Software Engineering for Self-Directed Learners CS2103/T edition - 2025 Aug-Nov

This is a printer-friendly version. It omits exercises, optional topics (i.e., four-star topics), and other extra content such as learning outcomes.

SECTION: SOFTWARE ENGINEERING

Pros and Cons

The following description of the Joys of the Programming Craft was taken (and emphasis added) from Chapter 1 of the famous book The Mythical Man-Month, by Frederick P. Brooks.

Why is programming fun? What delights may its practitioner expect as his reward?

First is the sheer joy of making things. As the child delights in his mud pie, so the adult enjoys building things, especially things of his own design. I think this delight must be an image of God's delight in making things, a delight shown in the distinctness and newness of each leaf and each snowflake.

Second is the pleasure of making things that are useful to other people. Deep within, you want others to use your work and to find it helpful. In this respect the programming system is not essentially different from the child's first clay pencil holder "for Daddy's office."

Third is the fascination of fashioning complex puzzle-like objects of interlocking moving parts and watching them work in subtle cycles, playing out the consequences of principles built in from the beginning. The programmed computer has all the fascination of the pinball machine or the jukebox mechanism, carried to the ultimate.

Fourth is the joy of always learning, which springs from the nonrepeating nature of the task. In one way or another the problem is ever new, and its solver learns something: sometimes practical, sometimes theoretical, and sometimes both.

Finally, there is the delight of working in such a tractable medium. The programmer, like the poet, works only slightly removed from pure thought-stuff. He builds his castles in the air, from air, creating by the exertion of the imagination. Few media of creation are so flexible, so easy to polish and rework, so readily capable of realizing grand conceptual structures....

Yet the program construct, unlike the poet's words, is real in the sense that it moves and works, producing visible outputs separate from the construct itself. It prints results, draws pictures, produces sounds, moves arms. The magic of myth and legend has come true in our time. One types the correct incantation on a keyboard, and a display screen comes to life, showing things that never were nor could be.

Programming then is fun because it gratifies creative longings built deep within us and delights sensibilities you have in common with all men.

Not all is delight, however, and knowing the inherent woes makes it easier to bear them when they appear.

First, one must perform perfectly. The computer resembles the magic of legend in this respect, too. If one character, one pause, of the incantation is not strictly in proper form, the magic doesn't work. Human beings are not accustomed to being perfect, and few areas of human activity demand it. Adjusting to the requirement for perfection is, I think, the most difficult part of learning to program.

Next, other people set one's objectives, provide one's resources, and furnish one's information. One rarely controls the circumstances of his work, or even its goal. In management terms, one's authority is not sufficient for his responsibility. It seems that in all fields, however, the jobs where things get done never have formal authority commensurate with responsibility. In practice, actual (as opposed to formal) authority is acquired from the very momentum of accomplishment.

The dependence upon others has a particular case that is especially painful for the system programmer. He depends upon other people's programs. These are often maldesigned, poorly implemented, incompletely delivered (no source code or test cases), and poorly documented. So he must spend hours studying and fixing things that in an ideal world would be complete, available, and usable.

The next woe is that designing grand concepts is fun; finding nitty little bugs is just work. With any creative activity come dreary hours of tedious, painstaking labor, and programming is no exception.

Next, one finds that debugging has a linear convergence, or worse, where one somehow expects a quadratic sort of approach to the end. So testing drags on and on, the last difficult bugs taking more time to find than the first.

The last woe, and sometimes the last straw, is that the product over which one has labored so long appears to be obsolete upon (or before) completion. Already colleagues and competitors are in hot pursuit of new and better ideas. Already the displacement of one's thought-child is not only conceived, but scheduled.

This always seems worse than it really is. The new and better product is generally not available when one completes his own; it is only talked about. It, too, will require months of development. The real tiger is never a match for the paper one, unless actual use is wanted. Then the virtues of reality have a satisfaction all their own.

Of course the technological base on which one builds is always advancing. As soon as one freezes a design, it becomes obsolete in terms of its concepts. But implementation of real products demands phasing and quantizing. The obsolescence of an implementation must be measured against other existing implementations, not against unrealized concepts. The challenge and the mission are to find real solutions to real problems on actual schedules with available resources.

This then is programming, both a tar pit in which many efforts have floundered and a creative activity with joys and woes all its own. For many, the joys far outweigh the woes....

SECTION: PROGRAMMING PARADIGMS

What :

Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm. A programming paradigm guides programmers to analyze programming problems, and structure programming solutions, in a specific way.

Programming languages have traditionally divided the world into two parts—data and operations on data. Data is static and immutable, except as the operations may change it. The procedures and functions that operate on data have no lasting state of their own; they’re useful only in their ability to affect data.

This division is, of course, grounded in the way computers work, so it’s not one that you can easily ignore or push aside. Like the equally pervasive distinctions between matter and energy and between nouns and verbs, it forms the background against which you work. At some point, all programmers—even object-oriented programmers—must lay out the data structures that their programs will use and define the functions that will act on the data.

With a procedural programming language like C, that’s about all there is to it. The language may offer various kinds of support for organizing data and functions, but it won’t divide the world any differently. Functions and data structures are the basic elements of design.

Object-oriented programming doesn’t so much dispute this view of the world as restructure it at a higher level. It groups operations and data into modular units called objects and lets you combine objects into structured networks to form a complete program. In an object-oriented programming language, objects and object interactions are the basic elements of design.

Some other examples of programming paradigms are:

| Paradigm | Programming Languages |

|---|---|

| Procedural Programming paradigm | C |

| Functional Programming paradigm | F#, Haskell, Scala |

| Logic Programming paradigm | Prolog |

Some programming languages support multiple paradigms.

Java is primarily an OOP language but it supports limited forms of functional programming and it can be used to (although not recommended to) write procedural code. e.g., se-edu/addressbook-level1

JavaScript and Python support functional, procedural, and OOP programming.

What :

An object in Object-Oriented Programming (OOP) has state and behavior, similar to objects in the real world.

Every object has both state (data) and behavior (operations on data). In that, they’re not much different from ordinary physical objects. It’s easy to see how a mechanical device, such as a pocket watch or a piano, embodies both state and behavior. But almost anything that’s designed to do a job does, too. Even simple things with no moving parts such as an ordinary bottle combine state (how full the bottle is, whether or not it’s open, how warm its contents are) with behavior (the ability to dispense its contents at various flow rates, to be opened or closed, to withstand high or low temperatures).

It’s this resemblance to real things that gives objects much of their power and appeal. They can not only model components of real systems, but equally as well fulfill assigned roles as components in software systems.

OOP views the world as a network of interacting objects.

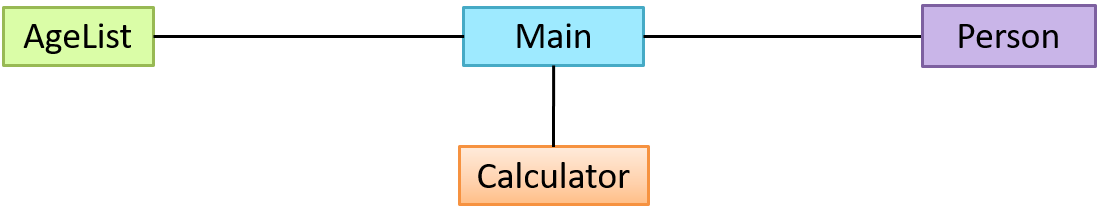

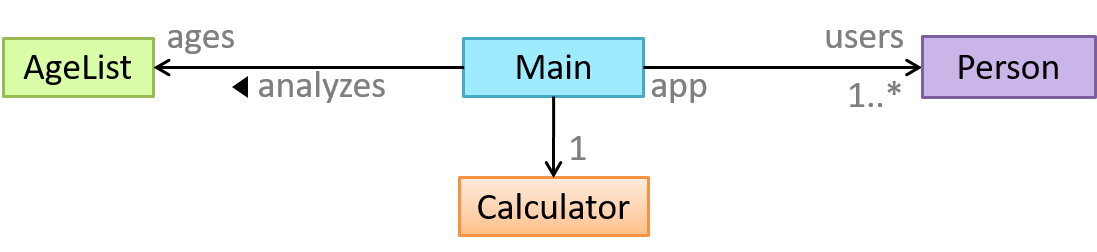

A real world scenario viewed as a network of interacting objects:

You are asked to find out the average age of a group of people Adam, Beth, Charlie, and Daisy. You take a piece of paper and pen, go to each person, ask for their age, and note it down. After collecting the age of all four, you enter it into a calculator to find the total. And then, use the same calculator to divide the total by four, to get the average age. This can be viewed as the objects You, Pen, Paper, Calculator, Adam, Beth, Charlie, and Daisy interacting to accomplish the end result of calculating the average age of the four persons. These objects can be considered as connected in a certain network of certain structure that dictates how these objects can interact. For example, You object is connected to the Pen object, and hence You can use the Pen object to write.

OOP solutions try to create a similar object network inside the computer’s memory – a sort of virtual simulation of the corresponding real world scenario – so that a similar result can be achieved programmatically.

OOP does not demand that the virtual world object network follow the real world exactly.

Our previous example can be tweaked a bit as follows:

- Use an object called

Mainto represent your role in the scenario. - As there is no physical writing involved, you can replace the

PenandPaperwith an object calledAgeListthat is able to keep a list of ages.

Every object has both state (data) and behavior (operations on data).

