You can replace the add with stage (e.g., git stage fruits.txt) and the result is the same (they are synonyms).

Windows users: When using the echo command to write to text files from Git Bash, you might see a warning LF will be replaced by CRLF the next time Git touches it when Git interacts with such a file. This warning is caused by the way line endings are handled differently by Git and Windows. You can simply ignore it, or suppress it in future by running the following command:

git config --global core.safecrlf false

2.3 Check the status again. You can see the file is no longer 'untracked'.

git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: fruits.txt

As before, don't worry if you don't understand the content of the output (we'll unpack it in a later lesson). The point to note is that the file is no longer listed as 'untracked'.

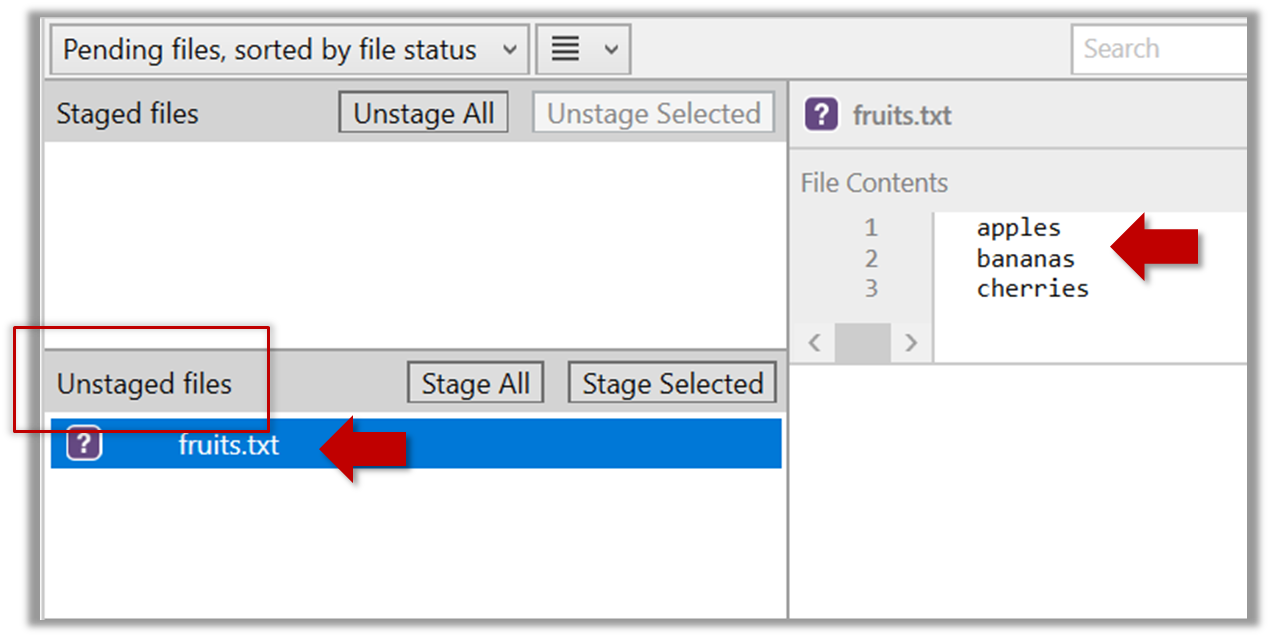

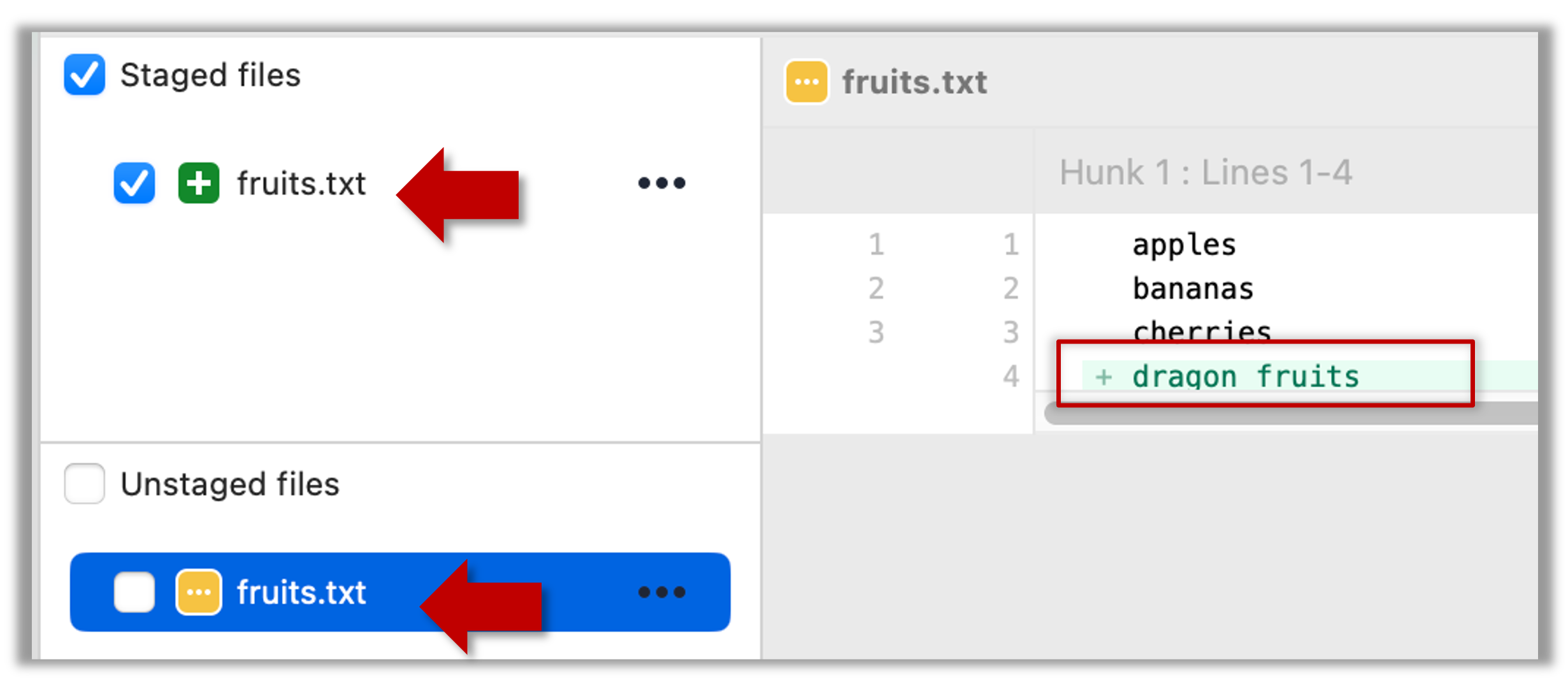

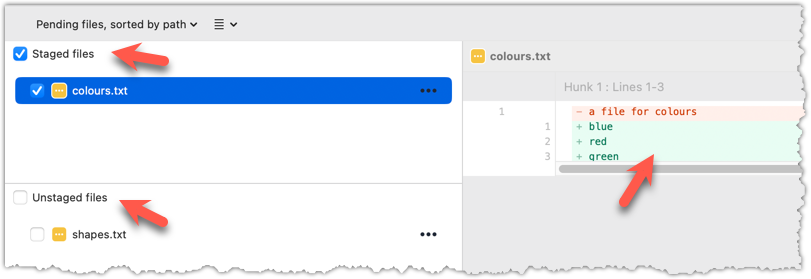

2.1 Note how the file is shown as ‘unstaged’. The question mark icon indicates the file is untracked.

If the newly-added file does not show up in Sourcetree UI, refresh the UI (: F5

| ⌥+R)

Sourcetree screenshots/instructions: vs

Note that Sourcetree UI can vary slightly between Windows and Mac versions. Some of the screenshots given in our lessons are from the Windows version while some are from the Mac version.

In som cases, we have specified how they differ.

In other cases, you may need to adapt if the given screenshots/instructions are slightly different from what you are seeing in your Sourcetree.

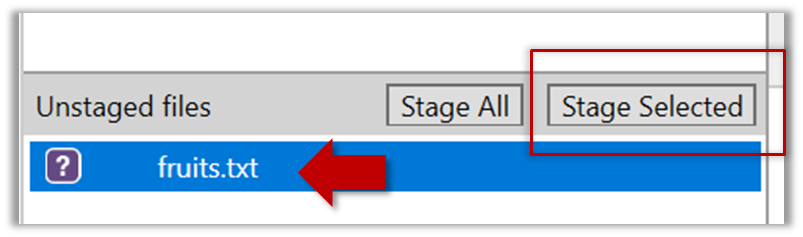

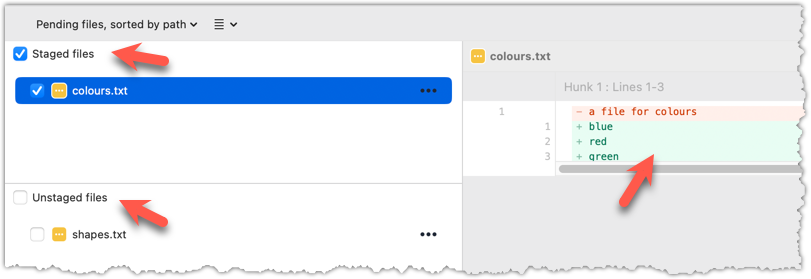

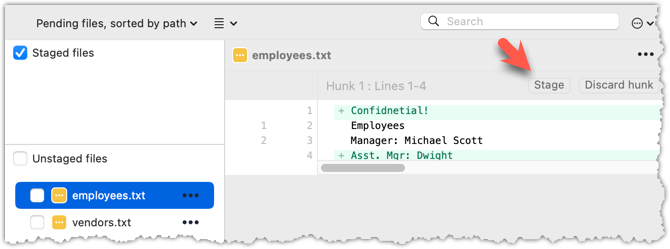

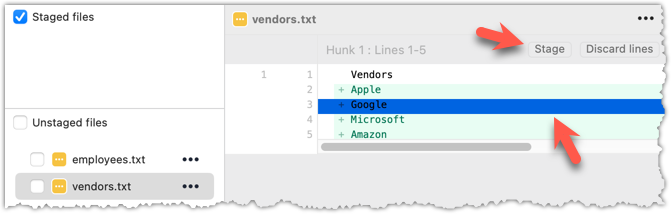

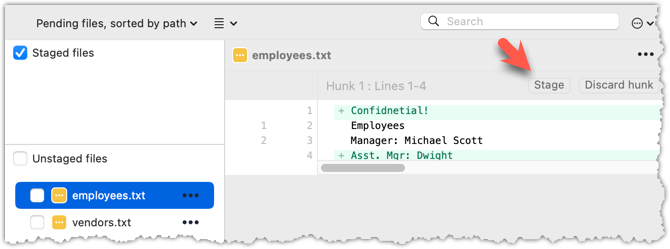

2.2 Stage the file:

Select the fruits.txt and click on the Stage Selected button.

Staging can be done using tick boxes or the ... menu in front of the file.

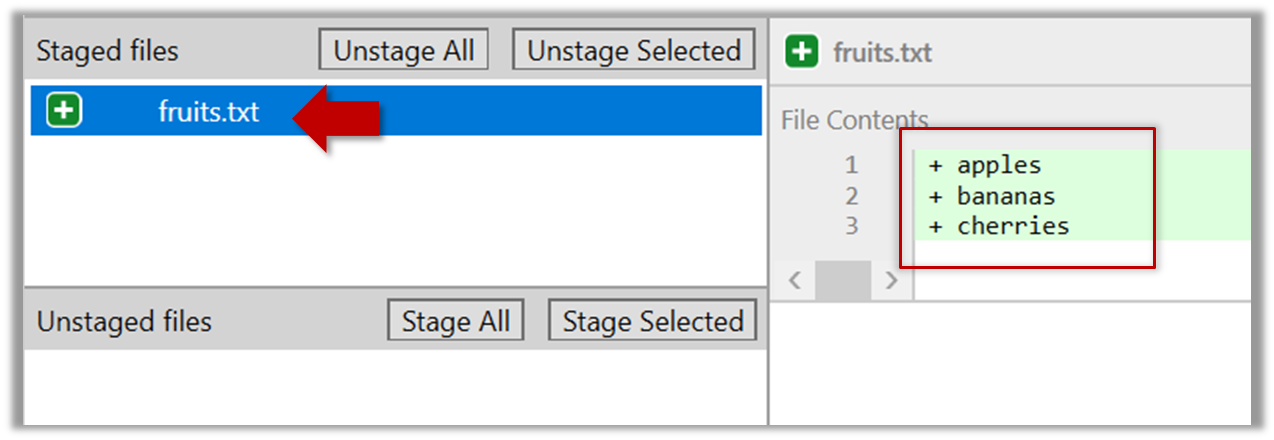

2.3 Note how the file is staged now i.e., fruits.txt appears in the Staged files panel now.

If Sourcetree shows a \ No newline at the end of the file message below the staged lines (i.e., below the cherries line in the above screenshot), that is because you did not hit enter after entering the last line of the file (hence, Git is not sure if that line is complete). To rectify, move the cursor to the end of the last line in that file and hit enter (like you are adding a blank line below it). This new change will now appear as an 'unstaged' change. Stage it as well.

done!

If you modify a staged file, it goes into the 'modified' state i.e., the file contains modifications that are not present in the copy that is waiting (in the staging area) to be included in the next snapshot. If you wish to include these new changes in the next snapshot, you need to stage the file again, which will overwrite the copy of the file that was previously in the staging area.

The example below shows how the status of a file changes when it is modified after it was staged.

staging area

Alice

other metadata ...

Alice

(a) The file names.txt is staged. The copy in the staging area is an exact match to the one in the working directory.

staging area

Alice

other metadata ...

Alice

Bob

(b) State after adding a line to the file. Git indicates it as 'modified' because it now differs from the version in the staged area.

staging area

Alice

Bob

other metadata ...

Alice

Bob

(c) After staging the file again, the staging area is updated with the latest copy of the file, and it is no longer marked as 'modified'.

preparation

You can continue using the sandbox created in the previous hands-on practical, or,

1 First, add another line to fruits.txt, to make it 'modified'.

Here is a way to do that with a single terminal command.

echo "dragon fruits" >> fruits.txt

apples

bananas

cherries

dragon fruits

2 Now, verify that Git sees that file as 'modified'.

Use the git status command to check the status of the working directory.

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: fruits.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: fruits.txt

Note how fruits.txt now appears twice, once as new file: ... (representing the version of the file we staged earlier, which had only three lines) and once as modified: ... (representing the latest version of the file which now has a fourth line).

Note how fruits.txt appears in the Staged files panel as well as 'Unstaged files'.

3 Stage the file again, the same way you added/staged it earlier.

4 Verify that Git no longer sees it as 'modified', similar to step 2.

done!

Staging applies regardless of whether a file is currently tracked.

- Staging an untracked file will both begin tracking the file and include it in the next snapshot.

- Staging an already tracked file will simply mark its current changes for inclusion in the next commit.

Git also supports fine-grained selective staging i.e., staging only specific changes within a file while leaving other changes to the same file unstaged. This will be covered in a later lesson.

Git does not track empty folders. It tracks only folders that contain tracked files.

You can test this by adding an empty subfolder inside the things folder (e.g., things/more-things) and checking if it shows up as 'untracked' (it will not). If you add a file to that folder (e.g., things/more-things/food.txt) and then staged that file (e.g., git add more-things/food.txt), the folder will now be included in the next snapshot.

PRO-TIP: Applying a Git command to multiple files in one go

When a Git command expects a list of files or paths as a parameter (as the git add command does), these parameters are known as pathspecs — patterns that tell Git which files or directories to operate on. Pathspecs can be simple file names, directory names, or more complex patterns.

Here are some common ways to write them, shown with examples using the git add <pathspec> command:

Specify multiple files, separated by spaces:

git add f1.txt f2.txt data/lists/f3.txt # stages the specified three filesUse a glob pattern:

git add '*.txt' # stages all .txt files in the current directoryQuoting the glob pattern is recommended so your shell doesn’t expand it before Git sees it.

Use

.to indicate 'all in the current directory and subdirectories':git add . # stages all files in current directory and its subdirectoriesSpecific directory, to indicate 'this directory and its subdirectories':

git add path/to/dir # stages all files in path/to/dir and its subdirectoriesNegated pathspecs, to indicate 'except these':

git add . ':!*.log' # stage everything except .log files

Git supports combining these features — for example, you could add all .txt files except those in a certain folder using:

git add '*.txt' ':!docs/*.txt'

Saving a Snapshot

After staging, you can now proceed to save the snapshot, aka creating a commit.

Saving a snapshot is called committing and a saved snapshot is called a commit.

A Git commit is a full snapshot of your working directory based on the files you have staged, more precisely, a record of the exact state of all files in the staging area (index) at that moment -- even the files that have not changed since the last commit. This is in contrast to other revision control software that only store the in a commit. Consequently, a Git commit has all the information it needs to recreate the snapshot of the working directory at the time the commit was created.

A commit also includes metadata such as the author, date, and an optional commit message describing the change.

A Git commit is a snapshot of all tracked files, not simply a delta of what changed since the last commit.

Assuming you have previously staged changes to the fruits.txt, go ahead and create a commit.

1 First, let us do a sanity check using the git status command.

git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: fruits.txt

2 Now, create a commit using the commit command. The -m switch is used to specify the commit message.

git commit -m "Add fruits.txt"

[master (root-commit) d5f91de] Add fruits.txt

1 file changed, 5 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 fruits.txt

3 Verify the staging area is empty using the git status command again.

git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Note how the output says nothing to commit which means the staging area is now empty.