The state and behavior of our running example are as follows:

| Object | Real World? | Virtual World? | Example of State (i.e., Data) | Examples of Behavior (i.e., Operations) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adam | Name, Date of Birth | Calculate age based on birthday | ||

| Pen | - | Ink color, Amount of ink remaining | Write | |

| AgeList | - | Recorded ages | Give the number of entries, Accept an entry to record | |

| Calculator | Numbers already entered | Calculate the sum, divide | ||

| You/Main | Average age, Sum of ages | Use other objects to calculate |

Every object has an interface and an implementation.

Every real world object has,

- an interface through which other objects can interact with it, and,

- an implementation that supports the interface but may not be accessible to the other object.

The interface and implementation of some real-world objects in our example:

- Calculator: the buttons and the display are part of the interface; circuits are part of the implementation.

- Adam: In the context of our 'calculate average age' example,

- the interface of Adam consists of requests that Adam will respond to, e.g., "Give age to the nearest year, as at Jan 1st of this year" "State your name".

- the implementation includes the mental calculation Adam uses to calculate the age which is not visible to other objects.

Similarly, every object in the virtual world has an interface and an implementation.

The interface and implementation of some virtual-world objects in our example:

Adam: the interface might have a methodgetAge(Date asAt); the implementation of that method is not visible to other objects.

Objects interact by sending messages. Both real world and virtual world object interactions can be viewed as objects sending messages to each other. The message can result in the sender object receiving a response and/or the receiver object’s state being changed. Furthermore, the result can vary based on which object received the message, even if the message is identical (see rows 1 and 2 in the example below).

Same messages and responses from our running example:

| World | Sender | Receiver | Message | Response | State Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Real | You | Adam | "What is your name?" | "Adam" | - |

| Real | as above | Beth | as above | "Beth" | - |

| Real | You | Pen | Put nib on paper and apply pressure | Makes a mark on your paper | Ink level goes down |

| Virtual | Main | Calculator (current total is 50) | add(int i): int i = 23 | 73 | total = total + 23 |

Objects as Abstractions :

The concept of Objects in OOP is an abstraction mechanism because it allows us to abstract away the lower level details and work with bigger granularity entities i.e., ignore details of data formats and the method implementation details and work at the level of objects.

You can deal with a Person object that represents the person Adam and query the object for Adam's age instead of dealing with details such as Adam’s date of birth (DoB), in what format the DoB is stored, the algorithm used to calculate the age from the DoB, etc.

Encapsulation Of Objects :

Encapsulation protects an implementation from unintended actions and from inadvertent access.

-- Object-Oriented Programming with Objective-C, Apple

An object is an encapsulation of some data and related behavior in terms of two aspects:

1. The packaging aspect: An object packages data and related behavior together into one self-contained unit.

2. The information hiding aspect: The data in an object is hidden from the outside world and are only accessible using the object's interface.

What :

Writing an OOP program is essentially writing instructions that the computer will use to,

- create the virtual world of the object network, and

- provide it the inputs to produce the outcome you want.

A class contains instructions for creating a specific kind of objects. It turns out sometimes multiple objects keep the same type of data and have the same behavior because they are of the same kind. Instructions for creating a 'kind' (or ‘class’) of objects can be done once and those same instructions can be used to objects of that kind. We call such instructions a Class.

Classes and objects in an example scenario

Consider the example of writing an OOP program to calculate the average age of Adam, Beth, Charlie, and Daisy.

Instructions for creating objects Adam, Beth, Charlie, and Daisy will be very similar because they are all of the same kind: they all represent ‘persons’ with the same interface, the same kind of data (i.e., name, dateOfBirth, etc.), and the same kind of behavior (i.e., getAge(Date), getName(), etc.). Therefore, you can have a class called Person containing instructions on how to create Person objects and use that class to instantiate objects Adam, Beth, Charlie, and Daisy.

Similarly, you need classes AgeList, Calculator, and Main classes to instantiate one each of AgeList, Calculator, and Main objects.

| Class | Objects |

|---|---|

Person | objects representing Adam, Beth, Charlie, Daisy |

AgeList | an object to represent the age list |

Calculator | an object to do the calculations |

Main | an object to represent you (i.e., the one who manages the whole operation) |

Class Level Members :

While all objects of a class have the same attributes, each object has its own copy of the attribute value.

All Person objects have the name attribute but the value of that attribute varies between Person objects.

However, some attributes are not suitable to be maintained by individual objects. Instead, they should be maintained centrally, shared by all objects of the class. They are like ‘global variables’ but attached to a specific class. Such variables whose value is shared by all instances of a class are called class-level attributes.

The attribute totalPersons should be maintained centrally and shared by all Person objects rather than copied at each Person object.

Similarly, when a normal method is being called, a message is being sent to the receiving object and the result may depend on the receiving object.

Sending the getName() message to the Adam object results in the response "Adam" while sending the same message to the Beth object results in the response "Beth".

However, there can be methods related to a specific class but not suitable for sending messages to a specific object of that class. Such methods that are called using the class instead of a specific instance are called class-level methods.

The method getTotalPersons() is not suitable to send to a specific Person object because a specific object of the Person class should not have to know about the total number of Person objects.

Class-level attributes and methods are collectively called class-level members (also called static members sometimes because some programming languages use the keyword static to identify class-level members). They are to be accessed using the class name rather than an instance of the class.

Enumerations :

An Enumeration is a fixed set of values that can be considered as a data type. An enumeration is often useful when using a regular data type such as int or String would allow invalid values to be assigned to a variable.

Suppose you want a variable called priority to store the priority of something. There are only three priority levels: high, medium, and low. You can declare the variable priority as of type int and use only values 2, 1, and 0 to indicate the three priority levels. However, this opens the possibility of an invalid value such as 9 being assigned to it. But if you define an enumeration type called Priority that has three values HIGH, MEDIUM and LOW only, a variable of type Priority will never be assigned an invalid value because the compiler is able to catch such an error.

Priority: HIGH, MEDIUM, LOW

What

Objects in an OO solution need to be connected to each other to form a network so that they can interact with each other. Such connections between objects are called associations.

Suppose an OOP program for managing a learning management system creates an object structure to represent the related objects. In that object structure you can expect to have associations between a Course object that represents a specific course and Student objects that represent students taking that course.

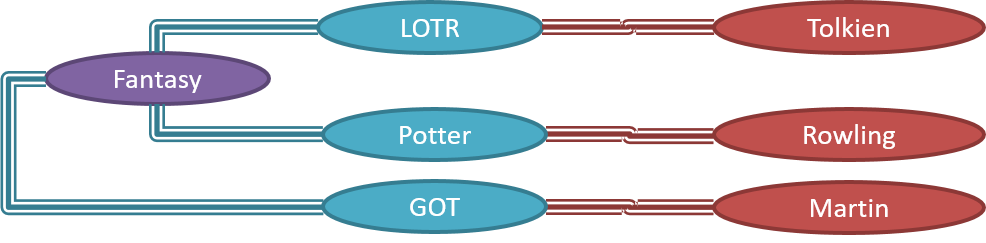

Associations in an object structure can change over time.

To continue the previous example, the associations between a Course object and Student objects can change as students enroll in the course or drop the course over time.

Associations among objects can be generalized as associations between the corresponding classes too.

In our example, as some Course objects can have associations with some Student objects, you can view it as an association between the Course class and the Student class.

Implementing associations

You use instance level variables to implement associations.

In our example, the Course class can have a students variable to keeps track of students associated with a particular course.

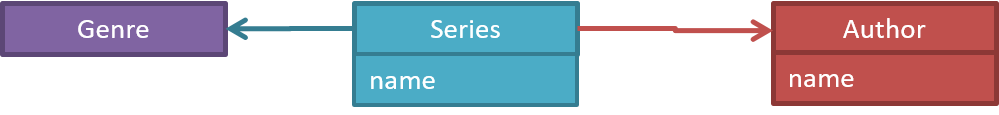

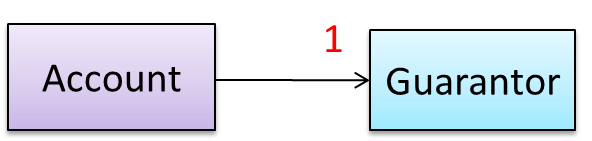

Navigability

When two classes are linked by an association, it does not necessarily mean both objects taking part in an instance of the association knows about (i.e., has a reference to) each other. The concept of navigability tells us if an object taking part in association knows about the other. In other words, it tells us if we can 'navigate' from the one object to the other in a given direction -- because if the object 'knows' about the other, it has a reference to the other object, and we can use that reference to 'navigate to' (i.e., access) that other object.

Navigability can be unidirectional or bidirectional. Suppose there is an association between the classes Box and Rope, and the Box object b and the Rope object r is taking part in one instance of that association.

- Unidirectional: If the navigability is from

BoxtoRope,bwill have a reference torbutrwill not have a reference tob. That is, one can navigate frombtorusing theb's object reference ofr(but not in the other direction).

Similarly, if the navigability is in the other direction,rwill have a reference tobbutbwill not have a reference tor. - Bidirectional:

bwill have a reference torandrwill have a reference tobi.e., the two objects will be pointing to each other for the same single instance of the association.

Note that two in opposite directions do not add up to a single bidirectional association.

In the code below, there is a bidirectional association between the Person class and the Cat class i.e., if Person p is the owner of the Cat c, p it will result in p and c having references to each other.

class Person {

Cat pet;

//...

}

class Cat{

Person owner;

//...

}

class Person:

def __init__(self):

self.pet = None # a Cat object

class Cat:

def __init__(self):

self.owner = None # a Person object

The code below has two unidirectional associations between the Person class and the Cat class (in opposite directions). Because the breeder is not necessarily the same person keeping the cat as a pet, they are two separate associations, not a bidirectional association.

class Person {

Cat pet;

//...

}

class Cat{

Person breeder;

//...

}

class Person:

def __init__(self):

self.pet = None # a Cat object

class Cat:

def __init__(self):

self.breeder = None # a Person object

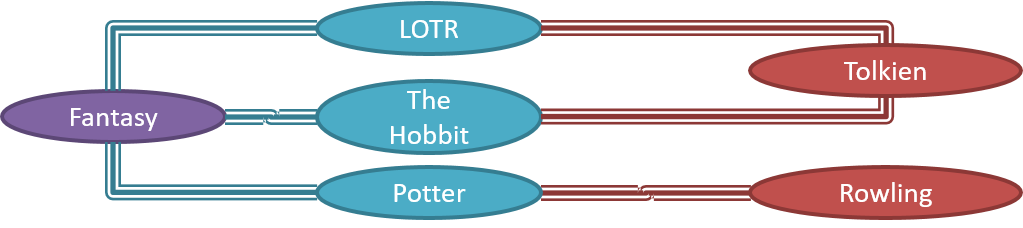

Multiplicity

Multiplicity is the aspect of an OOP solution that dictates how many objects take part in each association.

The multiplicity of the association between Course objects and Student objects tells you how many Course objects can be associated with one Student object and vice versa.

Implementing multiplicity

A normal instance-level variable gives us a 0..1 multiplicity (also called optional associations) because a variable can hold a reference to a single object or null.

In the code below, the Logic class has a variable that can hold 0..1 i.e., zero or one Minefield objects.

class Logic {

Minefield minefield;

// ...

}

class Minefield {

//...

}

class Logic:

def __init__(self):

self.minefield = None

# ...

class Minefield:

# ...

A variable can be used to implement a 1 multiplicity too (also called compulsory associations).

In the code below, the Logic class will always have a ConfigGenerator object, provided the variable is not set to null at some point.

class Logic {

ConfigGenerator cg = new ConfigGenerator();

...

}

In the Logic class, ensure there is a variable that refers to a ConfigGenerator object.

To implement other multiplicities, choose a suitable data structure such as Arrays, ArrayLists, HashMaps, Sets, etc.

This code uses a two-dimensional array to implement a 1-to-many association from the Minefield to Cell.

class Minefield {

Cell[][] cell;

//...

}

class Minefield:

def __init__(self):

self.cells = {1:[], 2:[], 3:[]}

Dependencies

In the context of OOP associations, a dependency is a need for one class to depend on another without having a direct association in the same direction. Reason for the exclusion: If there is an association from class Foo to class Bar (i.e., navigable from Foo to Bar), that means Foo is obviously dependent on Bar and hence there is no point in mentioning dependency specifically. In other words, we are specifically focusing on non-obvious dependencies here. One cause of such dependencies is interactions between objects that do not have a long-term link between them.

A Course class can have a dependency on a Registrar class because the Course class needs to refer to the Registrar class to obtain the maximum number of students it can support (e.g., Registrar.MAX_COURSE_CAPACITY).

In the code below, Foo has a dependency on Bar but it is not an association because it is only a interaction and there is no long term relationship between a Foo object and a Bar object. i.e., the Foo object does not keep the Bar object it receives as a parameter.

class Foo {

int calculate(Bar bar) {

return bar.getValue();

}

}

class Bar {

int value;

int getValue() {

return value;

}

}

class Foo:

def calculate(self, bar):

return bar.value;

class Bar:

def __init__(self, value):

self.value = value

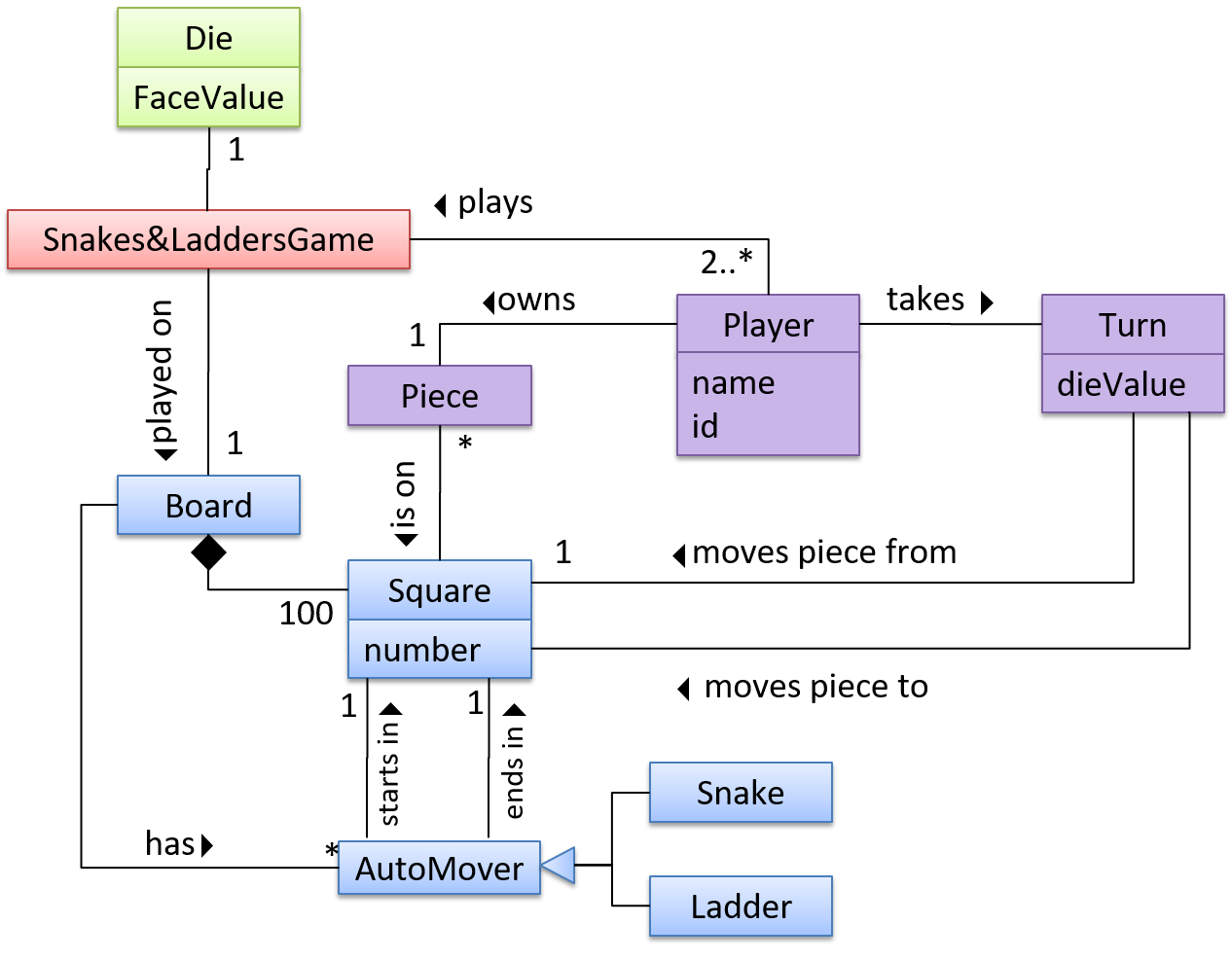

Composition

A composition is an association that represents a strong whole-part relationship.

A Board (used for playing board games) consists of Square objects.

Composition implies,

- when the whole is destroyed, parts are destroyed too i.e., the part cannot exist without being attached to a whole.

- there cannot be cyclical links.

The ‘sub-folder’ association between Folder objects is a composition type association. Consider the case of Folder object subF is a sub-folder of Folder object F. In this case,

- if

Fis deleted,subFwill be deleted with it. Fcannot be a sub-folder ofsubF(i.e., no cyclical 'sub-folder' association between the two objects).

Whether a relationship is a composition can depend on the context.

Is the relationship between Email and EmailSubject composition? That is, is the email subject part of an email to the extent that an email subject cannot exist without an email?

- When modeling an application that sends emails, the answer is 'yes'.

- When modeling an application that gather analytics about email traffic, the answer may be 'no' (e.g., the application might collect just the email subjects for text analysis).

A common use of composition is when parts of a big class are carved out as smaller classes for the ease of managing the internal design. In such cases, the classes extracted out still act as parts of the bigger class and the outside world has no business knowing about them.

Cascading deletion alone is not sufficient for composition. Suppose there is a design in which Person objects are attached to Task objects and the former get deleted whenever the latter is deleted. This fact alone does not mean there is a composition relationship between the two classes. For it to be composition, a Person must be an integral part of a Task in the context of that association, at the concept level (not simply at implementation level).

Identifying and keeping track of composition relationships in the design has benefits such as helping to maintain the data integrity of the system. For example, when you know that a certain relationship is a composition, you can take extra care in your implementation to ensure that when the whole object is deleted, all its parts are deleted too.

Implementing composition

Composition is implemented using a normal variable. If correctly implemented, the ‘part’ object will be deleted when the ‘whole’ object is deleted. Ideally, the ‘part’ object may not even be visible to clients of the ‘whole’ object.

Here is one way to implement the composition between Email and Subject:

class Email {

private Subject subject;

...

}

class Email:

def __init__(self):

self.__subject = Subject()

In this code, the Email has a composition type relationship with the Subject class, in the sense that the subject is part of the email.