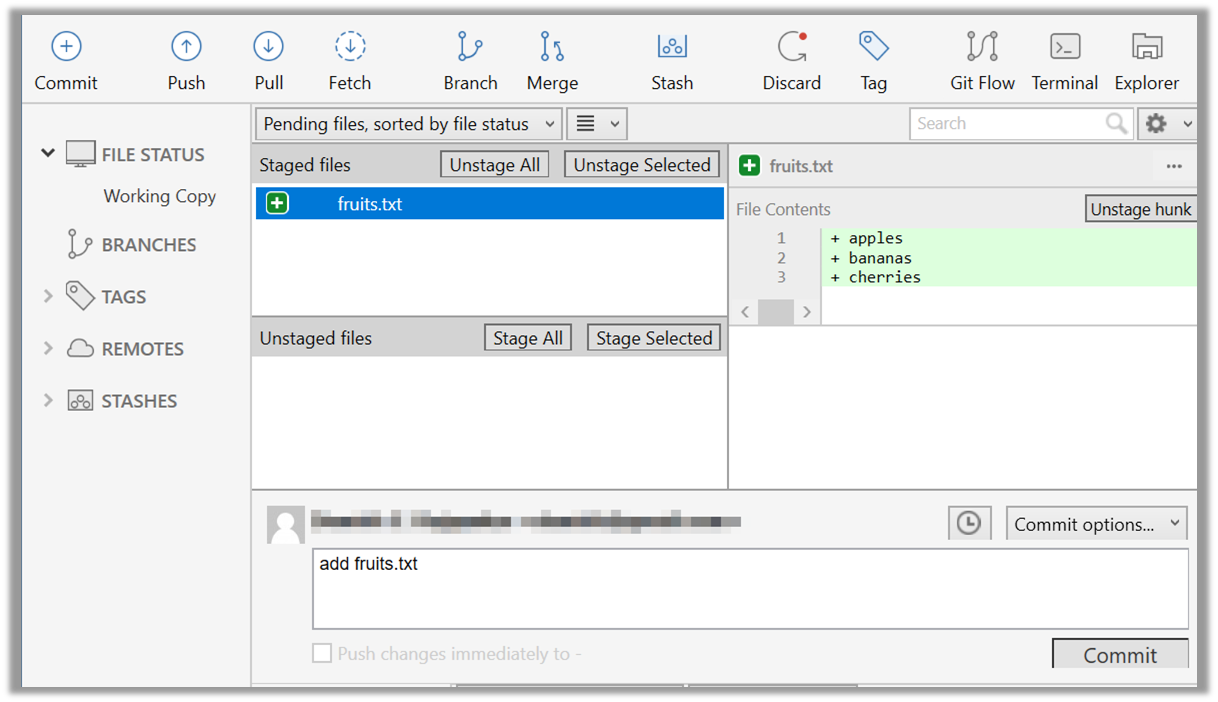

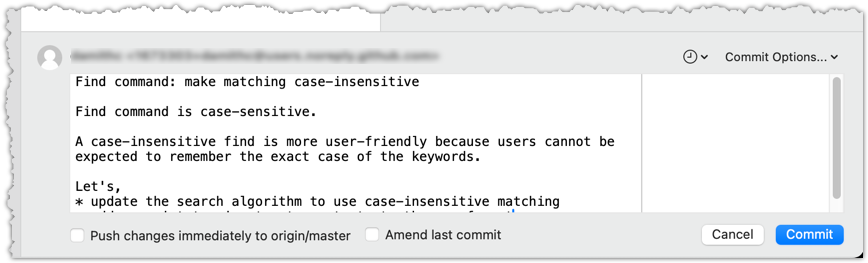

Click the Commit button, enter a commit message (e.g. add fruits.txt) into the text box, and click Commit.

done!

Examining the Revision History

It is useful to be able to visualise the commits timeline, aka the revision graph.

Git commits form a timeline, as each corresponds to a point in time when you asked Git to take a snapshot of your working directory. Each commit links to at least one previous commit, forming a structure that we can traverse.

A timeline of commits is called a branch. By default, Git names the initial branch master -- though many now use main instead. You'll learn more about branches in future lessons. For now, just be aware that the commits you create in a new repo will be on a branch called master (or main) by default.

gitGraph

%%{init: { 'theme': 'default', 'gitGraph': {'mainBranchName': 'master (or main)'}} }%%

commit id: "Add fruits.txt"

commit id: "Update fruits.txt"

commit id: "Add colours.txt"

commit id: "..."

Git can show you the list of commits in the Git history.

Preparation Use the things repo you created in a previous lesson. Alternatively, you can use the commands given below to create such a repo from scratch.

mkdir things # create a folder for the repo

cd things

git init

echo -e "apples\nbananas\ncherries\ndragon fruits" > fruits.txt

git add fruits.txt

git commit -m "Add fruits.txt"

You can copy-paste a list of commands (such as commands given above), including any comments, to the terminal. After that, hit enter to run them in sequence.

1 View the list of commits, which should show just the one commit you created just now.

You can use the git log command to see the commit history.

git log

commit ... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add fruits.txt

Use the Q key to exit the output screen of the git log command.

Note how the output has some details about the commit you just created. You can ignore most of it for now, but notice it also shows the commit message you provided.

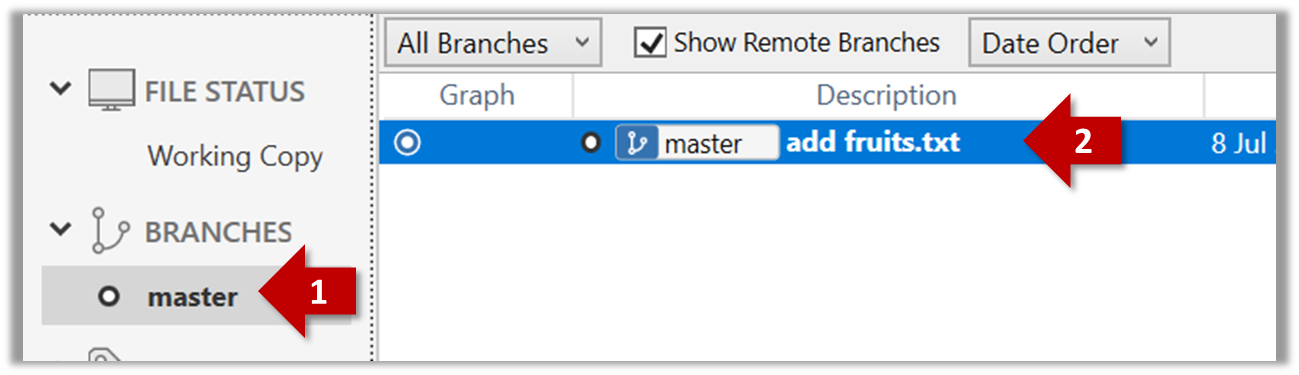

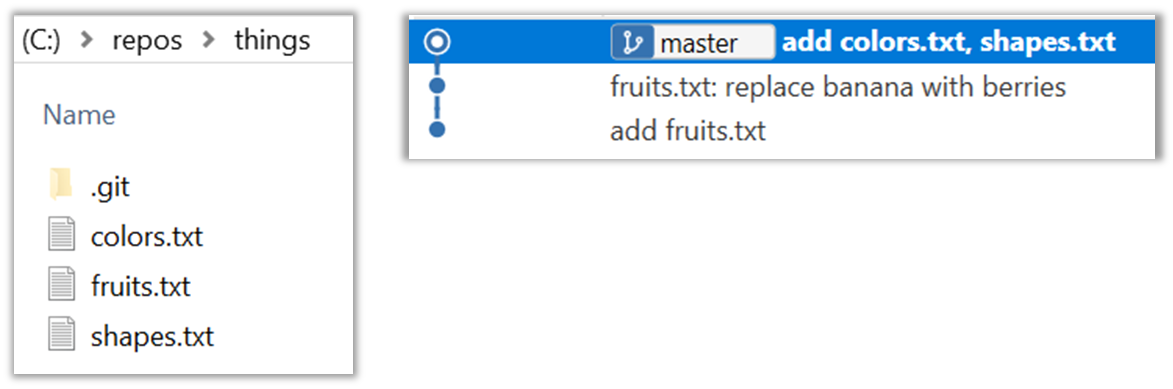

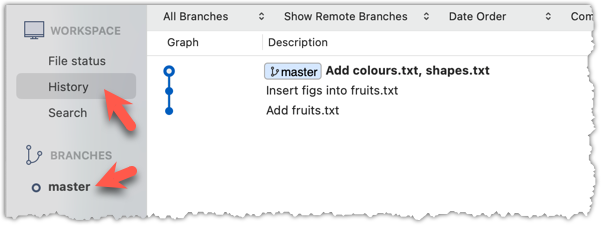

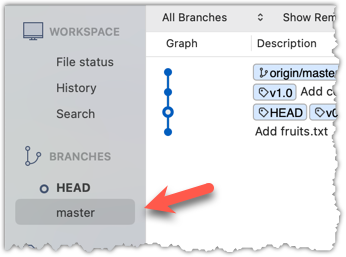

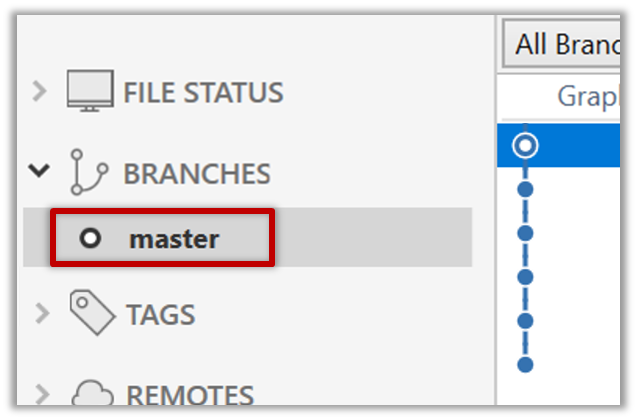

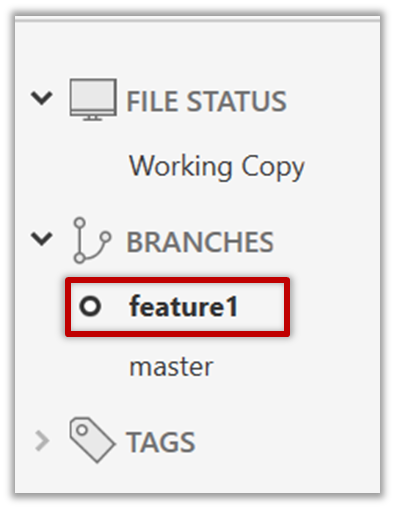

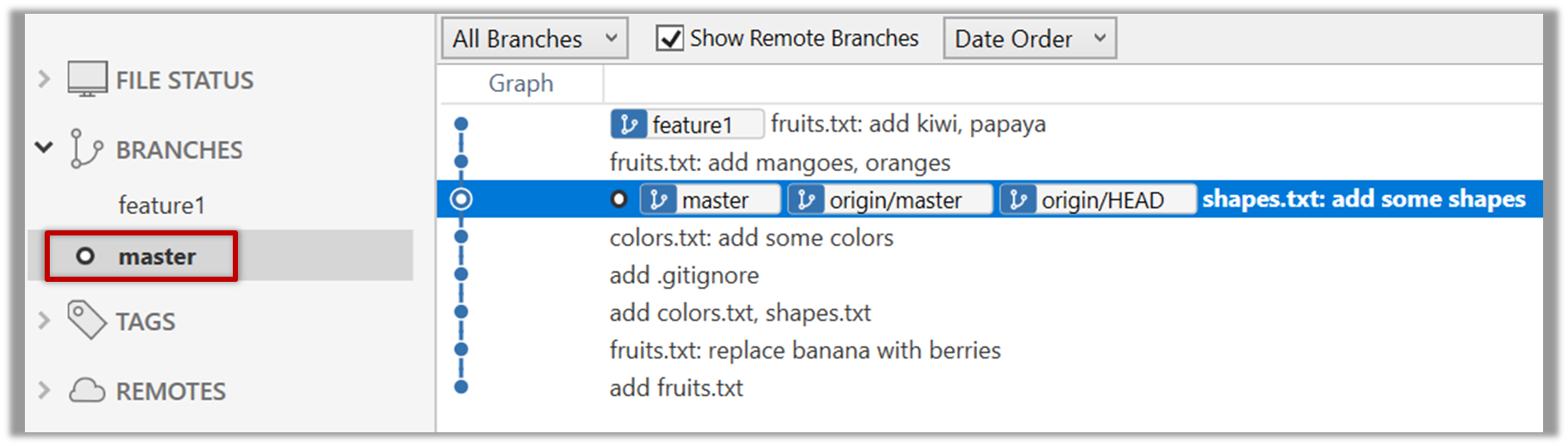

Expand the BRANCHES menu and click on the master to view the history graph, which contains only one node at the moment, representing the commit you just added. For now, ignore the label master attached to the commit.

2 Create a few more commits (i.e., a few rounds of add/edit files → stage → commit), and observe how the list of commits grows.

Here is an example list of bash commands to add two commits while observing the list of commits

echo "figs" >> fruits.txt # add another line to fruits.txt

git add fruits.txt # stage the updated file

git commit -m "Insert figs into fruits.txt" # commit the changes

git log # check commits list

echo "a file for colours" >> colours.txt # add a colours.txt file

echo "a file for shapes" >> shapes.txt # add a shapes.txt file

git add colours.txt shapes.txt # stage both files in one go

git commit -m "Add colours.txt, shapes.txt" # commit the changes

git log # check commits list

The output of the final git log should be something like this:

commit ... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

commit ...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Insert figs into fruits.txt

commit ...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add fruits.txt

SIDEBAR: Working with the 'less' pager

Some Git commands — such as git log— may show their output through a pager. A pager is a program that lets you view long text one screen at a time, so you don’t miss anything that scrolls off the top. For example, the output of git log command will temporarily hide the current content of the terminal, and enter the pager view that shows output one screen at a time. When you exit the pager, the git log output will disappear from view, and the previous content of the terminal will reappear.

command 1

output 1

git log

→

commit f761ea63738a...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add colours.txt

By default, Git uses a pager called less. Given below are some useful commands you can use inside the less pager.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

q | Quit less and return to the terminal |

↓ or j | Move down one line |

↑ or k | Move up one line |

Space | Move down one screen |

b | Move up one screen |

G | Go to the end of the content |

g | Go to the beginning of the content |

/pattern | Search forward for pattern (e.g., /fix) |

n | Repeat the last search (forward) |

N | Repeat the last search (backward) |

h | Show help screen with all less commands |

If you’d rather see the output directly, without using a pager, you can add the --no-pager flag to the command e.g.,

git --no-pager log

It is possible to ask Git to not use less at all, use a different pager, or fine-tune how less is used. For example, you can reduce Git's use of the pager (recommended), using the following command:

git config --global core.pager "less -FRX"

Explanation:

-F: Quit if the output fits on one screen (don’t show pager unnecessarily)-R: Show raw control characters (for coloured Git output)-X: Keep content visible after quitting the pager (so output stays on the terminal)

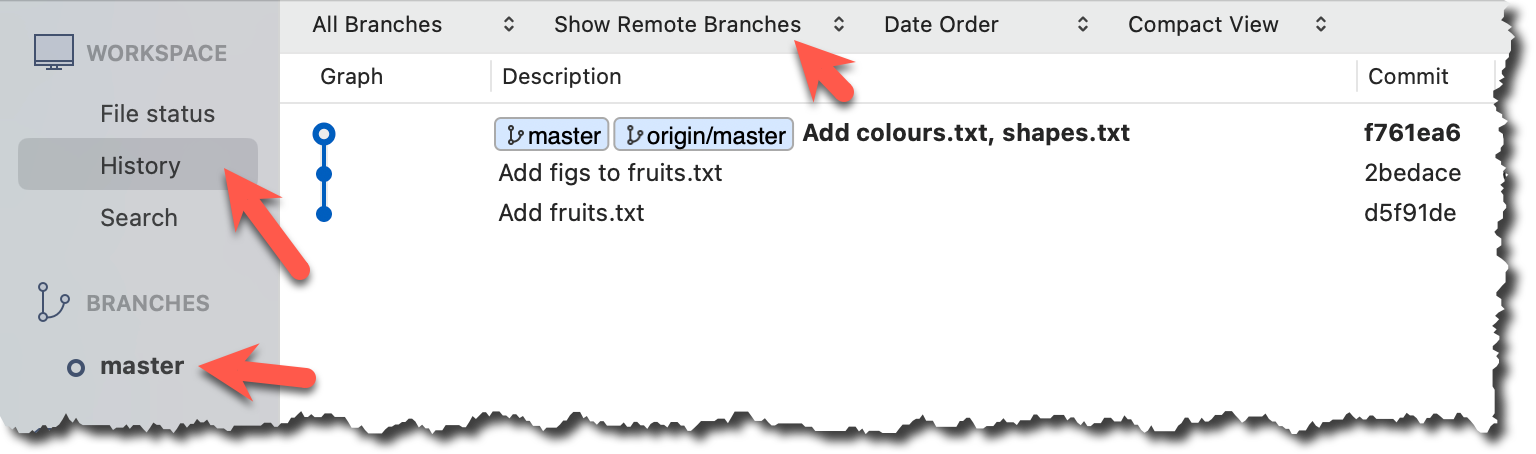

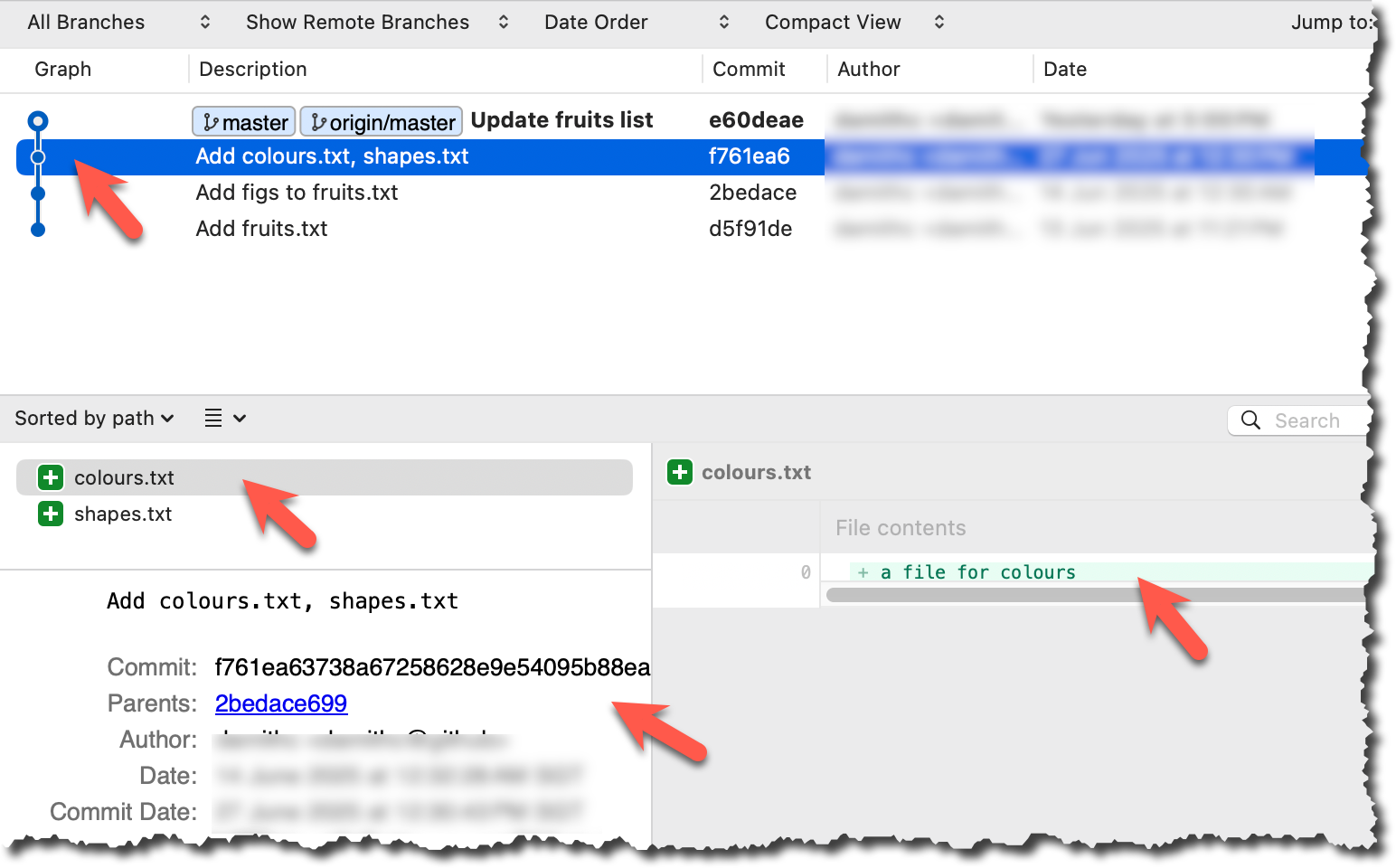

To see the list of commits, click on the History item (listed under the WORKSPACE section) on the menu on the right edge of Sourcetree.