Aggregation

Aggregation represents a container-contained relationship. It is a weaker relationship than composition.

SportsClub can act as a container for Person objects who are members of the club. Person objects can survive without a SportsClub object.

Implementing aggregation

Implementation is similar to that of composition except the containee object can exist even after the container object is deleted.

In the code below, there is an aggregation association between the Team class and the Person class in that a Team contains a Person object who is the leader of the team.

class Team {

Person leader;

...

void setLeader(Person p) {

leader = p;

}

}

class Team:

def __init__(self):

self.__leader = None

def set_leader(self, person):

self.__leader = person

Association Classes

An association class represents additional information about an association. It is a normal class but plays a special role from a design point of view.

A Man class and a Woman class are linked with a ‘married to’ association and there is a need to store the date of marriage. However, that data is related to the association rather than specifically owned by either the Man object or the Woman object. In such situations, an additional association class can be introduced, e.g., a Marriage class, to store such information.

Implementing association classes

There is no special way to implement an association class. It can be implemented as a normal class that has variables to represent the endpoint of the association it represents.

In the code below, the Transaction class is an association class that represents a transaction between a Person who is the seller and another Person who is the buyer.

class Transaction {

//all fields are compulsory

Person seller;

Person buyer;

Date date;

String receiptNumber;

Transaction(Person seller, Person buyer, Date date, String receiptNumber) {

//set fields

}

}

What :

The OOP concept Inheritance allows you to define a new class based on an existing class.

For example, you can use inheritance to define an EvaluationReport class based on an existing Report class so that the EvaluationReport class does not have to duplicate data/behaviors that are already implemented in the Report class. The EvaluationReport can inherit the wordCount attribute and the print() method from the base class Report.

- Other names for Base class: Parent class, Superclass

- Other names for Derived class: Child class, Subclass, Extended class

A superclass is said to be more general than the subclass. Conversely, a subclass is said to be more specialized than the superclass.

Applying inheritance on a group of similar classes can result in the common parts among classes being extracted into more general classes.

Man and Woman behave the same way for certain things. However, the two classes cannot be simply replaced with a more general class Person because of the need to distinguish between Man and Woman for certain other things. A solution is to add the Person class as a superclass (to contain the code common to men and women) and let Man and Woman inherit from Person class.

Inheritance implies the derived class can be considered as a subtype of the base class (and the base class is a super-type of the derived class), resulting in an is a relationship.

Inheritance does not necessarily mean a subtype relationship exists. However, the two often go hand-in-hand. For simplicity, at this point let us assume inheritance implies a subtype relationship.

To continue the previous example,

Womanis aPersonManis aPerson

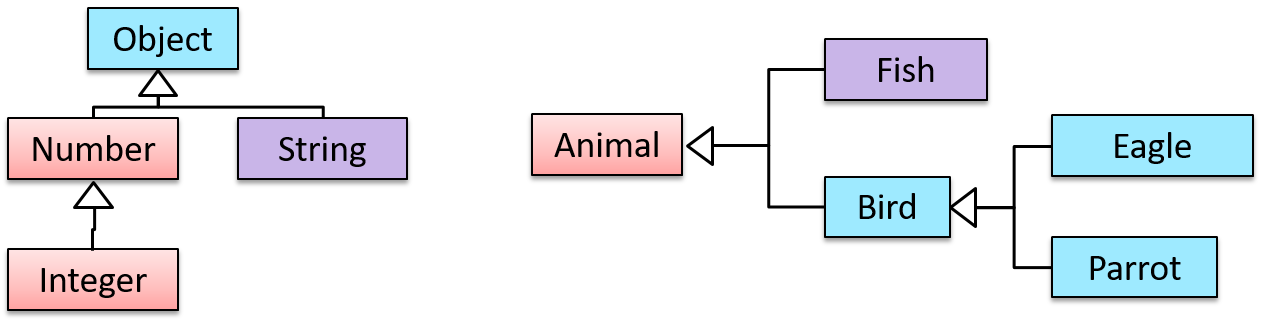

Inheritance relationships through a chain of classes can result in inheritance hierarchies (aka inheritance trees).

Two inheritance hierarchies/trees are given below. Note that the triangle points to the parent class. Observe how the Parrot is a Bird as well as it is an Animal.

Multiple Inheritance is when a class inherits directly from multiple classes. Multiple inheritance among classes is allowed in some languages (e.g., Python, C++) but not in other languages (e.g., Java, C#).

The Honey class inherits from the Food class and the Medicine class because honey can be consumed as a food as well as a medicine (in some oriental medicine practices). Similarly, a Car is a Vehicle, an Asset and a Liability.

Overriding :

Method overriding is when a subclass changes the behavior inherited from the parent class by re-implementing the method. Overridden methods have the same name, the same type signature, and the same (or a subtype of the) return type.

Consider the following case of EvaluationReport class inheriting the Report class:

Report methods | EvaluationReport methods | Overrides? |

|---|---|---|

print() | print() | Yes |

write(String) | write(String) | Yes |

read():String | read(int):String | No. Reason: the two methods have different signatures; This is a case of overloading (rather than overriding). |

Overloading :

Method overloading is when there are multiple methods with the same name but different type signatures. Overloading is used to indicate that multiple operations do similar things but take different parameters.

Type signature: The type signature of an operation is the type sequence of the parameters. The return type and parameter names are not part of the type signature. However, the parameter order is significant.

Example:

| Method | Type Signature |

|---|---|

int add(int X, int Y) | (int, int) |

void add(int A, int B) | (int, int) |

void m(int X, double Y) | (int, double) |

void m(double X, int Y) | (double, int) |

In the case below, the calculate method is overloaded because the two methods have the same name but different type signatures (String) and (int).

calculate(String): voidcalculate(int): void

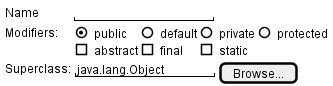

Interfaces :

An interface is a behavior specification i.e., a collection of . If a class , it means the class is able to support the behaviors specified by the said interface.

There are a number of situations in software engineering when it is important for disparate groups of programmers to agree to a "contract" that spells out how their software interacts. Each group should be able to write their code without any knowledge of how the other group's code is written. Generally speaking, interfaces are such contracts. --Oracle Docs on Java

Suppose SalariedStaff is an interface that contains two methods setSalary(int) and getSalary(). AcademicStaff can declare itself as implementing the SalariedStaff interface, which means the AcademicStaff class must implement all the methods specified by the SalariedStaff interface i.e., setSalary(int) and getSalary().

A class implementing an interface results in an is-a relationship, just like in class inheritance.

In the example above, AcademicStaff is a SalariedStaff. An AcademicStaff object can be used anywhere a SalariedStaff object is expected e.g., SalariedStaff ss = new AcademicStaff().

Abstract Classes :

Abstract class: A class declared as an abstract class cannot be instantiated, but it can be subclassed.

You can declare a class as abstract when a class is merely a representation of commonalities among its subclasses in which case it does not make sense to instantiate objects of that class.

The Animal class that exists as a generalization of its subclasses Cat, Dog, Horse, Tiger etc. can be declared as abstract because it does not make sense to instantiate an Animal object.

Abstract method: An abstract method is a method signature without a method implementation.

The move method of the Animal class is likely to be an abstract method as it is not possible to implement a move method at the Animal class level to fit all subclasses because each animal type can move in a different way.

A class that has an abstract method becomes an abstract class because the class definition is incomplete (due to the missing method body) and it is not possible to create objects using an incomplete class definition.

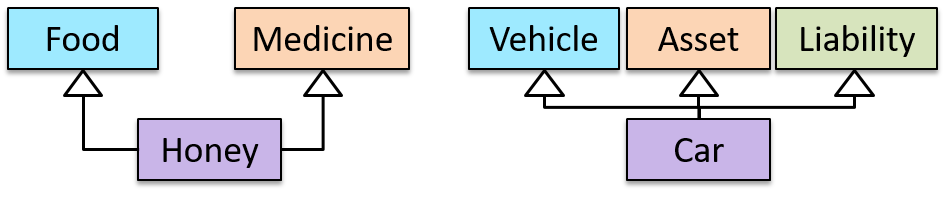

Substitutability :

Every instance of a subclass is an instance of the superclass, but not vice versa. As a result, inheritance allows substitutability: the ability to substitute a child class object where a parent class object is expected.

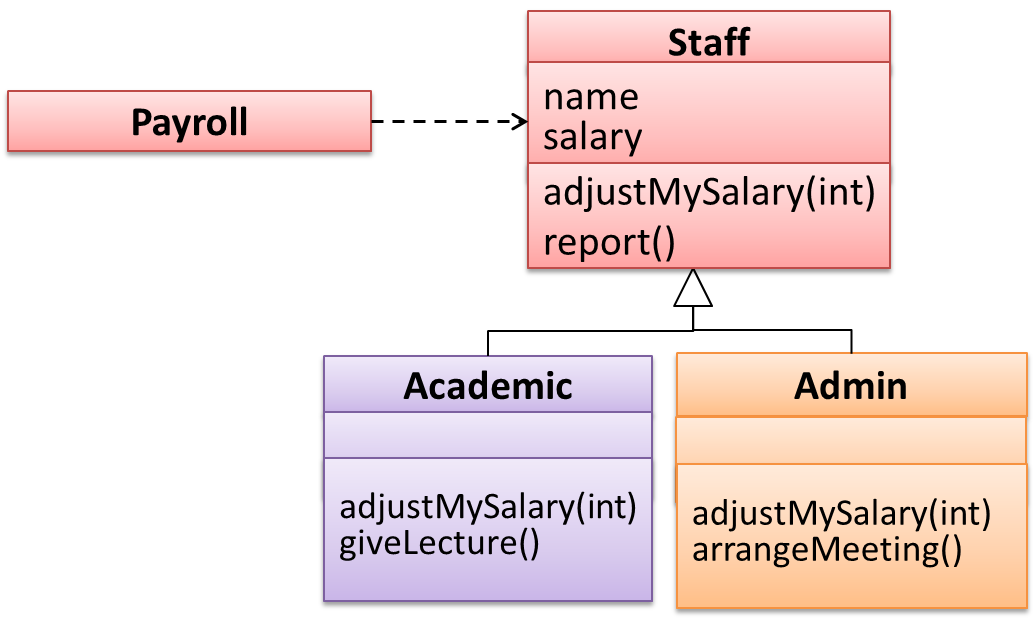

An AcademicStaff is an instance of a Staff, but a Staff is not necessarily an instance of an AcademicStaff. i.e., wherever an object of the superclass is expected, it can be substituted by an object of any of its subclasses.

The following code is valid because an AcademicStaff object is substitutable as a Staff object.

Staff staff = new AcademicStaff(); // OK

But the following code is not valid because staff is declared as a Staff type and therefore its value may or may not be of type AcademicStaff, which is the type expected by variable academicStaff.

Staff staff;

...

AcademicStaff academicStaff = staff; // Not OK

Dynamic and Static Binding :

Dynamic binding (): a mechanism where method calls in code are at , rather than at compile time.

Overridden methods are resolved using dynamic binding, and therefore resolves to the implementation in the actual type of the object.

Consider the code below. The declared type of s is Staff and it appears as if the adjustSalary(int) operation of the Staff class is invoked.

void adjustSalary(int byPercent) {

for (Staff s: staff) {

s.adjustSalary(byPercent);

}

}

However, at runtime s can receive an object of any subclass of Staff. That means the adjustSalary(int) operation of the actual subclass object will be called. If the subclass does not override that operation, the operation defined in the superclass (in this case, Staff class) will be called.

Static binding (aka early binding): When a method call is resolved at compile time.

In contrast, overloaded methods are resolved using static binding.

Note how the constructor is overloaded in the class below. The method call new Account() is bound to the first constructor at compile time.

class Account {

Account() {

// Signature: ()

...

}

Account(String name, String number, double balance) {

// Signature: (String, String, double)

...

}

}

Similarly, the calculateGrade method is overloaded in the code below and a method call calculateGrade("A1213232") is bound to the second implementation, at compile time.

void calculateGrade(int[] averages) { ... }

void calculateGrade(String matric) { ... }

What :

Polymorphism:

The ability of different objects to respond, each in its own way, to identical messages is called polymorphism. -- Object-Oriented Programming with Objective-C, Apple

Polymorphism allows you to write code targeting superclass objects, use that code on subclass objects, and achieve possibly different results based on the actual class of the object.

Assume classes Cat and Dog are both subclasses of the Animal class. You can write code targeting Animal objects and use that code on Cat and Dog objects, achieving possibly different results based on whether it is a Cat object or a Dog object. Some examples:

- Declare an array of type

Animaland still be able to storeDogandCatobjects in it. - Define a method that takes an

Animalobject as a parameter and yet be able to passDogandCatobjects to it. - Call a method on a

Dogor aCatobject as if it is anAnimalobject (i.e., without knowing whether it is aDogobject or aCatobject) and get a different response from it based on its actual class e.g., call theAnimalclass's methodspeak()on objectaand get a"Meow"as the return value ifais aCatobject and"Woof"if it is aDogobject.

Polymorphism literally means "ability to take many forms".

How :

Three concepts combine to achieve polymorphism: substitutability, operation overriding, and dynamic binding.

- Substitutability: Because of substitutability, you can write code that expects objects of a parent class and yet use that code with objects of child classes. That is how polymorphism is able to treat objects of different types as one type.

- Overriding: To get polymorphic behavior from an operation, the operation in the superclass needs to be overridden in each of the subclasses. That is how overriding allows objects of different subclasses to display different behaviors in response to the same method call.

- Dynamic binding: Calls to overridden methods are bound to the implementation of the actual object's class dynamically during the runtime. That is how the polymorphic code can call the method of the parent class and yet execute the implementation of the child class.

Miscellaneous

What is the difference between a Class, an Abstract Class, and an Interface?

- An interface is a behavior specification with no implementation.

- A class is a behavior specification + implementation.

- An abstract class is a behavior specification + a possibly incomplete implementation.

How does overriding differ from overloading?

Overloading is used to indicate that multiple operations do similar things but take different parameters. Overloaded methods have the same method name but different method signatures and possibly different return types.

Overriding is when a sub-class redefines an operation using the same method name and the same type signature. Overridden methods have the same name, same method signature, and same return type.

SECTION: REQUIREMENTS

Introduction

A software requirement specifies a need to be fulfilled by the software product.

A software project may be,

- a brownfield project i.e., develop a product to replace/update an existing software product

- a greenfield project i.e., develop a totally new system from scratch

In either case, requirements need to be gathered, analyzed, specified, and managed.

Requirements come from stakeholders.

Stakeholder: An individual or an organization that is involved or potentially affected by the software project. e.g., users, sponsors, developers, interest groups, government agencies, etc.

Identifying requirements is often not easy. For example, stakeholders may not be aware of their precise needs, may not know how to communicate their requirements correctly, may not be willing to spend effort in identifying requirements, etc.

Non-Functional Requirements

Requirements can be divided into two in the following way:

- Functional requirements specify what the system should do.

- Non-functional requirements specify the constraints under which the system is developed and operated.

Some examples of non-functional requirement categories:

- Data requirements e.g. size, , etc.,

- Environment requirements e.g. technical environment in which the system would operate in or needs to be compatible with.

- Accessibility, Capacity, Compliance with regulations, Documentation, Disaster recovery, Efficiency, Extensibility, Fault tolerance, Interoperability, Maintainability, Privacy, Portability, Quality, Reliability, Response time, Robustness, Scalability, Security, Stability, Testability, and more ...

You may have to spend an extra effort in digging NFRs out as early as possible because,

- NFRs are easier to miss e.g., stakeholders tend to think of functional requirements first

- sometimes NFRs are critical to the success of the software. E.g. A web application that is too slow or that has low security is unlikely to succeed even if it has all the right functionality.

Quality of Requirements

Here are some characteristics of well-defined requirements [📖 zielczynski]:

- Unambiguous

- Testable (verifiable)

- Clear (concise, terse, simple, precise)

- Correct

- Understandable

- Feasible (realistic, possible)

- Independent

- Necessary

- Implementation-free (i.e., abstract)

Besides these criteria for individual requirements, the set of requirements as a whole should be

- Consistent

- Non-redundant

- Complete

Prioritizing Requirements

Requirements can be prioritized based on the importance and urgency, while keeping in mind the constraints of schedule, budget, staff resources, quality goals, and other constraints.

A common approach is to group requirements into priority categories. Note that all such scales are subjective, and stakeholders define the meaning of each level in the scale for the project at hand.

An example scheme for categorizing requirements:

Essential: The product must have this requirement fulfilled or else it does not get user acceptance.Typical: Most similar systems have this feature although the product can survive without it.Novel: New features that could differentiate this product from the rest.

Other schemes:

High,Medium,LowMust-have,Nice-to-have,Unlikely-to-haveLevel 0,Level 1,Level 2, ...

Some requirements can be discarded if they are considered ‘out of ’.

The requirement given below is for a Calendar application. Stakeholders of the software (e.g. product designers) might decide the following requirement is not in the scope of the software.

The software records the actual time taken by each task and show the difference between the actual and scheduled time for the task.

Brainstorming

Brainstorming: A group activity designed to generate a large number of diverse and creative ideas for the solution of a problem.

In a brainstorming session there are no "bad" ideas. The aim is to generate ideas; not to validate them. Brainstorming encourages you to "think outside the box" and put "crazy" ideas on the table without fear of rejection.

User Surveys

Surveys can be used to solicit responses and opinions from a large number of stakeholders regarding a current product or a new product.

Observation

Observing users in their natural work environment can uncover product requirements. Usage data of an existing system can also be used to gather information about how an existing system is being used, which can help in building a better replacement e.g. to find the situations where the user makes mistakes when using the current system.

Interviews

Interviewing stakeholders and domain experts can produce useful information about project requirements.

Focus Groups

[source]

Focus groups are a kind of informal interview within an interactive group setting. A group of people (e.g. potential users, beta testers) are asked about their understanding of a specific issue, process, product, advertisement, etc.

Prototyping

Prototype: A prototype is a mock up, a scaled down version, or a partial system constructed

- to get users’ feedback.

- to validate a technical concept (a "proof-of-concept" prototype).

- to give a preview of what is to come, or to compare multiple alternatives on a small scale before committing fully to one alternative.

- for early field-testing under controlled conditions.

Prototyping can uncover requirements, in particular, those related to how users interact with the system. UI prototypes or mock ups are often used in brainstorming sessions, or in meetings with the users to get quick feedback from them.

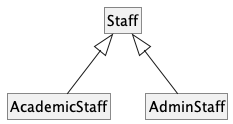

A mock up (also called a wireframe diagram) of a dialog box:

[source: plantuml.com]

Prototyping can be used for discovering as well as specifying requirements e.g. a UI prototype can serve as a specification of what to build.