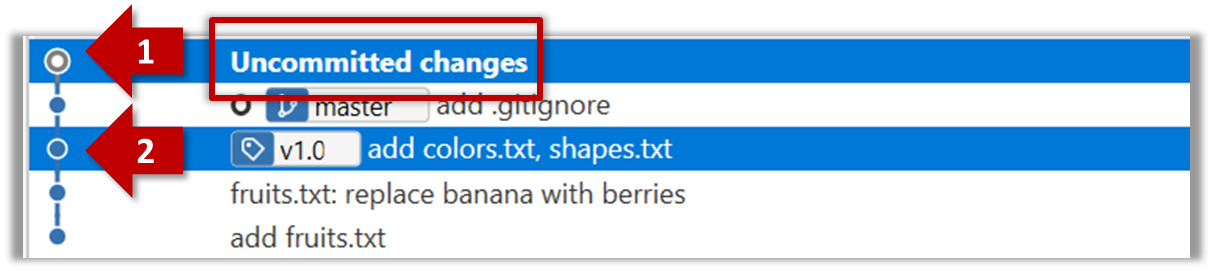

After adding two more commits, the list of commits should look something like this:

done!

The Git data model consists of two types of entities: objects and refs (short for references). In this lesson, you will encounter examples of both.

A Git revision graph is a visualisation of a repo's revision history, consisting of one or more branches. First, let us learn to work with simpler revision graphs consisting of one branch, such as the one given below.

- Nodes in the revision graph represent commits. A commit is one of four main types of Git objects. For completeness, the other three are:

- blob (short for binary large object): stores the contents of a file

- tree: represents a directory and records the hierarchy of its contents by referencing blobs and other trees

- tag (specifically, annotated tag): a label-like object that can store additional metadata and point to a specific commit

- A commit is identified by its SHA value. A SHA (Secure Hash Algorithm) value is a unique identifier generated by Git to represent each commit. It is produced by using SHA-1 (i.e., one of the algorithms in the SHA family of cryptographic hash functions) on the entire content of the commit. It's a 40-character hexadecimal string (e.g.,

f761ea63738a67258628e9e54095b88ea67d95e2) that acts like a fingerprint, ensuring that every commit can be referenced unambiguously. That is, every commit has a unique SHA-1 hash value. - A commit is a full snapshot of the working directory, constructed based on the previous commit, and the changes staged. That means each commit (except the initial commit) is based on a another 'parent' commit. Some commits can have multiple parent commits -- we’ll cover that later.

Given every commit has a unique hash, the commit hash values you see in our examples will be different from the hash values of your own commits, for example, when following our hands-on practicals.

Edges in the revision graph represent links between a commit and its parent commit(s). In some revision graph visualisations, you might see arrows (instead of lines) showing how each commit points to its parent commit.

Git uses refs to name and keep track of various points in a repository’s history. These refs are essentially 'named-pointers' that can serve as bookmarks to reach a certain point in the revision graph using the ref name.

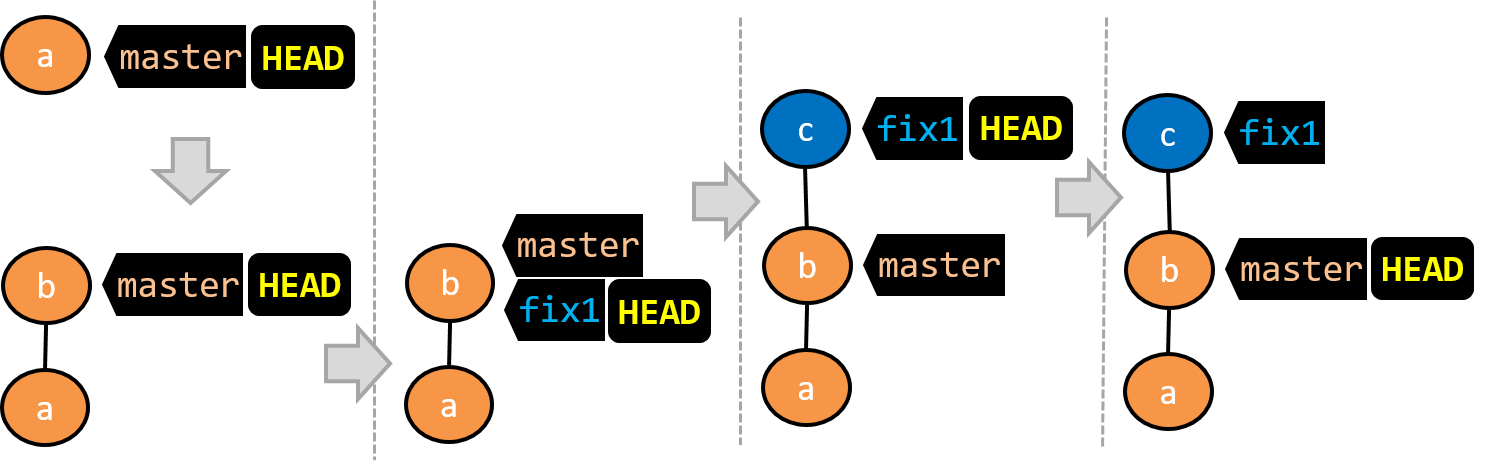

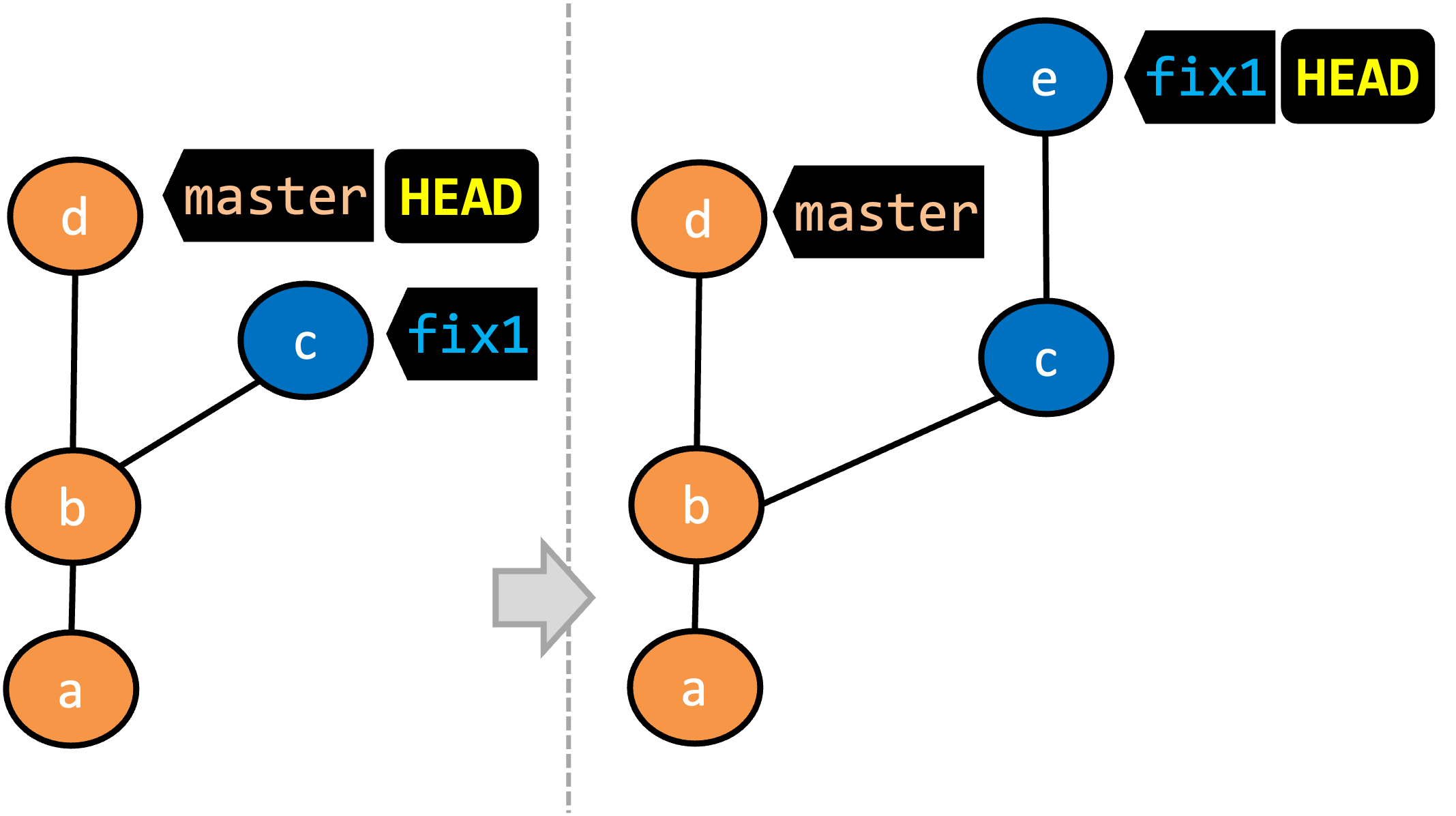

In the revision graph above, there are two refs master and ←HEAD.

- master is a branch ref. A branch ref points to the latest commit on a branch. In this visualisation, the commit shown alongside the ref is the one it points to i.e.,

C3.

When you create a new commit, the branch ref of the branch moves to the new commit. - ←HEAD is a special ref that typically points to the current branch and moves along with that branch ref. In this example, it is pointing to the

masterbranch.

In certain cases, theHEADmay point directly to a specific commit instead of a branch. This situation is called a "detachedHEAD", which will be covered in a later lesson.

Target Use Git features to examine the revision graph of a simple repo.

Preparation Use a repo with just a few commits and only one branch.

1 First, use a simple git log to view the list of commits.

git log

commit f761ea63738a... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

commit 2bedace69990...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add figs to fruits.txt

commit d5f91de5f0b5...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Fri ...

Add fruits.txt

Given below the visual representation of the same revision graph. As you can see, the log output shows the refs slightly differently, but it is not hard to see what they mean.

2 Use the --oneline flag to get a more concise view. Note how the commit SHA has been truncated to first seven characters (first seven characters of a commit SHA is enough for Git to identify a commit).

git log --oneline

f761ea6 (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

3 The --graph flag makes the result closer to a graphical revision graph. Note the * that indicates a node in a revision graph.

git log --oneline --graph

* f761ea6 (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

* 2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

* d5f91de Add fruits.txt

The --graph option is more useful when examining a more complicated revision graph consisting of multiple parallel branches.

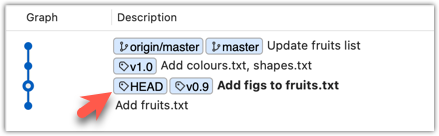

Click the History to see the revision graph.

- In some versions of Sourcetree, the

HEADref may not be shown -- it is implied that theHEADref is pointing to the same commit the currently active branch ref is pointing.

done!

Remote Repositories

To back up your Git repo on the cloud, you’ll need to use a remote repository service, such as GitHub.