Product Surveys

Studying existing products can unearth shortcomings of existing solutions that can be addressed by a new product. Product manuals and other forms of documentation of an existing system can tell us how the existing solutions work.

When developing a game for a mobile device, a look at a similar PC game can give insight into the kind of features and interactions the mobile game can offer.

What

A textual description (i.e., prose) can be used to describe requirements. Prose is especially useful when describing abstract ideas such as the vision of a product.

The product vision of the TEAMMATES Project given below is described using prose.

TEAMMATES aims to become the biggest student project in the world (biggest here refers to 'many contributors, many users, large codebase, evolving over a long period'). Furthermore, it aims to serve as a training tool for Software Engineering students who want to learn SE skills in the context of a non-trivial real software product.

Avoid using lengthy prose to describe requirements; they can be hard to follow.

What

Feature list: A list of features of a product grouped according to some criteria such as aspect, priority, order of delivery, etc.

A sample feature list from a simple Minesweeper game (only a brief description has been provided to save space):

- Basic play – Single player play.

- Difficulty levels

- Medium levels

- Advanced levels

- Versus play – Two players can play against each other.

- Timer – Additional fixed time restriction on the player.

- ...

Introduction

User story: User stories are short, simple descriptions of a feature told from the perspective of the person who desires the new capability, usually a user or customer of the system. [Mike Cohn]

A common format for writing user stories is:

User story format: As a {user type/role} I can {function} so that {benefit}

Examples (from a Learning Management System):

- As a student, I can download files uploaded by lecturers, so that I can get my own copy of the files

- As a lecturer, I can create discussion forums, so that students can discuss things online

- As a tutor, I can print attendance sheets, so that I can take attendance during the class

You can write user stories using a physical medium or a digital tool. For example, you can use index cards or sticky notes, and arrange them on walls or tables. Alternatively, you can use a software (e.g., GitHub Project Boards, Trello, Google Docs, ...) to manage user stories digitally.

Details

The {benefit} can be omitted if it is obvious.

As a user, I can login to the system so that I can access my data

It is recommended to confirm there is a concrete benefit even if you omit it from the user story. If not, you could end up adding features that have no real benefit.

You can add more characteristics to the {user role} to provide more context to the user story.

- As a forgetful user, I can view a password hint, so that I can recall my password.

- As an expert user, I can tweak the underlying formatting tags of the document, so that I can format the document exactly as I need.

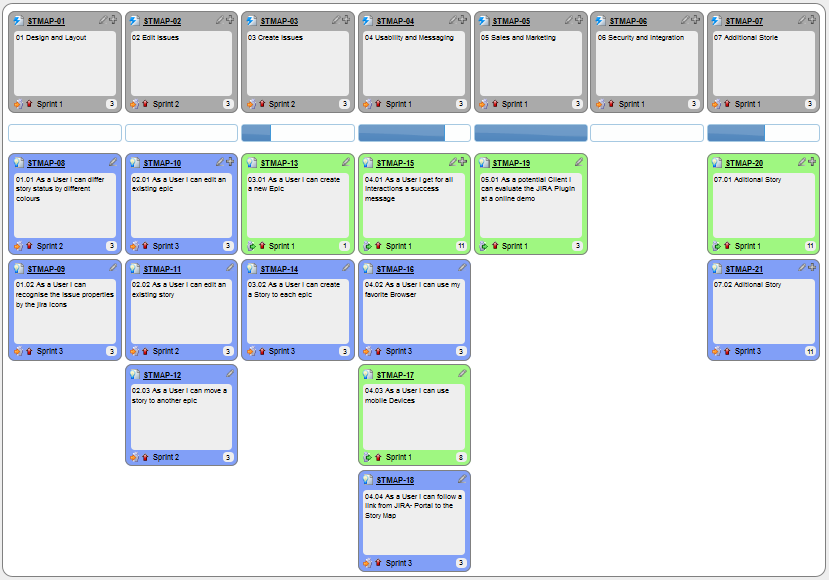

You can write user stories at various levels. High-level user stories, called epics (or themes) cover bigger functionality. You can then break down these epics to multiple user stories of normal size.

[Epic] As a lecturer, I can monitor student participation levels

- As a lecturer, I can view the forum post count of each student

so that I can identify the activity level of students in the forum - As a lecturer, I can view webcast view records of each student

so that I can identify the students who did not view webcasts - As a lecturer, I can view file download statistics of each student

so that I can identify the students who did not download lecture materials

You can add conditions of satisfaction to a user story to specify things that need to be true for the user story implementation to be accepted as ‘done’.

As a lecturer, I can view the forum post count of each student so that I can identify the activity level of students in the forum.

Conditions:

Separate post count for each forum should be shown

Total post count of a student should be shown

The list should be sortable by student name and post count

Other useful info that can be added to a user story includes (but not limited to)

- Priority: how important the user story is

- Size: the estimated effort to implement the user story

- Urgency: how soon the feature is needed

Usage

User stories capture user requirements in a way that is convenient for , , and .

[User stories] strongly shift the focus from writing about features to discussing them. In fact, these discussions are more important than whatever text is written. [Mike Cohn, MountainGoat Software 🔗]

User stories differ from mainly in the level of detail. User stories should only provide enough details to make a reasonably low risk estimate of how long the user story will take to implement. When the time comes to implement the user story, the developers will meet with the customer face-to-face to work out a more detailed description of the requirements. [more...]

User stories can capture non-functional requirements too because even NFRs must benefit some stakeholder.

An example of an NFR captured as a user story:

| As a/an ___, | I want to ___, | so that ___. |

|---|---|---|

| impatient user | to be able to experience reasonable response time from the website while up to 1000 concurrent users are using it | I can use the app even when the traffic is at the maximum expected level |

Given their lightweight nature, user stories are quite handy for recording requirements during early stages of requirements gathering.

A recipe for brainstorming user stories

Given below is a possible recipe you can take when using user stories for early stages of requirement gathering.

Step 0: Clear your mind of preconceived product ideas

Even if you already have some idea of what your product will look/behave like in the end, clear your mind of those ideas. The product is the solution. At this point, we are still at the stage of figuring out the problem (i.e., user requirements). Let's try to get from the problem to the solution in a systematic way, one step at a time.

Step 1: Define the target user as a persona:

Decide your target user's profile (e.g. a student, office worker, programmer, salesperson) and work patterns (e.g. Does he work in groups or alone? Does he share his computer with others?). A clear understanding of the target user will help when deciding the importance of a user story. You can even narrow it down to a persona. Here is an example:

Jean is a university student studying in a non-IT field. She interacts with a lot of people due to her involvement in university clubs/societies. ...

Step 2: Define the problem scope:

Decide the exact problem you are going to solve for the target user. It is also useful to specify what related problems it will not solve so that the exact scope is clear.

ProductX helps Jean keep track of all her school contacts. It does not cover communicating with contacts.

Step 3: List scenarios to form a narrative:

Think of the various scenarios your target user is likely to go through as she uses your app. Following a chronological sequence as if you are telling a story might be helpful.

A. First use:

- Jean gets to know about ProductX. She downloads it and launches it to check out what it can do.

- After playing around with the product for a bit, Jean wants to start using it for real.

- ...

B. Second use: (Jean is still a beginner)

- Jean launches ProductX. She wants to find ...

- ...

C. 10th use: (Jean is a little bit familiar with the app)

- ...

D. 100th use: (Jean is an expert user)

- Jean launches the app and does ... and ... followed by ... as per her usual habit.

- Jean feels some of the data in the app are no longer needed. She wants to get rid of them to reduce clutter.

More examples that might apply to some products:

- Jean uses the app at the start of the day to ...

- Jean uses the app before going to sleep to ...

- Jean hasn't used the app for a while because she was on a three-month training programme. She is now back at work and wants to resume her daily use of the app.

- Jean moves to another company. Some of her clients come with her but some don't.

- Jean starts freelancing in her spare time. She wants to keep her freelancing clients separate from her other clients.

Step 4: List the user stories to support the scenarios:

Based on the scenarios, decide on the user stories you need to support. For example, based on the scenario 'A. First use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As a potential user exploring the app, I can see the app populated with sample data, so that I can easily see how the app will look like when it is in use.

- As a user ready to start using the app, I can purge all current data, so that I can get rid of sample/experimental data I used for exploring the app.

To give another example, based on the scenario 'D. 100th use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As an expert user, I can create shortcuts for tasks, so that I can save time on frequently performed tasks.

- As a long-time user, I can archive/hide unused data, so that I am not distracted by irrelevant data.

Do not 'evaluate' the value of user stories while brainstorming. Reason: an important aspect of brainstorming is not judging the ideas generated.

Other tips:

- Don't be too hasty to discard 'unusual' user stories: Those might make your product unique and stand out from the rest, at least for the target users.

- Don't go into too much detail:

For example, consider this user story:

As a user, I want to see a list of tasks that need my attention most at the present time, so that I pay attention to them first.

When discussing this user story, don't worry about what tasks should be considered 'needs my attention most at the present time'. Those details can be worked out later. - Don't be biased by preconceived product ideas: When you are at the stage of identifying user needs, clear your mind of ideas you have about what your end product will look like. That is, don't try to reverse-engineer a preconceived product idea into user stories.

- Don't discuss implementation details or whether you are actually going to implement it: When gathering requirements, your decision is whether the user's need is important enough for you to want to fulfil it. Implementation details can be discussed later. If a user story turns out to be too difficult to implement later, you can always omit it from the implementation plan.

While user stories can be recorded on in the initial stages, an online tool is more suitable for longer-term management of user stories, especially if the team is not .

Introduction

Use case: A description of a set of sequences of actions, including variants, that a system performs to yield an observable result of value to an actor [ 📖 : ].

A use case describes an interaction between the user and the system for a specific functionality of the system.

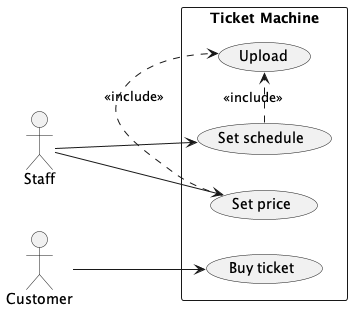

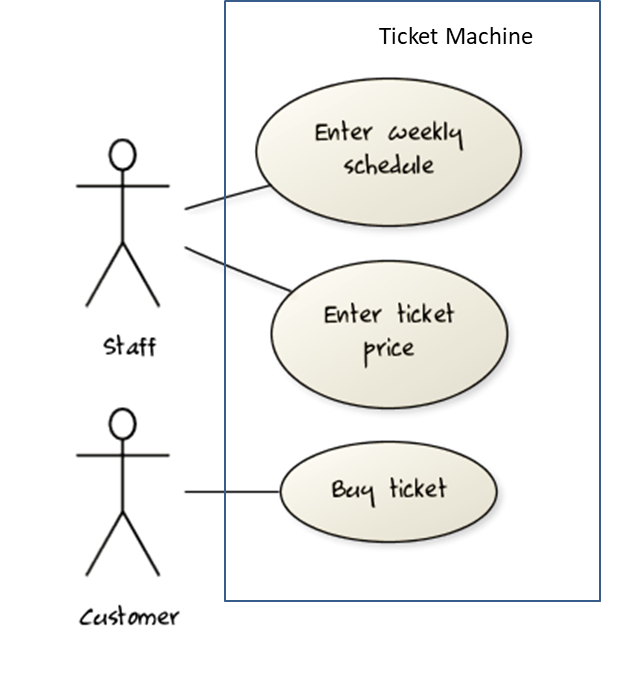

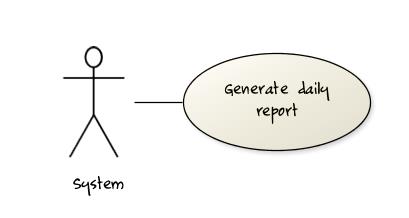

UML includes a diagram type called use case diagrams that can illustrate use cases of a system visually, providing a visual ‘table of contents’ of the use cases of a system.

In the example on the right, note how use cases are shown as ovals and user roles relevant to each use case are shown as stick figures connected to the corresponding ovals.

Use cases capture the functional requirements of a system.

Identifying

A use case is an interaction between a system and its actors.

Actors in Use Cases

Actor: An actor (in a use case) is a role played by a user. An actor can be a human or another system. Actors are not part of the system; they reside outside the system.

Some example actors for a Learning Management System:

- Actors: Guest, Student, Staff, Admin, , .

A use case can involve multiple actors.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Use case: UC01 Conduct Survey

- Actors: Staff, Student

An actor can be involved in many use cases.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Actor: Staff

- Use cases: UC01 Conduct Survey, UC02 Set Up Course Schedule, UC03 Email Class, ...

A single person/system can play many roles.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Person: a student

- Actors (or Roles): Student, Guest, Tutor

Many persons/systems can play a single role.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Actor (or role): Student

- Persons that can play this role: undergraduate student, graduate student, a staff member doing a part-time course, exchange student

Use cases can be specified at various levels of detail.

Consider the three use cases given below. Clearly, (a) is at a higher level than (b) and (b) is at a higher level than (c).

- System: LearnSys

- Use cases:

a. Conduct a survey

b. Take the survey

c. Answer survey question

While modeling user-system interactions,

- start with high level use cases and progressively work toward lower level use cases.

- be mindful of which level of detail you are working at and not to mix use cases of different levels.

Details

Writing use case steps

The main body of the use case is a sequence of steps that describes the interaction between the system and the actors. Each step is given as a simple statement describing who does what.

An example of the main body of a use case.

- Student requests to upload file

- LMS requests for the file location

- Student specifies the file location

- LMS uploads the file

A use case describes only the externally visible behavior, not internal details, of a system i.e., should minimize details that are not part of the interaction between the user and the system.

This example use case step refers to a behavior not externally visible (i.e., user is not meant to be aware of).

- LMS saves the file into the cache and indicates success.

A step gives the intention of the actor (not the mechanics). That means UI details are usually omitted. The idea is to leave as much flexibility to the UI designer as possible. That is, the use case specification should be as general as possible (less specific) about the UI.

The first example below is not a good use case step because it contains UI-specific details. The second one is better because it omits UI-specific details.

Bad : User right-clicks the text box and chooses ‘clear’

Good : User clears the input

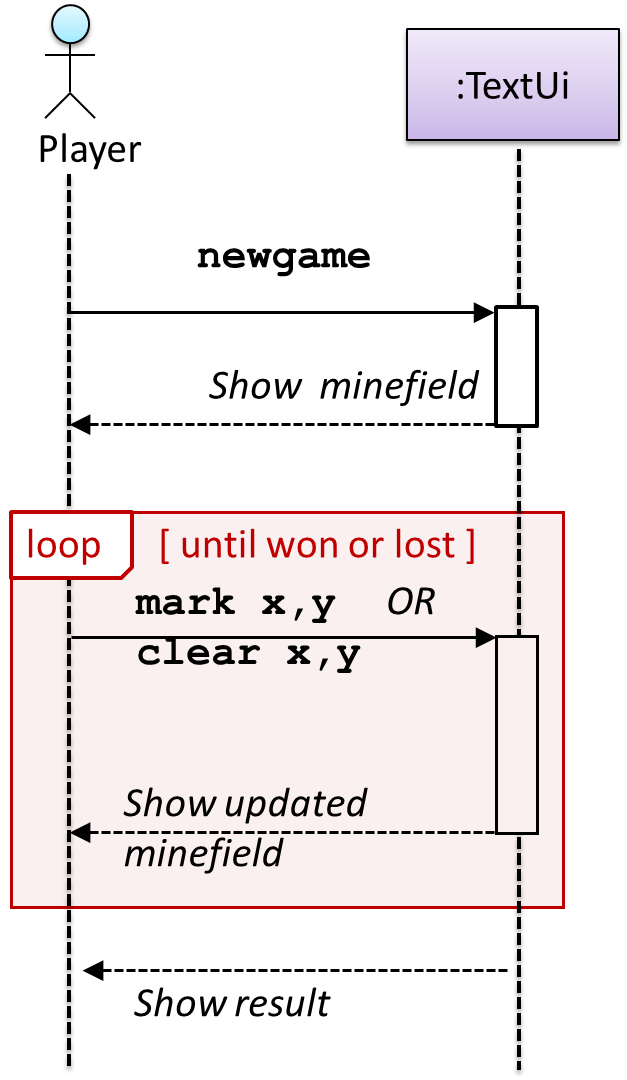

A use case description can show loops too.

An example of how you can show a loop:

Software System: SquareGame

Use case: - Play a Game

Actors: Player (multiple players)

MSS:

- A Player starts the game.

- SquareGame asks for player names.

- Each Player enters his own name.

- SquareGame shows the order of play.

- SquareGame prompts for the current Player to throw a die.

- Current Player adjusts the throw speed.

- Current Player triggers the die throw.

- SquareGame shows the face value of the die.

- SquareGame moves the Player's piece accordingly.

Steps 5-9 are repeated for each Player, and for as many rounds as required until a Player reaches the 100th square. - SquareGame shows the Winner.

Use case ends.

The Main Success Scenario (MSS) describes the most straightforward interaction for a given use case, which assumes that nothing goes wrong. This is also called the Basic Course of Action or the Main Flow of Events of a use case.

Note how the MSS in the example below assumes that all entered details are correct and ignores problems such as timeouts, network outages etc. For example, the MSS does not tell us what happens if the user enters incorrect data.

System: Online Banking System (OBS)

Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money

Actor: User

MSS:

- User chooses to transfer money.

- OBS requests for details of the transfer.

- User enters the requested details.

- OBS requests for confirmation.

- OBS transfers the money and displays the new account balance.

Use case ends.

Extensions are "add-on"s to the MSS that describe exceptional/alternative flow of events. They describe variations of the scenario that can happen if certain things are not as expected by the MSS. Extensions appear below the MSS.

This example adds some extensions to the use case in the previous example.

System: Online Banking System (OBS) Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money Actor: User MSS: 1. User chooses to transfer money. 2. OBS requests for details of the transfer. 3. User enters the requested details. 4. OBS requests for confirmation. 5. User confirms. 6. OBS transfers the money and displays the new account balance. Use case ends.

Extensions:

3a. OBS detects an error in the entered data.

3a1. OBS requests for the correct data.

3a2. User enters new data.

Steps 3a1-3a2 are repeated until the data entered are correct.

Use case resumes from step 4.

3b. User requests to effect the transfer in a future date.

3b1. OBS requests for confirmation.

3b2. User confirms future transfer.

Use case ends.

*a. At any time, User chooses to cancel the transfer.

*a1. OBS requests to confirm the cancellation.

*a2. User confirms the cancellation.

Use case ends.

*b. At any time, 120 seconds lapse without any input from the User.

*b1. OBS cancels the transfer.

*b2. OBS informs the User of the cancellation.

Use case ends.

Note that the numbering style is not a universal rule but a widely used convention. Based on that convention,

- either of the extensions marked

3a.and3b.can happen just after step3of the MSS. - the extension marked as

*a.can happen at any step (hence, the*).