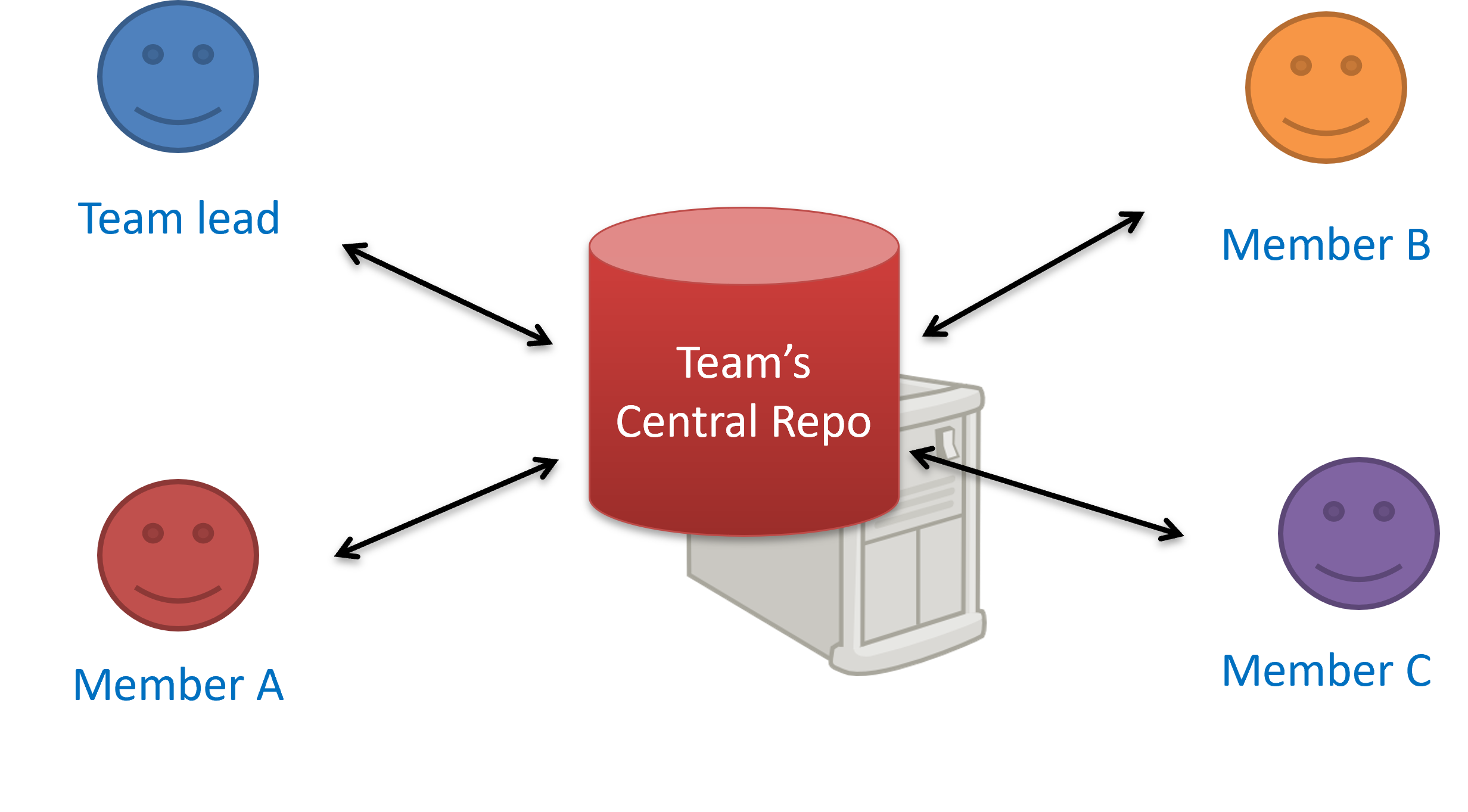

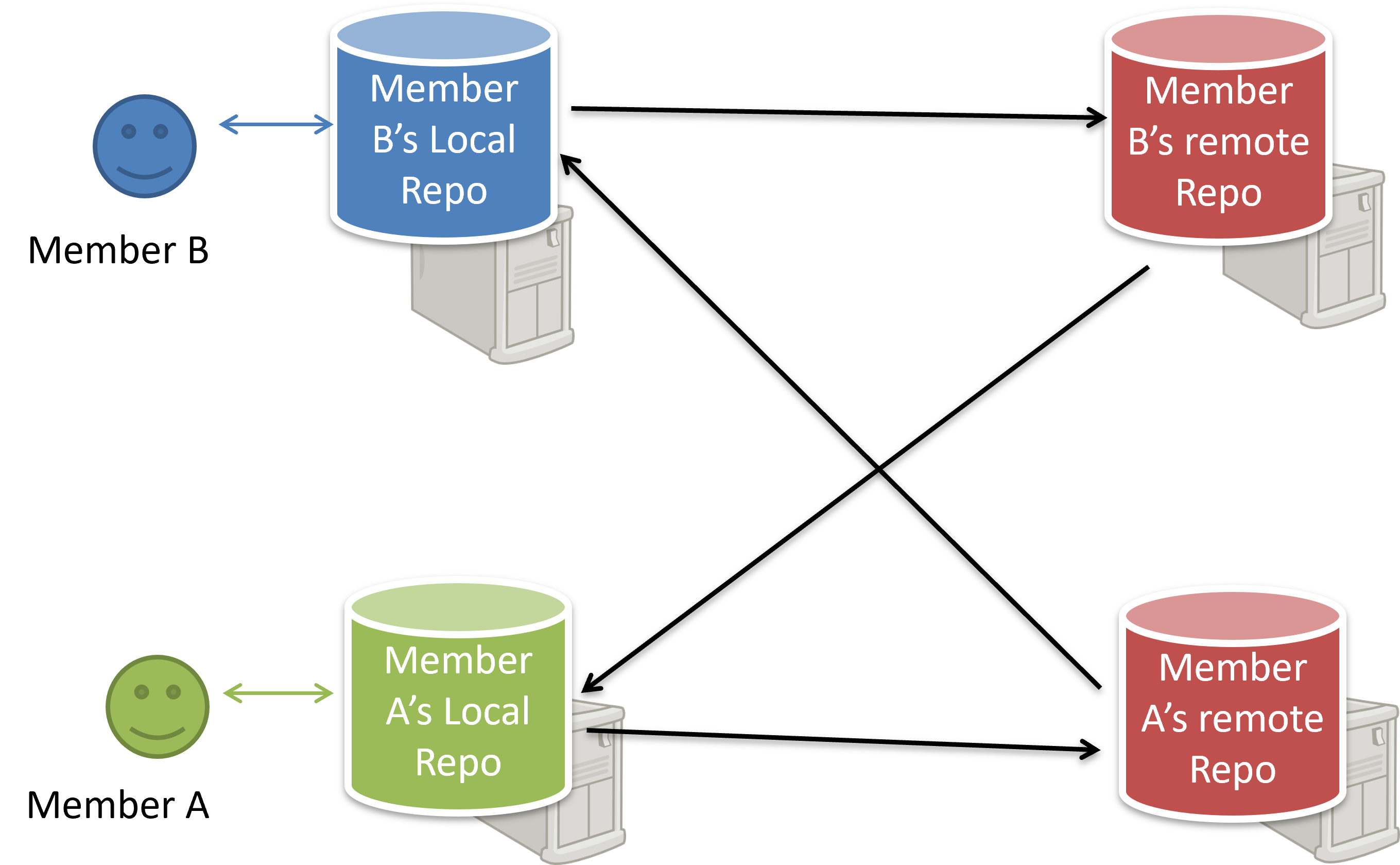

A repo you have on your computer is called a local repo. A remote repo is a repo hosted on a remote computer and allows remote access. Some use cases for remote repositories:

- as a backup of your local repo

- as an intermediary repo to work on the same files from multiple computers

- for sharing the revision history of a codebase among team members of a multi-person project

It is possible to set up a Git remote repo on your own server, but an easier option is to use a remote repo hosting service such as GitHub.

Creating a Repo on GitHub

The first step of backing up a local repo on GitHub: create an empty repository on GitHub.

You can create a remote repository based on an existing local repository, to serve as a remote copy of your local repo. For example, suppose you created a local repo and worked with it for a while, but now you want to upload it onto GitHub. The first step is to create an empty repository on GitHub.

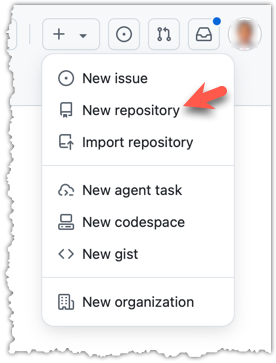

1 Login to your GitHub account and choose to create a new repo.

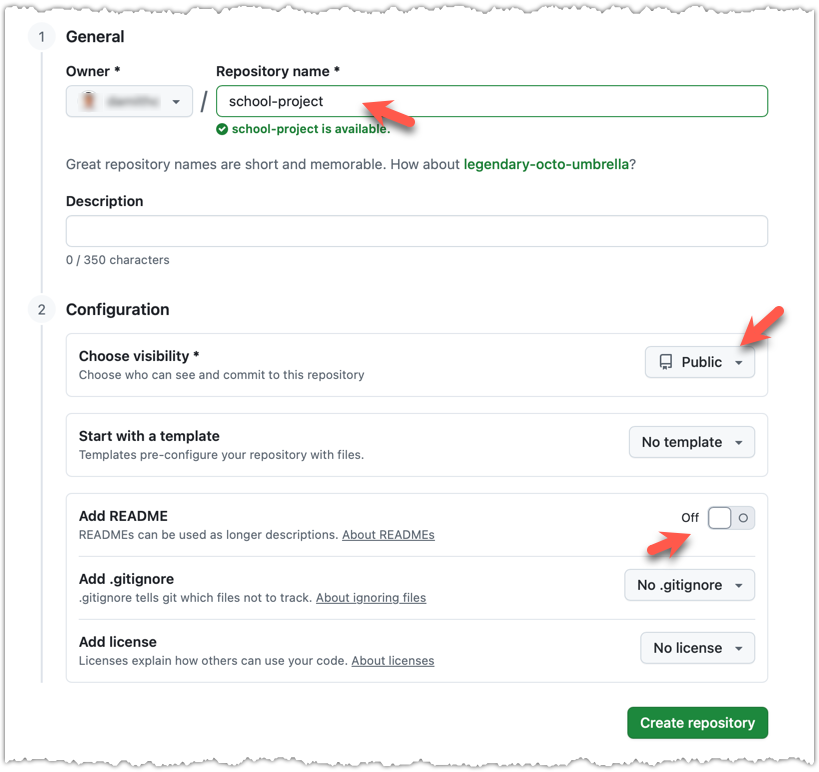

2 In the next screen, provide a name for your repo. Refer the screenshot below on some guidance on how to provide the required information.

Click Create repository button to create the new repository.

If you enable any of the three Add _____ options shown above, GitHub will not only create a repo, but will also initialise it with some initial content. That is not what we want here. To create an empty remote repo, keep those options disabled.

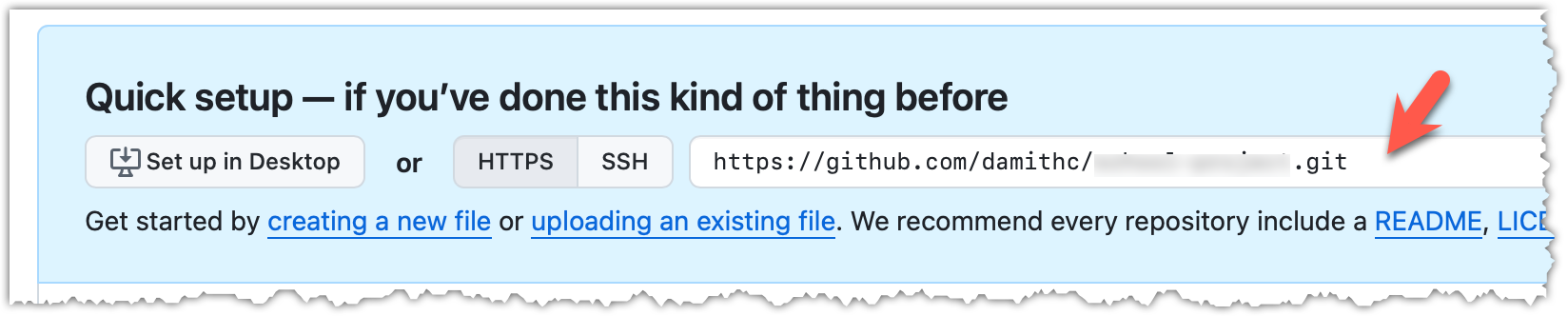

3 Note the URL of the repo. It will be of the form

https://github.com/{your_user_name}/{repo_name}.git.

e.g., https://github.com/johndoe/foobar.git (note the .git at the end)

done!

Linking a Local Repo With a Remote Repo

The second step of backing up a local repo on GitHub: link the local repo with the remote repo on GitHub.

A Git remote is a reference to a repository hosted elsewhere, usually on a server like GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket. It allows your local Git repo to communicate with another remote copy — for example, to upload locally-created commits that are missing in the remote copy.

By adding a remote, you are informing the local repo details of a remote repo it can communicate with, for example, where the repo exists and what name to use to refer to the remote.

The URL you use to connect to a remote repo depends on the protocol — HTTPS or SSH:

- HTTPS URLs use the standard web protocol and start with

https://github.com/(for GitHub users). e.g.,https://github.com/username/repo-name.git - SSH URLs use the secure shell protocol and start with

git@github.com:. e.g.,git@github.com:username/repo-name.git

A Git repo can have multiple remotes. You simply need to specify different names for each remote (e.g., upstream, central, production, other-backup ...).

Add the empty remote repo you created on GitHub as a remote of a local repo you have.

1 In a terminal, navigate to the folder containing the local repo things you created earlier.

2 List the current list of remotes using the git remote -v command, for a sanity check. No output is expected if there are no remotes yet.

3 Add a new remote repo using the git remote add <remote-name> <remote-url> command.

Format of the <remote-url>:

https://github.com/<owner>/<repo>.git # using HTTPS

git@github.com:<owner>/<repo>.git # using SSH

The full command:

git remote add origin https://github.com/JohnDoe/things.git # using HTTPS

git remote add origin git@github.com:JohnDoe/things.git # using SSH

4 List the remotes again to verify the new remote was added.

git remote -v

origin https://github.com/johndoe/things.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/johndoe/things.git (push)

The same remote will be listed twice, to show that you can do two operations (fetch and push) using this remote. You can ignore that for now. The important thing is the remote you added is being listed.

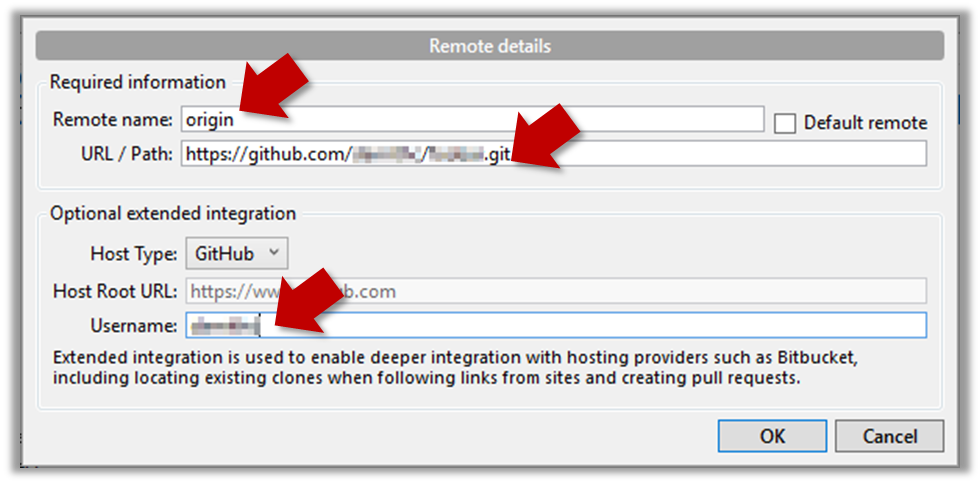

1 Open the local repo in Sourcetree.

2 Open the dialog for adding a remote, as follows:

Choose Repository → Repository Settings menu option.

Choose Repository → Repository Settings... → Choose Remotes tab.

3 Add a new remote to the repo with the following values.

Remote name: the name you want to assign to the remote repo i.e.,originURL/path: the URL of your remote repohttps://github.com/<owner>/<repo>.git # using HTTPS git@github.com:<owner>/<repo>.git # using SSHe.g.,

https://github.com/JohnDoe/things.git # using HTTPS git@github.com:JohnDoe/things.git # using SSHUsername: your GitHub username

4 Verify the remote was added by going to Repository → Repository Settings again.

5 Add another remote, to verify that a repo can have multiple remotes. You can use any name (e.g., backup and any URL for this).

done!

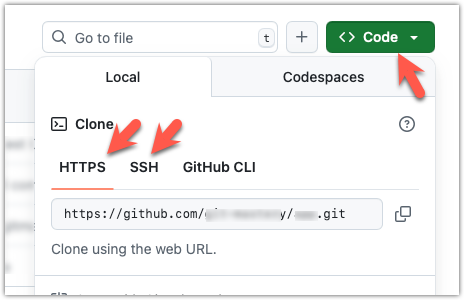

To find the URL of a repo on GitHub, you can click on the Code button:

Updating the Remote Repo

The third step of backing up a local repo on GitHub: push a copy of the local repo to the remote repo.

You can push content of one repository to another, usually from your local repo to a remote repo. Pushing transfers recorded Git history (such as past commits), but it does not transfer unstaged changes or untracked files.

- To push, you need to have to the remote repo.

- Pushing is performed one branch at a time; you must specify which branch you want to push.

You can configure Git to track a pairing between a local branch and a remote branch, so in future you can push from the same local branch to the corresponding remote branch without needing to specify them again. For example, you can set your local master branch to track the master branch on the remote repo origin i.e., local master branch will track the branch origin/master.

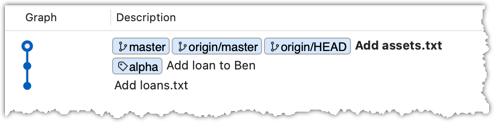

In the revision graph above, you see a new type of ref ( origin/master). This is a remote-tracking branch ref that represents the state of a corresponding branch in a remote repository (if you previously set up the branch to 'track' a remote branch). In this example, the master branch in the remote origin is also at the commit C3 (which means you have not created new commits after you pushed to the remote).

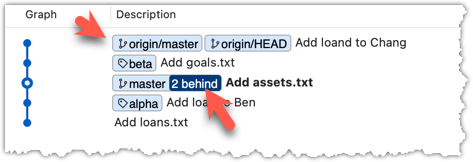

If you now create a new commit C4, the state of the revision graph will be as follows:

Explanation: When you create C4, the current branch master moves to C4, and HEAD moves along with it. However, the master branch in the remote origin remains at C3 (because you have not pushed C4 yet). That is, the remote-tracking branch origin/master is one commit behind the local branch master (or, the local branch is one commit ahead). The origin/master ref will move to C4 only after you push your local branch to the remote again.

Preparation Use a local repo that is connected to an empty remote repo e.g., the things repo from previous hands-on practicals:

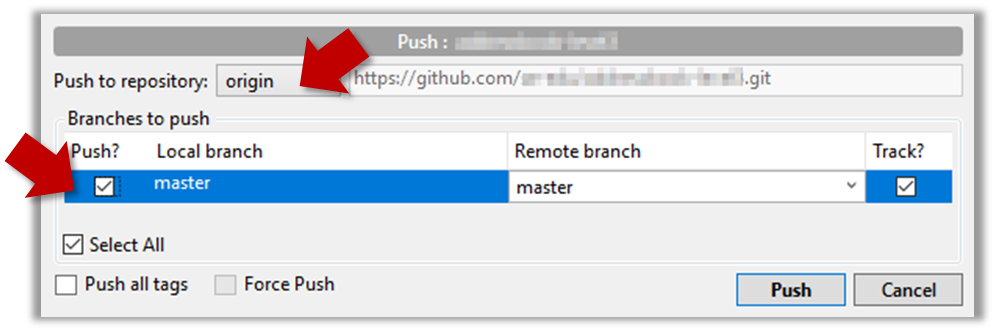

1 Push the master branch to the remote. Also instruct Git to track this branch pair.

Use the git push -u <remote-repo-name> <local-branch-name> to push the commits to a remote repository.

git push -u origin master

Explanation:

push: the Git sub-command that pushes the current local repo content to a remote repoorigin: name of the remotemaster: branch to push-u(or--set-upstream): the flag that tells Git to track that this localmasteris trackingorigin/masterbranch

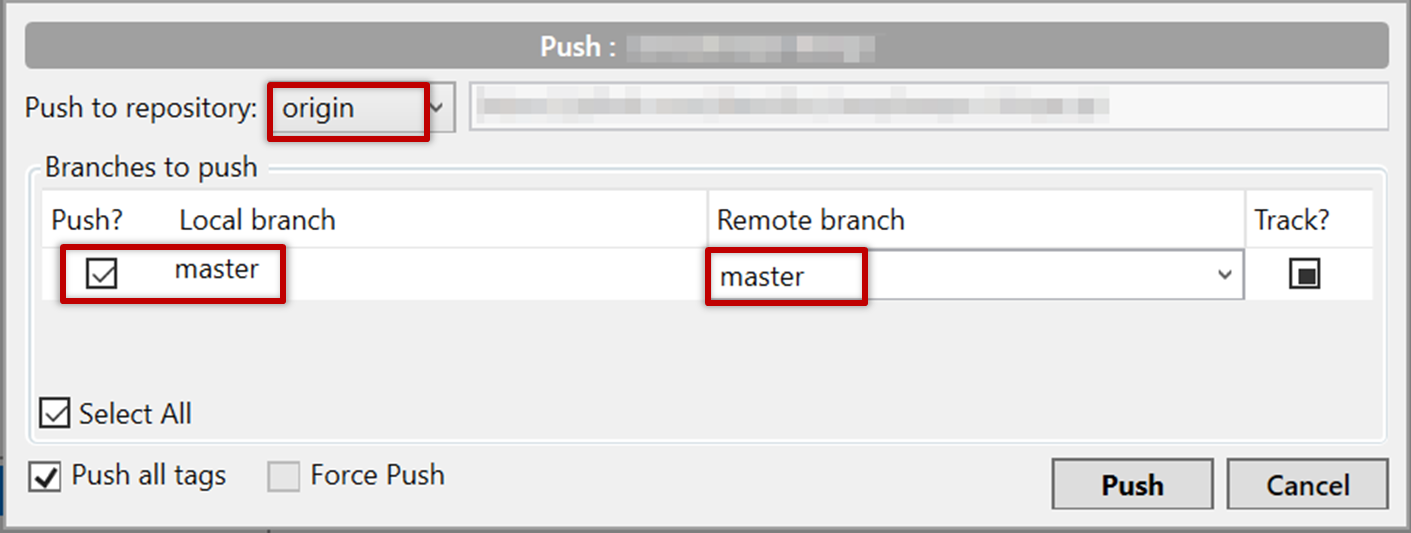

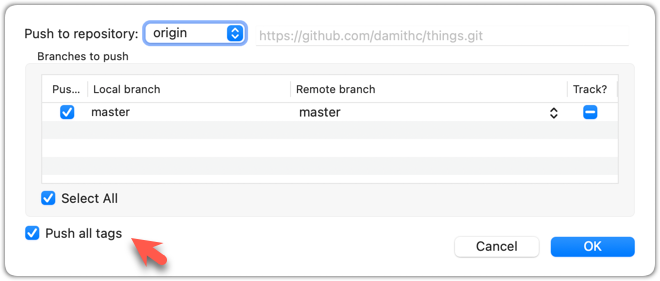

Click the Push button on the buttons ribbon at the top.

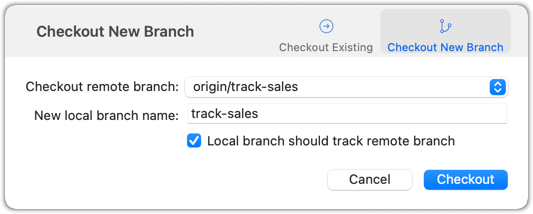

In the next dialog, ensure the settings are as follows, ensure the Track option is selected, and click the Push button on the dialog.

2 Observe the remote-tracking branch origin/master is now pointing at the same commit as the master branch.

Use the git log --oneline --graph to see the revision graph.

* f761ea6 (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

* 2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

* d5f91de Add fruits.txt

Click the History to see the revision graph.

- In some versions of Sourcetree, the

HEADref may not be shown -- it is implied that theHEADref is pointing to the same commit the currently active branch ref is pointing. - If the remote-tracking branch ref (e.g.,

origin/master) is not showing up, you may need to enable theShow Remote Branchesoption.

done!

The push command can be used repeatedly to send further updates to another repo e.g., to update the remote with commits you created since you pushed the first time.

Target Add a commit to the same local repo, and push it to the remote repo.

1 Commit some changes in your local repo. Example:

echo "Elderberries" >> fruits.txt

git commit -am "Update fruits list"

Use the git commit command to create commits, as you did before.

Optionally, you can run the git status command, which should confirm that your local branch is 'ahead' by one commit (i.e., the local branch has commits that are not present in the corresponding branch in the remote repo).

git status

On branch master

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/master' by 1 commit.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

nothing to commit, working tree clean

You can also use the git log --oneline --graph command to see where the branch refs are. Note how the remote-tracking branch origin/master is one commit behind the local master.

e60deae (HEAD -> master) Update fruits list

f761ea6 (origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

Create commits as you did before.

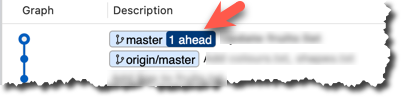

Before pushing the new commit, Sourcetree will indicate that your local branch is 'ahead' by one commit (i.e., the local branch has one new commit that is not in the corresponding branch in the remote repo).

2 Push the new commits to your fork on GitHub.

To push the newer commit(s) in the current branch master to the remote origin, you can use any of the following commands:

git push origin mastergit push origin

→ Git will assume you are pushing the current branch (e.g.,master) even if you don't specify it.git push

→ Git will assume you are pushing the current branch (e.g.,master). Due to tracking you've set up earlier, Git will assume that you want to push it to the matching branch onorigin.

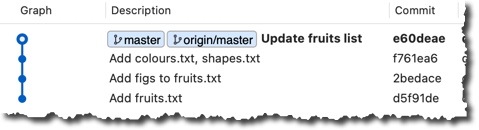

After pushing, the revision graph should look something like the following (note how both local and remote-tracking branch refs are pointing to the same commit again).

e60deae (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Update fruits list

f761ea6 Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

To push, click the Push button on the top buttons ribbon, ensure the settings are as follows in the next dialog, and click the Push button on the dialog.

After pushing the new commit to the remote, the remote-tracking branch ref should move to the new commit:

done!

Note that you can push between two repos only if those repos have a shared history among them (i.e., one should have been created by copying the other).

Omitting Files from Revision Control

Git allows you to specify which files should be omitted from revision control.

You can specify which files Git should ignore from revision control. While you can always omit files from revision control simply by not staging them, having an 'ignore-list' is more convenient, especially if there are files inside the working folder that are not suitable for revision control (e.g., temporary log files) or files you want to prevent from accidentally including in a commit (files containing confidential information).

A repo-specific ignore-list of files can be specified in a .gitignore file, stored in the root of the repo folder.

The .gitignore file itself can be either revision controlled or ignored.

- To version control it (the more common choice – which allows you to track how the

.gitignorefile changes over time), simply commit it as you would commit any other file. - To ignore it, simply add its name to the

.gitignorefile itself.

The .gitignore file supports file patterns e.g., adding temp/*.tmp to the .gitignore file prevents Git from tracking any .tmp files in the temp directory.

SIDEBAR: .gitignore File Syntax

Blank lines: Ignored and can be used for spacing.

Comments: Begin with

#(lines starting with # are ignored).# This is a commentWrite the name or pattern of files/directories to ignore.

log.txt # Ignores a file named log.txtWildcards:

*matches any number of characters, except/(i.e., for matching a string within a single directory level):abc/*.tmp # Ignores all .tmp files in abc directory**matches any number of characters (including/)**/foo.tmp # Ignores all foo.tmp files in any directory?matches a single characterconfig?.yml # Ignores config1.yml, configA.yml, etc.[abc]matches a single character (a, b, or c)file[123].txt # Ignores file1.txt, file2.txt, file3.txt

Directories:

- Add a trailing

/to match directories.logs/ # Ignores the logs directory - Patterns without

/match files/folders recursively.*.bak # Ignores all .bak files anywhere - Patterns with

/are relative to the.gitignorelocation./secret.txt # Only ignores secret.txt in the root directory

- Add a trailing

Negation: Use

!at the start of a line to not ignore something.*.log # Ignores all .log files !important.log # Except important.log

Example:

# Ignore all log files

*.log

# Ignore node_modules folder

node_modules/

# Don’t ignore main.log

!main.log

1 Add a file into your repo's working folder that you presumably do not want to revision-control e.g., a file named temp.txt. Observe how Git has detected the new file.

Add a few other files with .tmp extension.

2 Configure Git to ignore those files:

Create a file named .gitignore in the working directory root and add the text temp.txt into it.

echo "temp.txt" >> .gitignore

temp.txt

Observe how temp.txt is no longer detected as 'untracked' by running the git status command (but now it will detect the .gitignore file as 'untracked'.

Update the .gitignore file as follows:

temp.txt

*.tmp

Observe how .tmp files are no longer detected as 'untracked' by running the git status command.

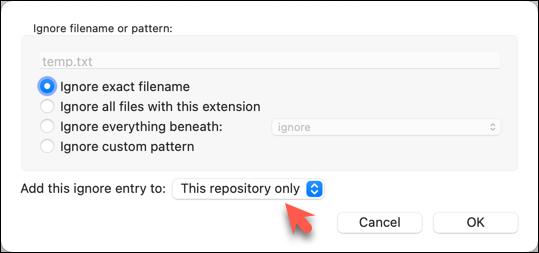

The file should be currently listed under Unstaged files. Right-click it and choose Ignore.... Choose Ignore exact filename(s) and click OK.

Also take note of other options available e.g., Ignore all files with this extension etc. They may be useful in future.

Note how the temp.text is no longer listed under Unstaged files. Observe that a file named .gitignore has been created in the working directory root and has the following line in it. This new file is now listed under Unstaged files.

temp.txt

Right-click on any of the .tmp files you added, and choose Ignore... as you did previously. This time, choose the option Ignore files with this extension.

Note how .temp files are no longer shown as unstaged files, and the .gitignore file has been updated as given below:

temp.txt

*.tmp

3 Optionally, stage and commit the .gitignore file.

done!

Files recommended to be omitted from version control

- Binary files generated when building your project e.g.,

*.class,*.jar,*.exe

Reasons:- no need to version control these files as they can be generated again from the source code

- Revision control systems are optimized for tracking text-based files, not binary files.

- Temporary files e.g., log files generated while testing the product

- Local files i.e., files specific to your own computer e.g., local settings of your IDE (

.idea/) - Sensitive content i.e., files containing sensitive/personal information e.g., credential files, personal identification data (especially if there is a possibility of those files getting leaked via the revision control system).

Duplicating a Remote Repo on the Cloud

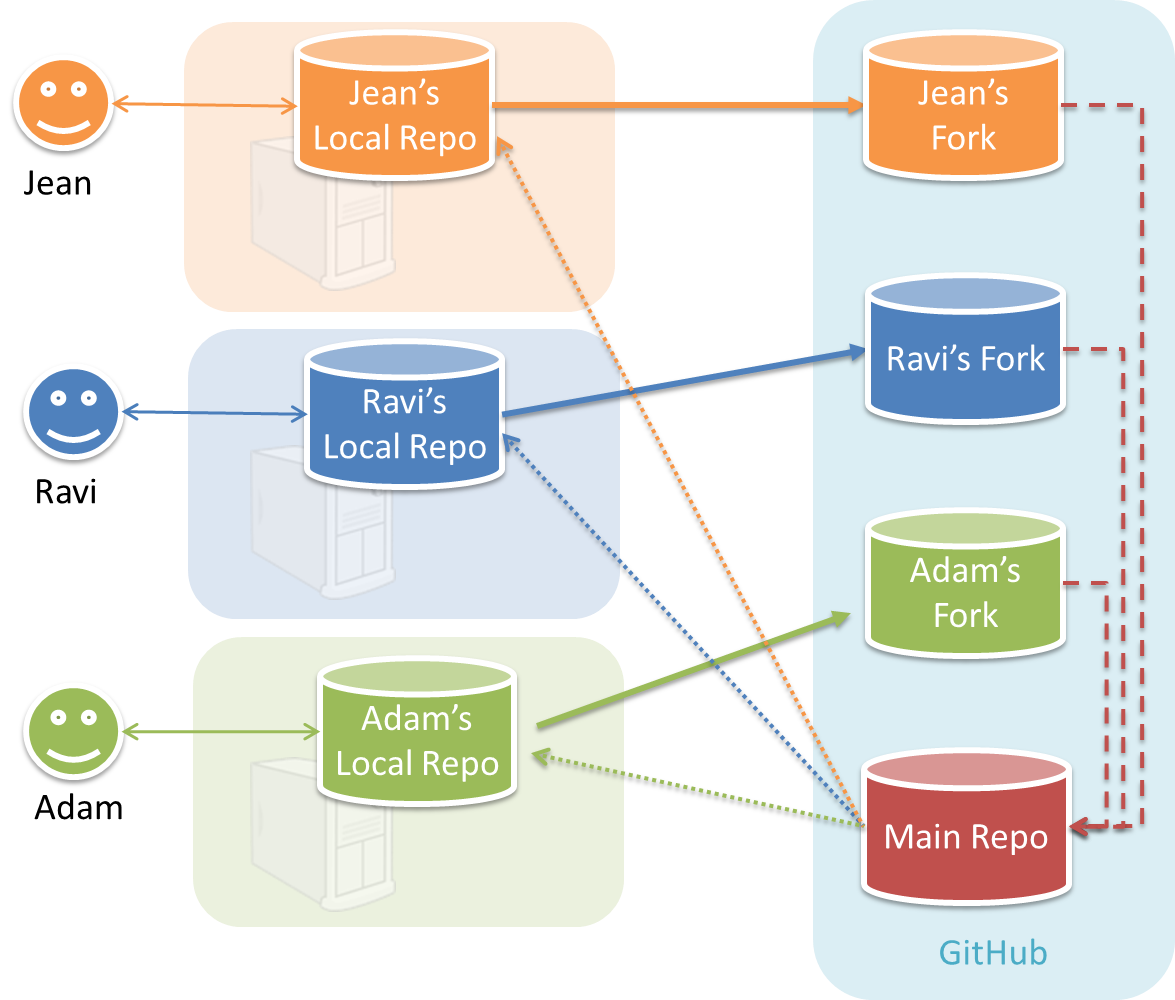

GitHub allows you to create a remote copy of another remote repo, called forking.

A fork is a copy of a remote repository created on the same hosting service such as GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket. On GitHub, you can fork a repository from another user or organisation into your own space (i.e., your user account or an organisation you have sufficient access to). Forking is particularly useful if you want to experiment with a repo but don’t have write permissions to the original -- you can fork it and work on your own remote copy without affecting the original repository.

Preparation Create a GitHub account if you don't have one yet.

1 Go to the GitHub repo you want to fork e.g., samplerepo-things

2 Click on the  button in the top-right corner. In the next step,

button in the top-right corner. In the next step,

- choose to fork to your own account or to another GitHub organization that you are an admin of.

- un-tick the

[ ] Copy the master branch onlyoption, so that you get copies of other branches (if any) in the repo.

done!

Forking is not a Git feature, but a feature provided by hosted Git services like GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket.

GitHub does not allow you to fork the same repo more than once to the same destination. If you want to re-fork, you need to delete the previous fork.

Creating a Local Copy of a Repo

The next step is to create a local copy of the remote repo, by cloning the remote repo.

You can clone a repository to create a full copy of it on your computer. This copy includes the entire revision history, branches, and files of the original, so it behaves just like the original repository. For example, you can clone a repository from a hosting service like GitHub to your computer, giving you a complete local version to work with.

Cloning a repo automatically creates a remote named origin which points to the repo you cloned from.

The repo you cloned from is often referred to as the upstream repo.

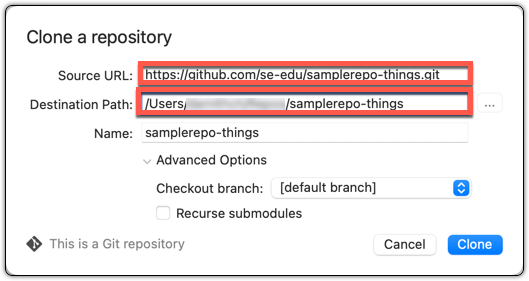

1 Clone the remote repo to your computer. For example, you can clone the samplerepo-things repo, or the fork you created from it in a previous lesson.

Note that the URL of the GitHub project is different from the URL you need to clone a repo in that GitHub project. e.g.

https://github.com/se-edu/samplerepo-things # GitHub project URL

https://github.com/se-edu/samplerepo-things.git # the repo URL

You can use the git clone <repository-url> [directory-name] command to clone a repo.

<repository-url>: The URL of the remote repository you want to copy.[directory-name](optional): The name of the folder where you want the repository to be cloned. If you omit this, Git will create a folder with the same name as the repository.

git clone https://github.com/se-edu/samplerepo-things.git # if using HTTPS

git clone git@github.com:se-edu/samplerepo-things.git # if using SSH

git clone https://github.com/foo/bar.git my-bar-copy # also specifies a dir to use

For exact steps for cloning a repo from GitHub, refer to this GitHub document.

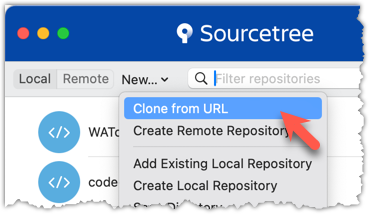

File → Clone / New ... and provide the URL of the repo and the destination directory.

File → New ... → Choose as shown below → Provide the URL of the repo and the destination directory in the next dialog.

2 Verify the clone has a remote named origin pointing to the upstream repo.

Use the git remote -v command that you learned earlier.

Choose Repository → Repository Settings menu option.

done!

Downloading Data Into a Local Repo

When there are new changes in the remote, you need to pull those changes down to your local repo.

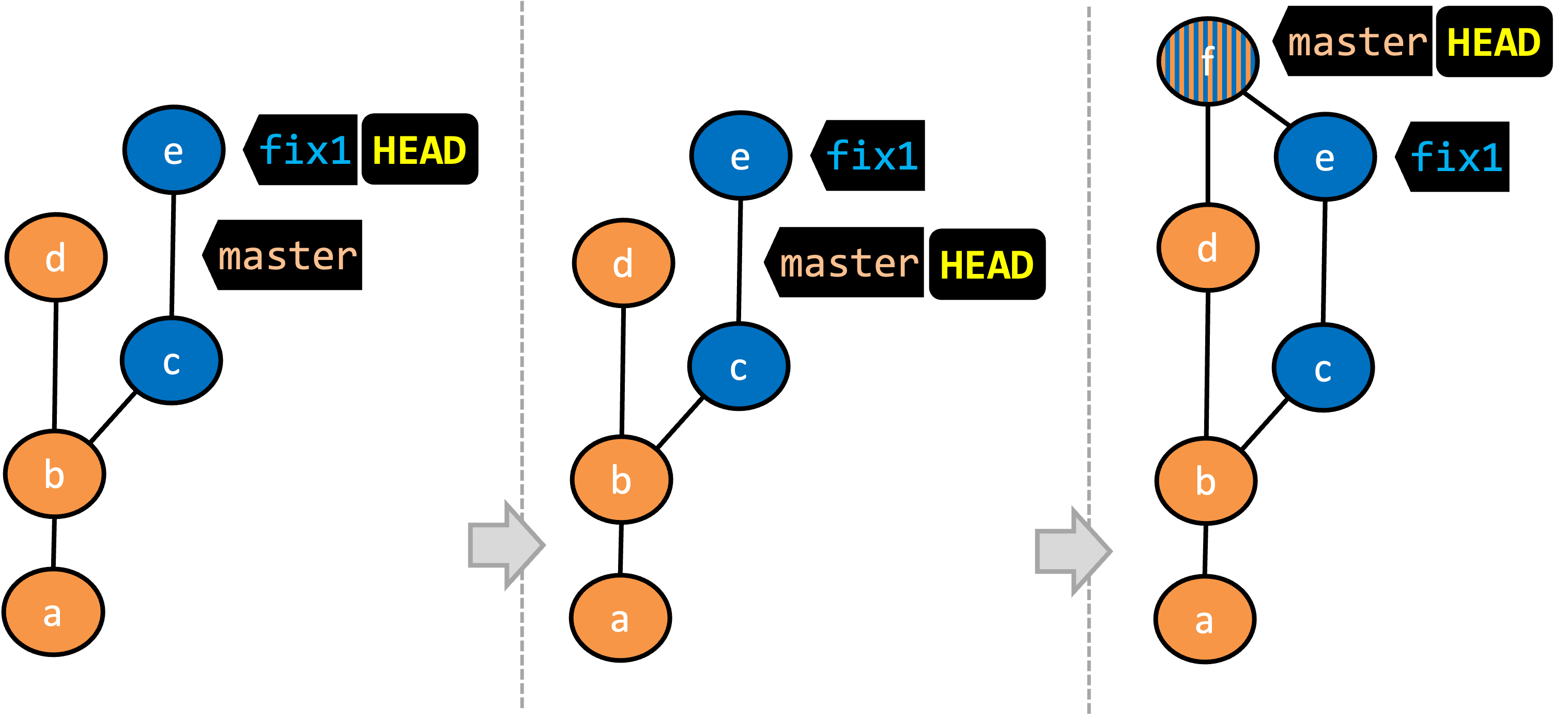

There are two steps to bringing over changes from a remote repository into a local repository: fetch and merge.

- Fetch is the act of downloading the latest changes from the remote repository, but without applying them to your current branch yet. It updates metadata in your repo so that it knows what has changed in the remote repo, but your own local branch remains untouched.

- Merge is what you do after fetching, to actually incorporate the fetched changes into your local branch. It combines your local branch with the changes from the corresponding branch from the remote repo.

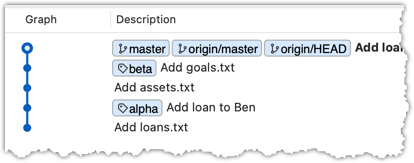

1 Clone the repo se-edu/samplerepo-finances. It has 3 commits. Your clone now has a remote origin pointing to the remote repo you cloned from.

2 Change the remote origin to point to samplerepo-finances-2. This remote repo is a copy of the one you cloned, but it has two extra commits.

git remote set-url origin https://github.com/se-edu/samplerepo-finances-2.git

Go to Repository → Repository settings ... to update remotes.

3 Verify the local repo is unaware of the extra commits in the remote.

git status

On branch master

Your branch is up to date with 'origin/master'.

nothing to commit, working tree clean

The revision graph should look like the below:

If it looks like the below, it is possible that Sourcetree is auto-fetching data from the repo periodically.

4 Fetch from the new remote.

Use the git fetch <remote> command to fetch changes from a remote. If the <remote> is not specified, the default remote origin will be used.

git fetch origin

remote: Enumerating objects: 8, done.

... # more output ...

afbe966..cc6a151 master -> origin/master

* [new tag] beta -> beta

Click on the Fetch button on the top menu:

5 Verify the fetch worked i.e., the local repo is now aware of the two missing commits. Also observe how the local branch ref of the master branch, the staging area, and the working directory remain unchanged after the fetch.

Use the git status command to confirm the repo now knows that it is behind the remote repo.

git status

On branch master

Your branch is behind 'origin/master' by 2 commits, and can be fast-forwarded.

(use "git pull" to update your local branch)

nothing to commit, working tree clean

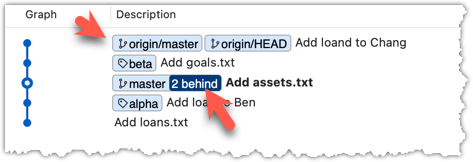

Now, the revision graph should look something like the below. Note how the origin/master ref is now two commits ahead of the master ref.

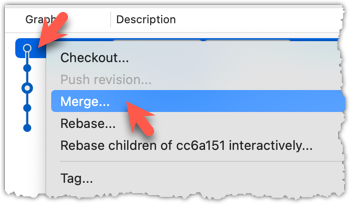

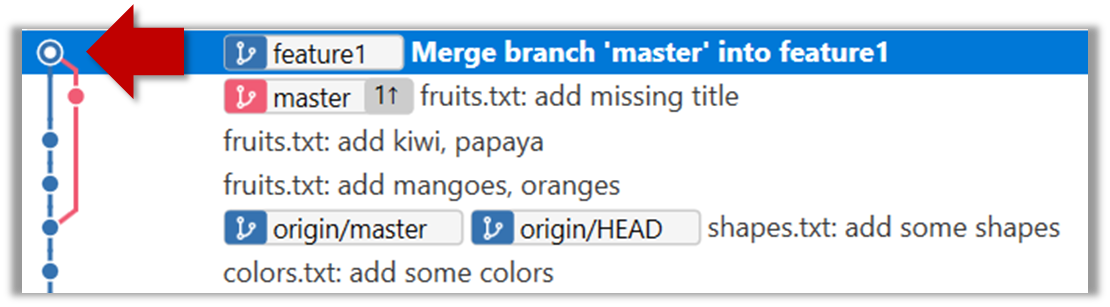

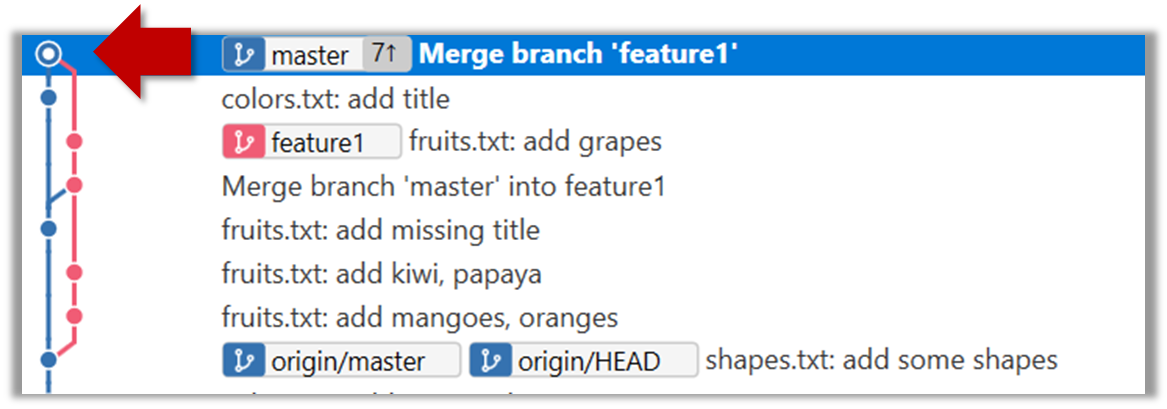

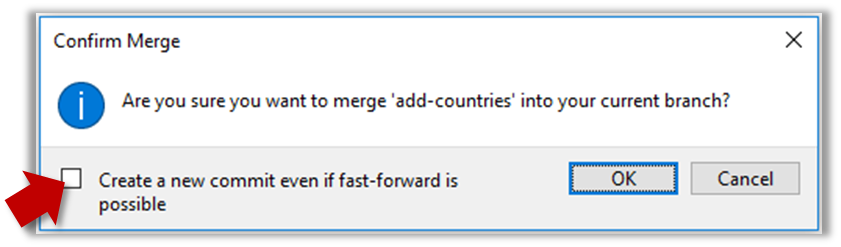

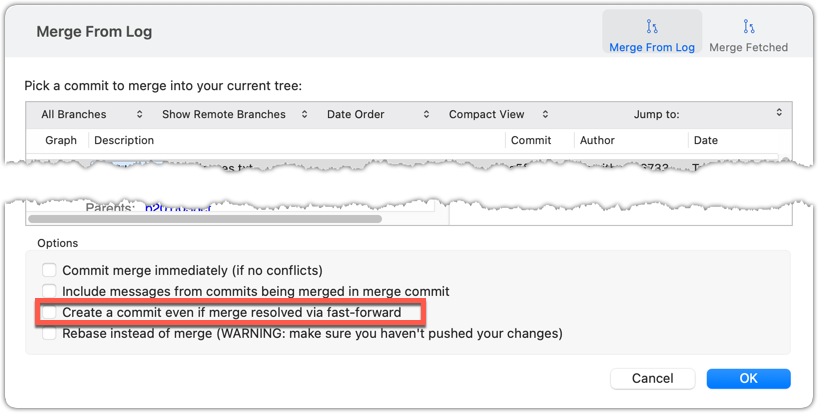

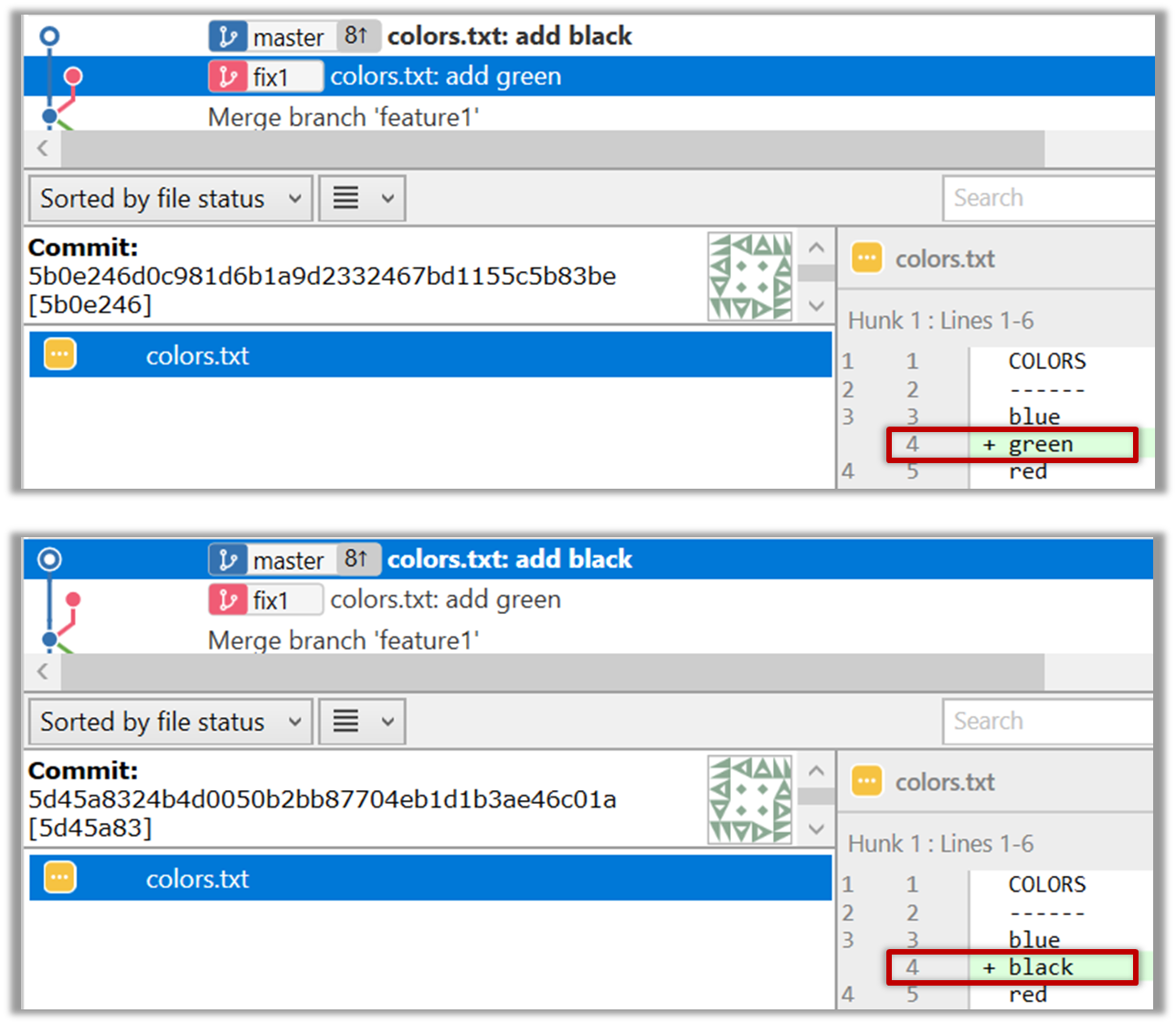

6 Merge the fetched changes.

Use the git merge <remote-tracking-branch> command to merge the fetched changes. Check the status and the revision graph to verify that the branch tip has now moved by two more commits.

git merge origin/master

git status

git log --oneline --decorate

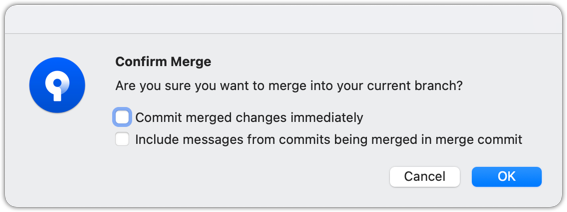

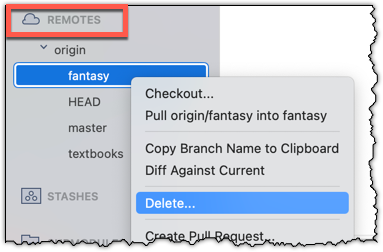

To merge the fetched changes, right-click on the latest commit on origin/remote branch and choose Merge.

In the next dialog, choose as follows:

The final result should be something like the below (same as the repo state before we started this hands-on practical):

Note that merging the fetched changes can get complicated if there are multiple branches or the commits in the local repo conflict with commits in the remote repo. We will address them when we learn more about Git branches, in a later lesson.

done!

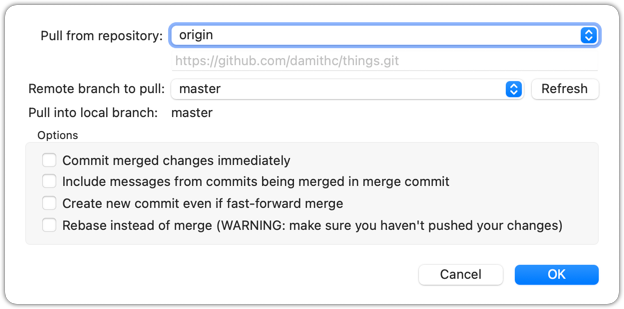

Pull is a shortcut that combines fetch and merge — it fetches the latest changes from the remote and immediately merges them into your current branch. In practice, Git users typically use the pull instead of the fetch-then-merge.

pull = fetch + merge

1 Similar to the previous hands-on practical, clone the repo se-edu/samplerepo-finances (to a new location).

Change the remote origin to point to samplerepo-finances-2.

2 Pull the newer commits from the remote, instead of a fetch-then-merge.

Use the git pull <remote> <branch> command to pull changes.

git pull origin master

The following works too. If the <remote> and <branch> are not specified, Git will pull to the current branch from the remote branch it is tracking.

git pull

Click on the Pull button on the top menu:

3 Verify the outcome is same as the fetch + merge steps you did in the previous hands-on practical.

done!

You can pull from any number of remote repos, provided the repos involved have a shared history. This can be useful when the upstream repo you forked from has some new commits that you wish to bring over to your copies of the repo (i.e., your fork and your local repo).

Preparation Fork se-edu/samplerepo-finances to your GitHub account.

Clone your fork to your computer.

Now, let's pretend that there are some new commits in upstream repo that you would like to bring over to your fork, and your local repo. Here are the steps:

1 Add the upstream repo se-edu/samplerepo-finances as remote named upstream in your local repo.

Adding remotes was covered in Lesson T2L4. Linking a Local Repo With a Remote Repo

2 Pull from the upstream repo. If there are new commits (in this case, there will be none), those will come over to your local repo. For example:

git pull upstream master

3 Push to your fork. Any new commits you pulled from the upstream repo will now appear in your fork as well. For example:

git push origin master

The method given above is the more 'standard' method of synchronising a fork with the upstream repo. In addition, platforms such as GitHub can provide other ways (example: GitHub's Sync fork feature).

4 For good measure, let's pull from another repo.

- Add the upstream repo se-edu/samplerepo-finances-2 as remote named

other-upstreamin your local repo. - Pull from it to your local repo; this will bring some new commits.

- Now, you can push those new commits to your fork.

git remote add other-upstream https://github.com/se-edu/samplerepo-finances-2.git

git pull other-upstream master

git push origin master

done!

Examining a Commit

It is useful to be able to see what changes were included in a specific commit.

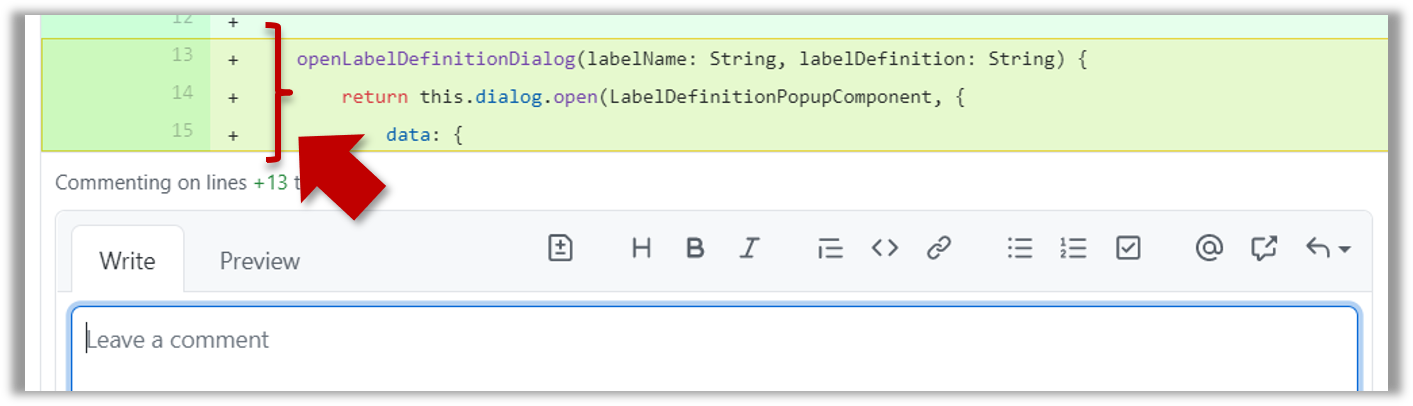

When you examine a commit, normally what you see is the 'changes made since the previous commit'. This does not mean that a Git commit contains only the changes made since the previous commit. As you recall, a Git commit contains a full snapshot of the working directory. However, tools used to examine commits typically show only the changes, as that is the more informative part.

Git shows changes included in a commit by dynamically calculating the difference between the snapshots stored in the target commit and the parent commit. This is because Git commits store snapshots of the working directory, not changes themselves.

Although each commit represents a copy of the entire working directory, Git uses space efficiently in two main ways:

- Reuse of unchanged data: If a file hasn’t changed since a previous commit, the commit simply points to the already stored version of that file instead of making another copy. This means only new or changed files take up extra space, while unchanged files are reused.

- Compression: Git also compresses all the files and data it stores using an algorithm (zlib). So, even the objects that are stored (whether reused or new) take up less disk space because they are saved in a compressed format.

To address a specific commit, you can use its SHA (e.g., e60deaeb2964bf2ebc907b7416efc890c9d4914b). In fact, just the first few characters of the SHA is enough to uniquely address a commit (e.g., e60deae), provided the partial SHA is long enough to uniquely identify the commit (i.e., only one commit has that partial SHA).

Naturally, a commit can be addressed using any ref pointing to it too (e.g., HEAD, master).

Another related technique is to use the <ref>~<n> notation (e.g., HEAD~1) to address the commit that is n commits prior to the commit pointed by <ref> i.e., "start with the commit pointed by <ref> and go back n commits".

A related alternative notation is HEAD~, HEAD~~, HEAD~~~, ... to mean HEAD~1, HEAD~2, HEAD~3 etc.

HEAD or masterHEAD~1 or master~1 or HEAD~ or master~HEAD~2 or master~2Git uses the diff format to show file changes in a commit. The diff format was originally developed for Unix. It was later extended with headers and metadata to show changes between file versions and commits. Here is an example diff showing the changes to a file.

diff --git a/fruits.txt b/fruits.txt

index 7d0a594..f84d1c9 100644

--- a/fruits.txt

+++ b/fruits.txt

@@ -1,6 +1,6 @@

-apples

+apples, apricots

bananas

cherries

dragon fruits

-elderberries

figs

@@ -20,2 +20,3 @@

oranges

+pears

raisins

diff --git a/colours.txt b/colours.txt

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..55c8449

--- /dev/null

+++ b/colours.txt

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+a file for colours

A Git diff can consist of multiple file diffs, one for each changed file. Each file diff can contain one or more hunk i.e., a localised group of changes within the file — including lines added, removed, or left unchanged (included for context).

Given below is how the above diff is divided into its components:

File diff for fruits.txt:

diff --git a/fruits.txt b/fruits.txt

index 7d0a594..f84d1c9 100644

--- a/fruits.txt

+++ b/fruits.txt

Hunk 1:

@@ -1,6 +1,6 @@

-apples

+apples, apricots

bananas

cherries

dragon fruits

-elderberries

figs

Hunk 2:

@@ -20,2 +20,3 @@

oranges

+pears

raisins

File diff for colours.txt:

diff --git a/colours.txt b/colours.txt

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..55c8449

--- /dev/null

+++ b/colours.txt

Hunk 1:

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+a file for colours

Here is an explanation of the diff:

| Part of Diff | Explanation |

|---|---|

diff --git a/fruits.txt b/fruits.txt | The diff header, indicating that it is comparing the file fruits.txt between two versions: the old (a/) and new (b/). |

index 7d0a594..f84d1c9 100644 | Shows the before and after the change, and the file mode (100 means a regular file, 644 are file permission indicators). |

--- a/fruits.txt+++ b/fruits.txt | Marks the old version of the file (a/fruits.txt) and the new version of the file (b/fruits.txt). |

| This hunk header shows that lines 1-6 (i.e., starting at line 1, showing 6 lines) in the old file were compared with lines 1–6 in the new file. |

-apples+apples, apricots | Removed line apples and added line apples, apricots. |

bananascherriesdragon fruits | Unchanged lines, shown for context. |

-elderberries | Removed line: elderberries. |

figs | Unchanged line, shown for context. |

| Hunk header showing that lines 20-21 in the old file were compared with lines 20–22 in the new file. |

oranges+pearsraisins | Unchanged line. Added line: pears.Unchanged line. |

diff --git a/colours.txt b/colours.txt | The usual diff header, indicates that Git is comparing two versions of the file colours.txt: one before and one after the change. |

new file mode 100644 | This is a new file being added. 100644 means it’s a normal, non-executable file with standard read/write permissions. |

index 0000000..55c8449 | The usual SHA hashes for the two versions of the file. 0000000 indicates the file did not exist before. |

--- /dev/null+++ b/colours.txt | Refers to the "old" version of the file (/dev/null means it didn’t exist before), and the new version. |

@@ -0,0 +1 @@ | Hunk header, saying: “0 lines in the old file were replaced with 1 line in the new file, starting at line 1.” |

+a file for colours | Added line |

Points to note:

+indicates a line being added.

-indicates a line being deleted.- Editing a line is seen as deleting the original line and adding the new line.

TargetView contents of specific commits in a repo.

Preparation You can use any repo that has commits e.g., the things repo.

1 Locate the commits to view, using the revision graph.

git log --oneline --decorate

e60deae (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Update fruits list

f761ea6 Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

2 Use the git show command to view specific commits.

git show # shows the latest commit

commit e60deaeb2964bf2ebc907b7416efc890c9d4914b (HEAD -> master, origin/master)

Author: damithc <...@...>

Date: Sat Jun ...

Update fruits list

diff --git a/fruits.txt b/fruits.txt

index 7d0a594..6d502c3 100644

--- a/fruits.txt

+++ b/fruits.txt

@@ -1,6 +1,6 @@

-apples

+apples, apricots

bananas

+blueberries

cherries

dragon fruits

-elderberries

figs

To view the parent commit of the latest commit, you can use any of these commands:

git show HEAD~1

git show master~1

git show e60deae # first few characters of the SHA

git show e60deae..... # run git log to find the full SHA and specify the full SHA

To view the commit that is two commits before the latest commit, you can use git show HEAD~2 etc.

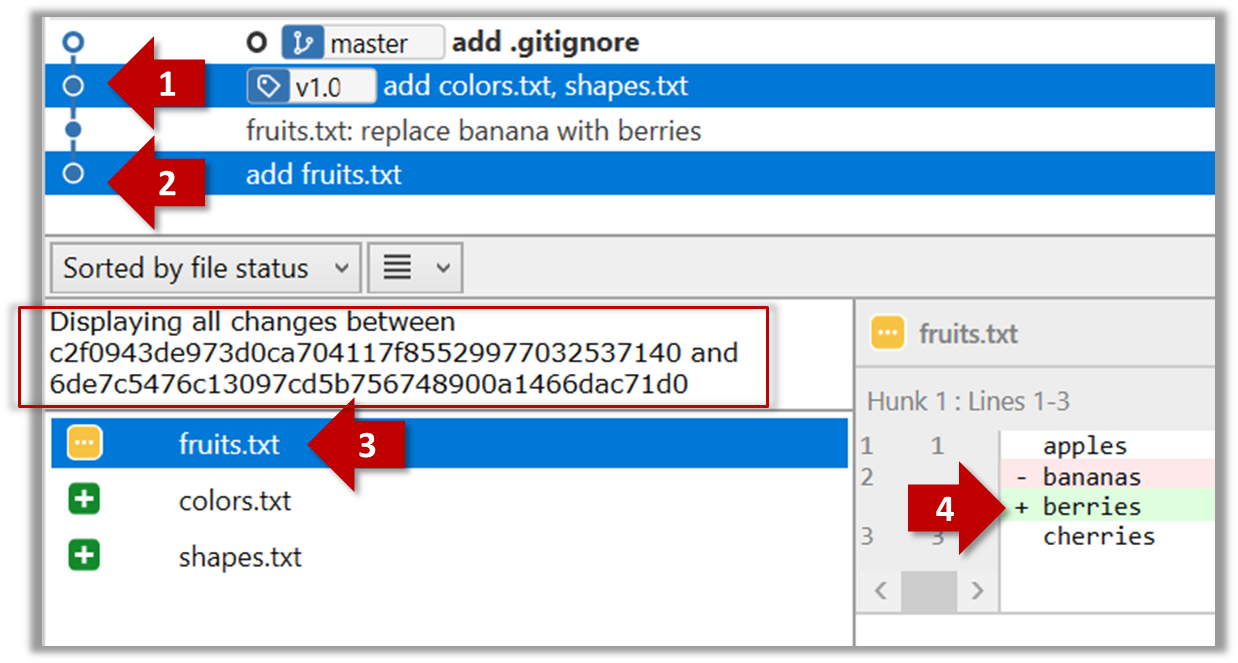

Click on the commit. The remaining panels (indicated in the image below) will be populated with the details of the commit.

done!

PRO-TIP: Use Git Aliases to Work Faster

The Git alias feature allows you to create custom shortcuts for frequently used Git commands. This saves time and reduces typing, especially for long or complex commands. Once an alias is defined, you can use the alias just like any other Git command e.g., use git lodg as an alias for git log --oneline --decorate --graph.

To define a global git alias, you can use the git config --global alias.<alias> "<command>" command. e.g.,

git config --global alias.lodg "log --oneline --graph --decorate"

You can also create shell-level aliases using your shell configuration (e.g., .bashrc, .zshrc) to make even shorter aliases. This lets you create shortcuts for any command, including Git commands, and even combine them with other tools. e.g., instead of the Git alias git lodg, you can define a shorter shell-level alias glodg.

1. Locate your .bash_profile file (likely to be in : C:\Users\<YourName>\.bash_profile -- if it doesn’t exist, create it.)

1. Locate your shell's config file e.g., .bashrc or .zshrc (likely to be in your ~ folder)

1. Locate your shell's config file e.g., .bashrc or .zshrc (likely to be in your ~ folder)

Oh-My-Zsh for Zsh terminal supports a Git plugin that adds a wide array of Git command aliases to your terminal.

2. Add aliases to that file:

alias gs='git status'

alias glod='git log --oneline --graph --decorate'

3. Apply changes by running the command source ~/.zshrc or source ~/.bash_profile or source ~/.bashrc, depending on which file you put the aliases in.

Tagging Commits

When working with many commits, it helps to tag specific commits with custom names so they’re easier to refer to later.

Git lets you tag commits with names, making them easy to reference later. This is useful when you want to mark specific commits -- such as releases or key milestones (e.g., v1.0 or v2.1). Using tags to refer to commits is much more convenient than using SHA hashes. In the diagram below, v1.0 and interim are tags.

A tag stays fixed to the commit. Unlike branch refs or HEAD, tags do not move automatically as new commits are made. As you see below, after adding a new commit, tags stay in the previous commits while master←HEAD has moved to the new commit.

Git supports two kinds of tags:

- A lightweight tag is just a ref that points directly to a commit, like a branch that doesn’t move.

- An annotated tag is a full Git object that stores a reference to a commit along with metadata such as the tagger’s name, date, and a message.

Annotated tags are generally preferred for versioning and public releases, while lightweight tags are often used for less formal purposes, such as marking a commit for your own reference.

Target Add a few tags to a repository.

Preparation Fork and clone the samplerepo-preferences. Use the cloned repo on your computer for the following steps.

1 Add a lightweight tag to the current commit as v1.0:

git tag v1.0

2 Verify the tag was added. To view tags:

git tag

v1.0

To view tags in the context of the revision graph:

git log --oneline --decorate

507bb74 (HEAD -> master, tag: v1.0, origin/master, origin/HEAD) Add donuts

de97f08 Add cake

5e6733a Add bananas

3398df7 Add food.txt

3 Use the tag to refer to the commit e.g., git show v1.0 should show the changes in the tagged commit.

4 Add an annotated tag to an earlier commit. The example below adds a tag v0.9 to the commit HEAD~2 with the message First beta release. The -a switch tells Git this is an annotated tag.

git tag -a v0.9 HEAD~2 -m "First beta release"

5 Check the new annotated tag. While both types of tags appear similarly in the revision graph, the show command on an annotated tag will show the details of the tag and the details of the commit it points to.

git show v0.9

tag v0.9

Tagger: ... <...@...>

Date: Sun Jun ...

First beta release

commit ....999087124af... (tag: v0.9)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat Jun ...

Add figs to fruits.txt

diff --git a/fruits.txt b/fruits.txt

index a8a0a01..7d0a594 100644

# rest of the diff goes here

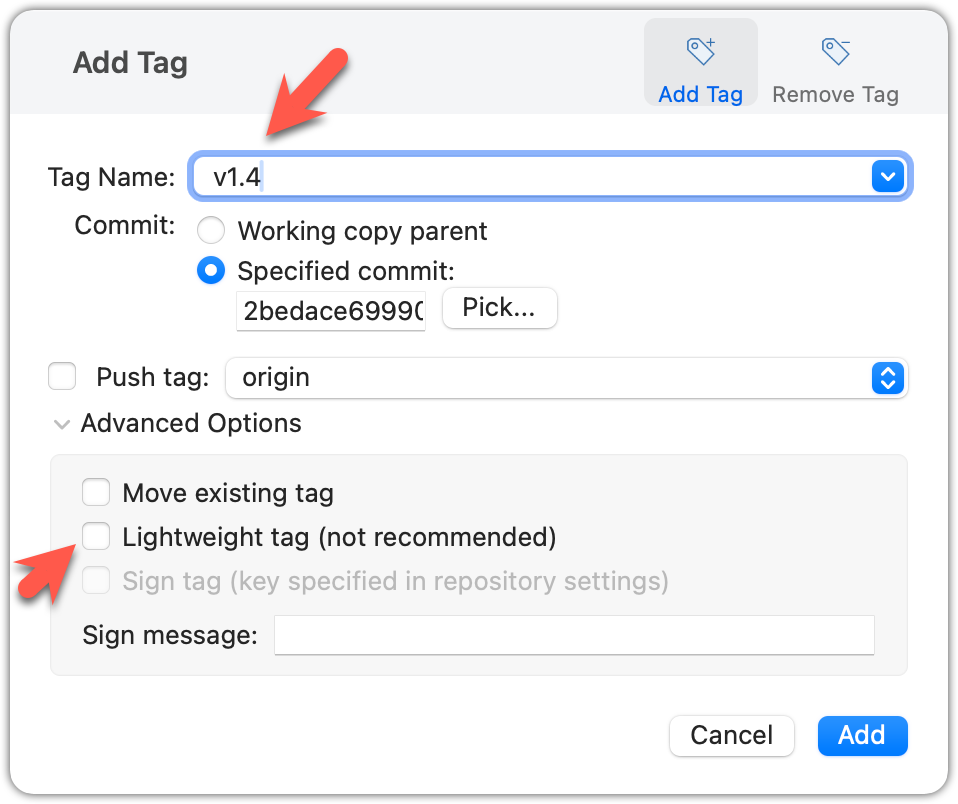

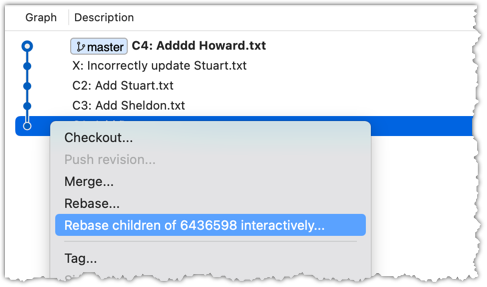

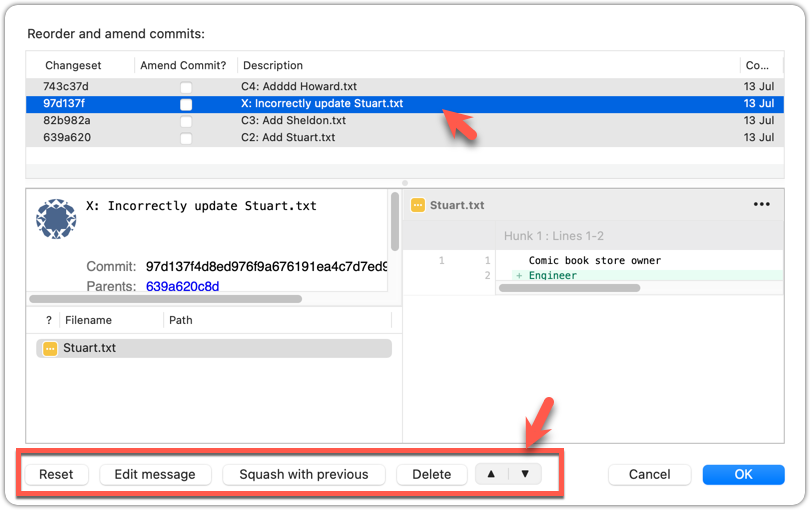

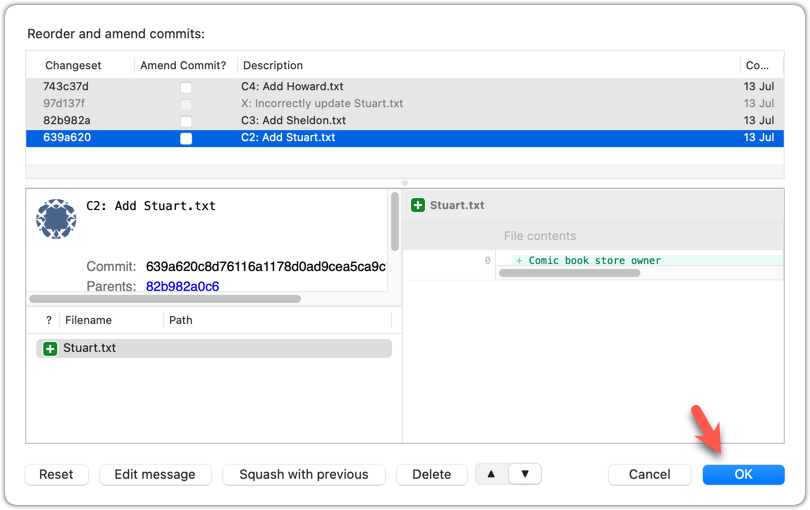

Right-click on the commit (in the graphical revision graph) you want to tag and choose Tag….

Specify the tag name e.g., v1.0 and click Add Tag.

Configure tag properties in the next dialog and press Add. For example, you can choose whether to make it a lightweight tag or an annotated tag (default).

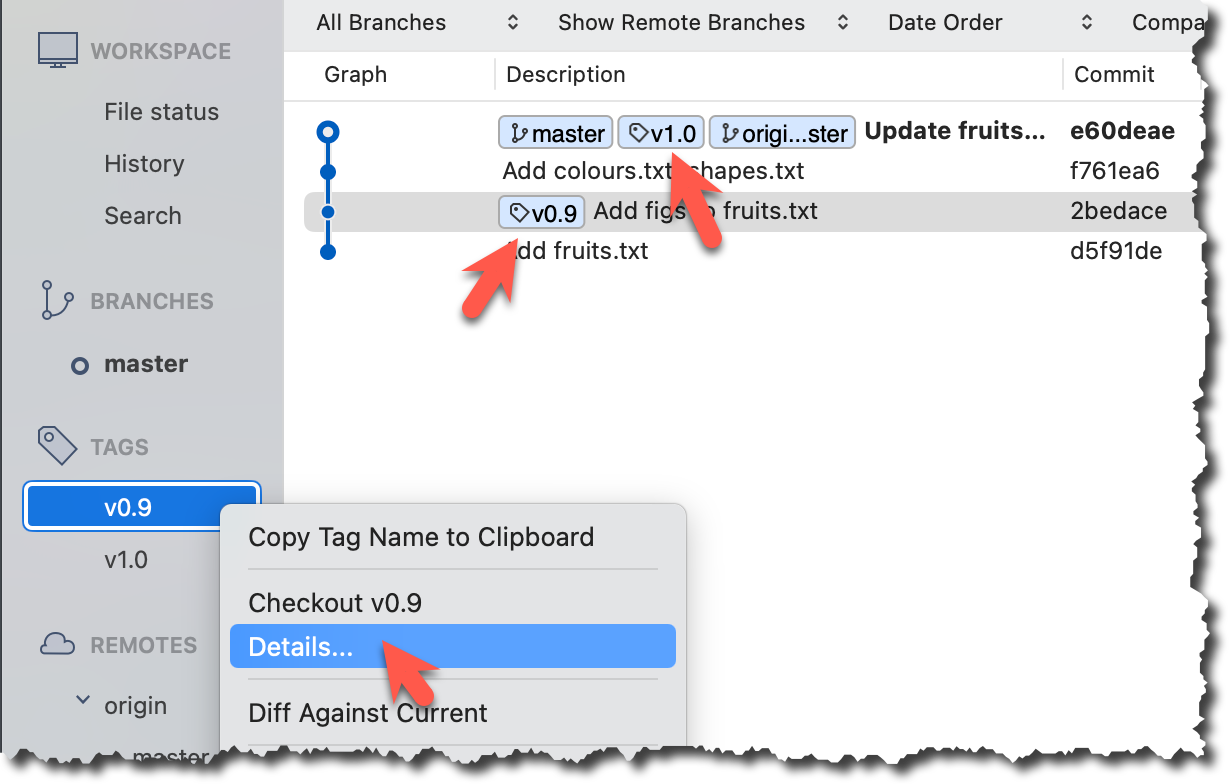

Tags will appear as labels in the revision graph, as seen below. To see the details of an annotated tag, you need to use the menu indicated in the screenshot.

done!

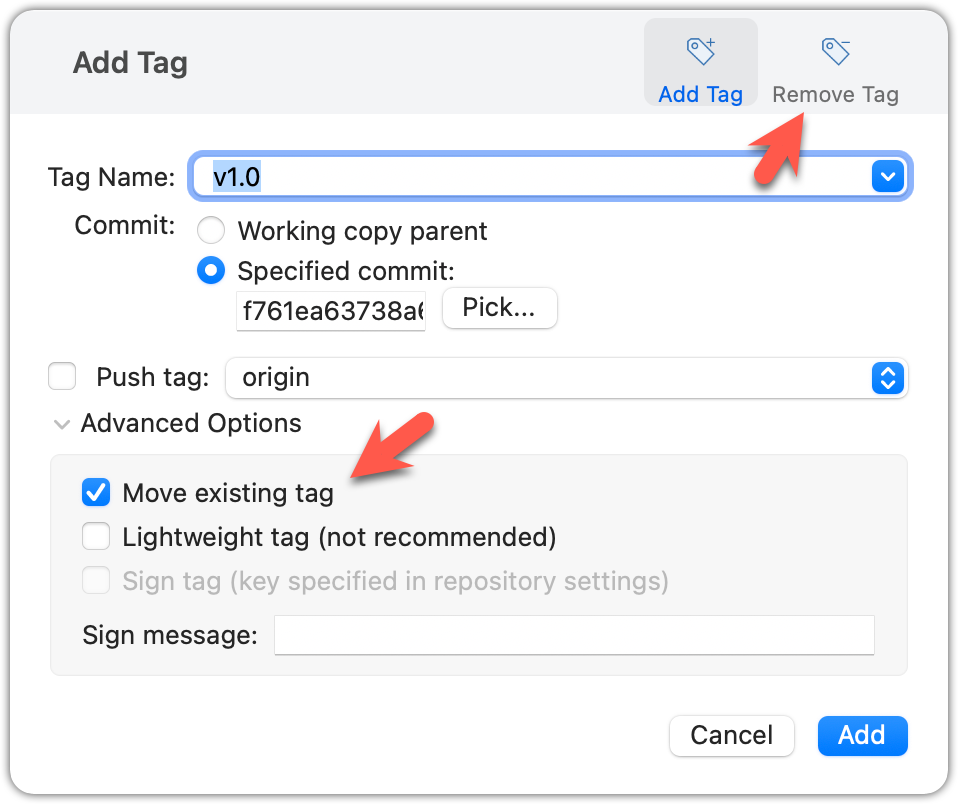

If you need to change what a tag points to, you must delete the old one and create a new tag with the same name. This is because tags are designed to be fixed references to a specific commit, and there is no built-in mechanism to 'move' a tag.

Preparation Continue with the same repo you used for the previous hands-on practical.

Move the v1.0 tag to the commit HEAD~1, by deleting it first and creating it again at the destination commit.

Delete the previous v1.0 tag by using the -d . Add it again to the other commit, as before.

git tag -d v1.0

git tag v1.0 HEAD~1

The same dialog used to add a tag can be used to delete and even move a tag. Note that the 'moving' here translates to deleting and re-adding behind the scene.

done!

Tags are different from commit messages, in purpose and in form. A commit message is a description of the commit that is part of the commit itself. A tag is a short name for a commit, which you can use to address a commit.

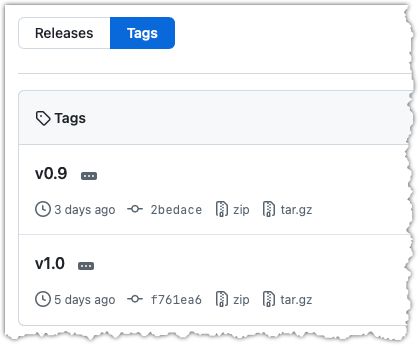

Pushing commits to a remote does not push tags automatically. You need to push tags specifically.

Target Push tags you created earlier to the remote.

Preparation Continue with the same repo you used for the previous hands-on practical.

You can go to your remote on GitHub link https://github.com/{USER}/{REPO}/tags (e.g., https://github.com/johndoe/samplerepo-preferences/tags) to verify the tag is present there.

Note how GitHub assumes these tags are meant as releases, and automatically provides zip and tar.gz archives of the repo (as at that tag).

1 Push a specific tag in the local repo to the remote (e.g., v1.0) using the git push <remote> <tag-name> command.

git push origin v1.0

In addition to verifying the tag's presence via GitHub, you can also use the following command to list the tags presently in the remote.

git ls-remote --tags origin

2 Delete a tag in the remote, using the git push --delete <remote> <tag-name> command.

git push --delete origin v1.0

3 Push all tags to the remote repo, using the git push <remote> --tags command.

git push origin --tags

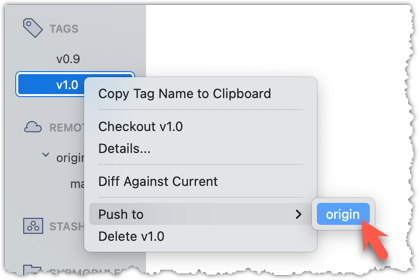

To push a specific tag, use the following menu:

To push all tags, you can tick the Push all tags option when pushing commits:

done!

Comparing Points of History

Git can tell you the net effect of changes between two points of history.

Git's diff feature can show you what changed between two points in the revision history. Given below are some use cases.

Usage 1: Examining changes in the working directory

Example use case: To verify the next commit will include exactly what you intend it to include.

Preparation For this, you can use the things repo you created earlier. If you don't have it, you can clone a copy of a similar repo given here.

1 Do some changes to the working directory. Stage some (but not all) changes. For example, you can run the following commands.

echo -e "blue\nred\ngreen" >> colours.txt

git add . # a shortcut to stage all changes

echo "no shapes added yet" >> shapes.txt

2 Examine the staged and unstaged changes.

The git diff command shows unstaged changes in the working directory (tracked files only). The output of the diff command, is a diff view (introduced in this lesson).

git diff

diff --git a/shapes.txt b/shapes.txt

index 5c2644b..949c676 100644

--- a/shapes.txt

+++ b/shapes.txt

@@ -1 +1,2 @@

a file for shapes

+no shapes added yet!

The git diff --staged command shows the staged changes (same as git diff --cached).

git diff --staged

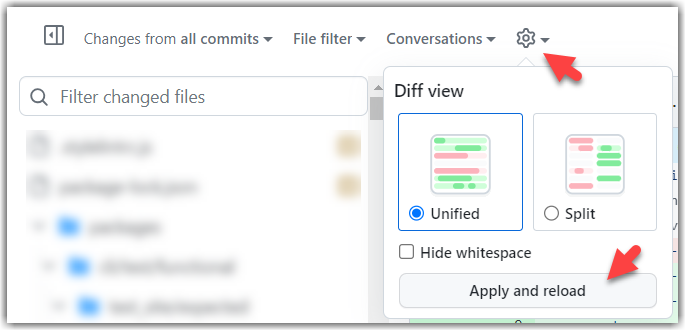

Select the two commits: Click on one commit, and Ctrl-Click (or Cmd-Click) on the second commit. The changes between the two selected commits will appear in the other panels, as shown below:

done!

Usage 2: Comparing two commits at different points of the revision graph

Example use case: Suppose you’re trying to improve the performance of a piece of software by experimenting with different code tweaks. You commit after each change (as you should). After several commits, you now want to review the overall effect of all those changes on the code.

Target Compare two commits in a repo.

Preparation You can use any repo with multiple commits e.g., the things repo.

You can use the git diff <commit1> <commit2> command for this.

- You may use any valid way to refer to commits (e.g., SHA, tag, HEAD~n etc.).

- You may also use the

..notation to specify the commit range too e.g.,0023cdd..fcd6199,HEAD~2..HEAD

git diff v0.9 HEAD

diff --git a/colours.txt b/colours.txt

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..55c8449

--- /dev/null

+++ b/colours.txt

@@ -0,0 +1 @@

+a file for colours

# rest of the diff ...

Swap the commit order in the command and see what happens.

git diff HEAD v0.9

diff --git a/colours.txt b/colours.txt

deleted file mode 100644

index 55c8449..0000000

--- a/colours.txt

+++ /dev/null

@@ -1 +0,0 @@

-a file for colours

# rest of the diff ...

As you can see, the diff is directional i.e., diff <commit1> <commit2> shows what changes you need to do to go from the <commit1> to <commit2>. If you swap <commit1> and <commit2>, the output will change accordingly e.g., lines previously shown as 'added' will now be shown as 'deleted'.

Select the two commits: Click on one commit, and Ctrl-Click (or Cmd-Click) on the second commit. The changes between the two selected commits will appear in the other panels, as shown below:

The same method can be used to compare the current state of the working directory (which might have uncommitted changes) to a point in the history.

done!

Usage 3: Examining changes to a specific file

Example use case: Similar to other use cases but when you are interested in a specific file only.

Target Examine the changes done to a file between two different points in the version history (including the working directory).

Preparation Use any repo with multiple commits e.g. the things repo.

Add the -- path/to/file to a previous diff command to narrow the output to a specific file. Some examples:

git diff -- fruits.txt # unstaged changes to fruits.txt

git diff --staged -- src/main.java # staged changes to src/main.java

git diff HEAD~2..HEAD -- fruits.txt # changes to fruits.txt between commits

Sourcetree UI shows changes to one file at a time by default; just click on the file to view changes to that file. To view changes to multiple files, Ctrl-Click (or Cmd-Click) on multiple files to select them.

done!

Traversing to a Specific Commit

Another useful feature of revision control is to be able to view the working directory as it was at a specific point in history, by checking out a commit created at that point.

Suppose you added a new feature to a software product, and while testing it, you noticed that another feature added two commits ago doesn’t handle a certain edge case correctly. Now you’re wondering: did the new feature break the old one, or was it already broken? Can you go back to the moment you committed the old feature and test it in isolation, and come back to the present after you found the answer? With Git, you can.

To view the working directory at a specific point in history, you can check out a commit created at that point.

When you check out a commit, Git:

- Updates your working directory to match the snapshot in that commit, overwriting current files as needed.

- Moves the

HEADref to that commit, marking it as the current state you’re viewing.

→

[check out commit C2...]

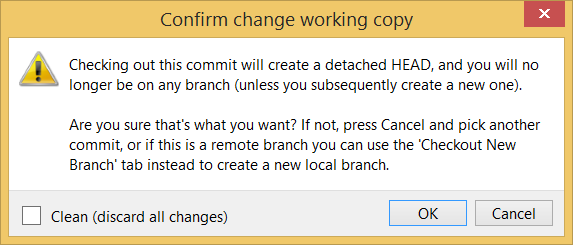

Checking out a specific commit puts you in a "detached HEAD" state: i.e., the HEAD no longer points to a branch, but directly to a commit (see the above diagram for an example). This isn't a problem by itself, but any commits you make in this state can be lost, unless certain follow-up actions are taken. It is perfectly fine to be in a detached state if you are only examining the state of the working directory at that commit.

To get out of a "detached HEAD" state, you can simply check out a branch, which "re-attaches" HEAD to the branch you checked out.

→

[check out master...]

Target Checkout a few commits in a local repo, while examining the working directory to verify that it matches the state when you created the corresponding commit

Preparation Use any repo with commits e.g., the things repo

1 Examine the revision tree, to get your bearing first.

git log --oneline --decorate

Reminder: You can use aliases to reduce typing Git commands.

e60deae (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Update fruits list

f761ea6 (tag: v1.0) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace (tag: v0.9) Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

2 Use the checkout <commit-identifier> command to check out a commit other than the one currently pointed by HEAD. You can use any of the following methods:

git checkout v1.0: checks out the commit taggedv1.0git checkout 0023cdd: checks out the commit with the hash0023cddgit checkout HEAD~2: checks out the commit 2 commits behind the most recent commit.

git checkout HEAD~2

Note: switching to 'HEAD~2'.

You are in 'detached HEAD' state.

# rest of the warning about the detached head ...

HEAD is now at 2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

3 Verify HEAD and the working directory have updated as expected.

HEADshould now be pointing at the target commit- The working directory should match the state it was in at that commit (e.g., files added after that commit -- such as

shapes.txtshould not be in the folder).

git log --oneline --decorate

2bedace (HEAD, tag: v0.9) Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

HEAD is indeed pointing at the target commit.

But note how the output does not show commits you added after the checked-out commit.

The --all switch tells git log to show commits from all refs, not just those reachable from the current HEAD. This includes commits from other branches, tags, and remotes.

git log --oneline --decorate --all

e60deae (origin/master, master) Update fruits list

f761ea6 (tag: v1.0) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace (HEAD, tag: v0.9) Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

4 Go back to the latest commit by checking out the master branch again.

git checkout master

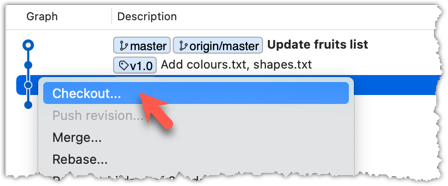

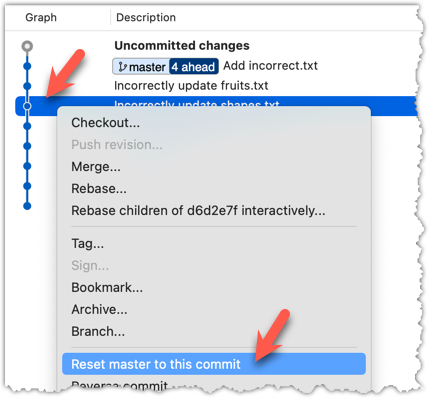

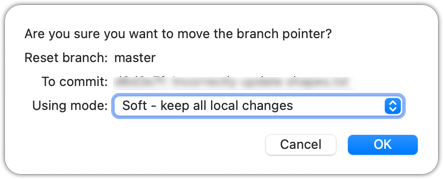

In the revision graph, double-click the commit you want to check out, or right-click on that commit and choose Checkout....

Click OK to the warning about ‘detached HEAD’ (similar to below).

The specified commit is now loaded onto the working folder, as indicated by the HEAD label.

To go back to the latest commit on the master branch, double-click the master branch.

If you check out a commit that comes before the commit in which you added a certain file (e.g., temp.txt) to the .gitignore file, and if the .gitignore file is version controlled as well, Git will now show it under ‘unstaged modifications’ because at Git hasn’t been told to ignore that file yet.

done!

If there are uncommitted changes in the working directory, Git proceeds with a checkout only if it can preserve those changes.

- Example 1: There is a new file in the working directory that is not committed yet.