When separating extensions from the MSS, keep in mind that the MSS should be self-contained. That is, the MSS should give us a complete usage scenario.

Also note that it is not useful to mention events such as power failures or system crashes as extensions because the system cannot function beyond such catastrophic failures.

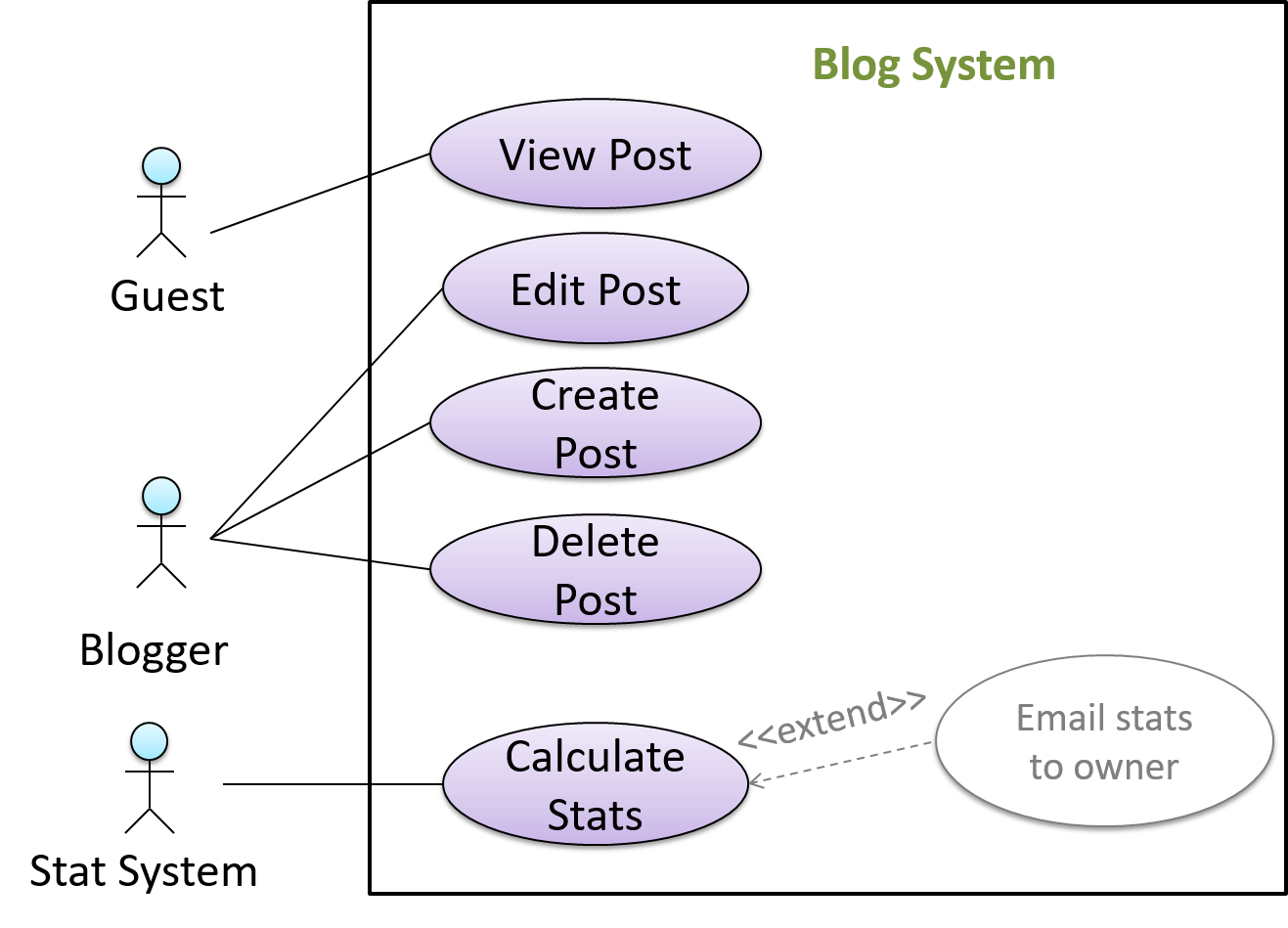

In use case diagrams you can use the <<extend>> arrows to show extensions. Note the direction of the arrow is from the extension to the use case it extends and the arrow uses a dashed line.

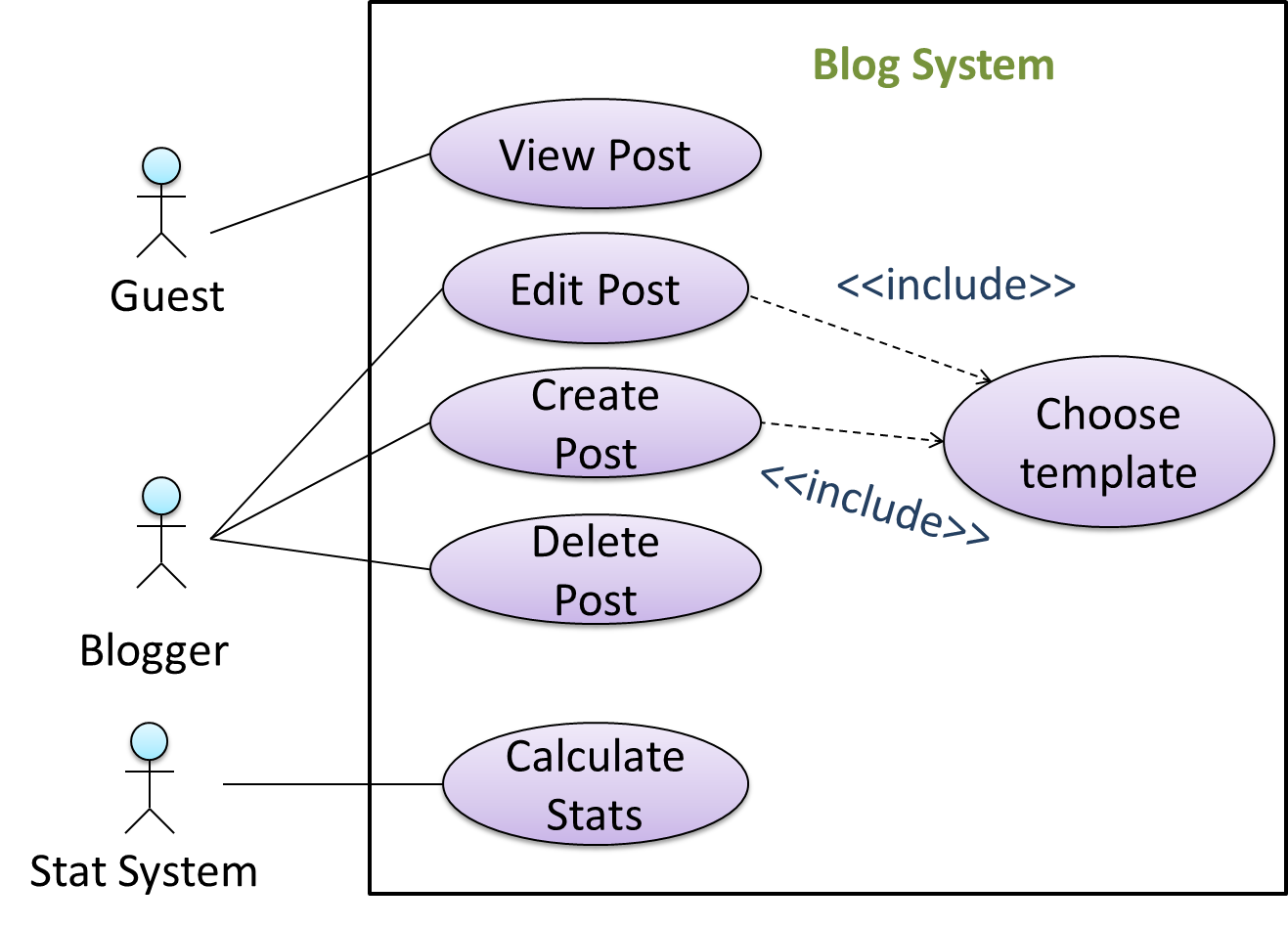

A use case can include another use case. Underlined text is used to show an inclusion of a use case.

This use case includes two other use cases, one in step 1 and one in step 2.

- Software System: LearnSys

- Use case: UC01 - Conduct Survey

- Actors: Staff, Student

- MSS:

- Staff creates the survey (UC44).

- Student completes the survey (UC50).

- Staff views the survey results.

Use case ends.

Inclusions are useful,

- when you don't want to clutter a use case with too many low-level steps.

- when a set of steps is repeated in multiple use cases.

You use a dotted arrow and an <<include>> annotation to show use case inclusions in a use case diagram. Note how the arrow direction is different from the <<extend>> arrows.

Preconditions specify the specific state you expect the system to be in before the use case starts.

Software System: Online Banking System

Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money

Actor: User

Preconditions: User is logged in

MSS:

- User chooses to transfer money.

- OBS requests for details for the transfer.

...

Guarantees specify what the use case promises to give us at the end of its operation.

Software System: Online Banking System

Use case: UC23 - Transfer Money

Actor: User

Preconditions: User is logged in.

Guarantees:

- Money will be deducted from the source account only if the transfer to the destination account is successful.

- The transfer will not result in the account balance going below the minimum balance required.

MSS:

- User chooses to transfer money.

- OBS requests for details for the transfer.

...

Usage

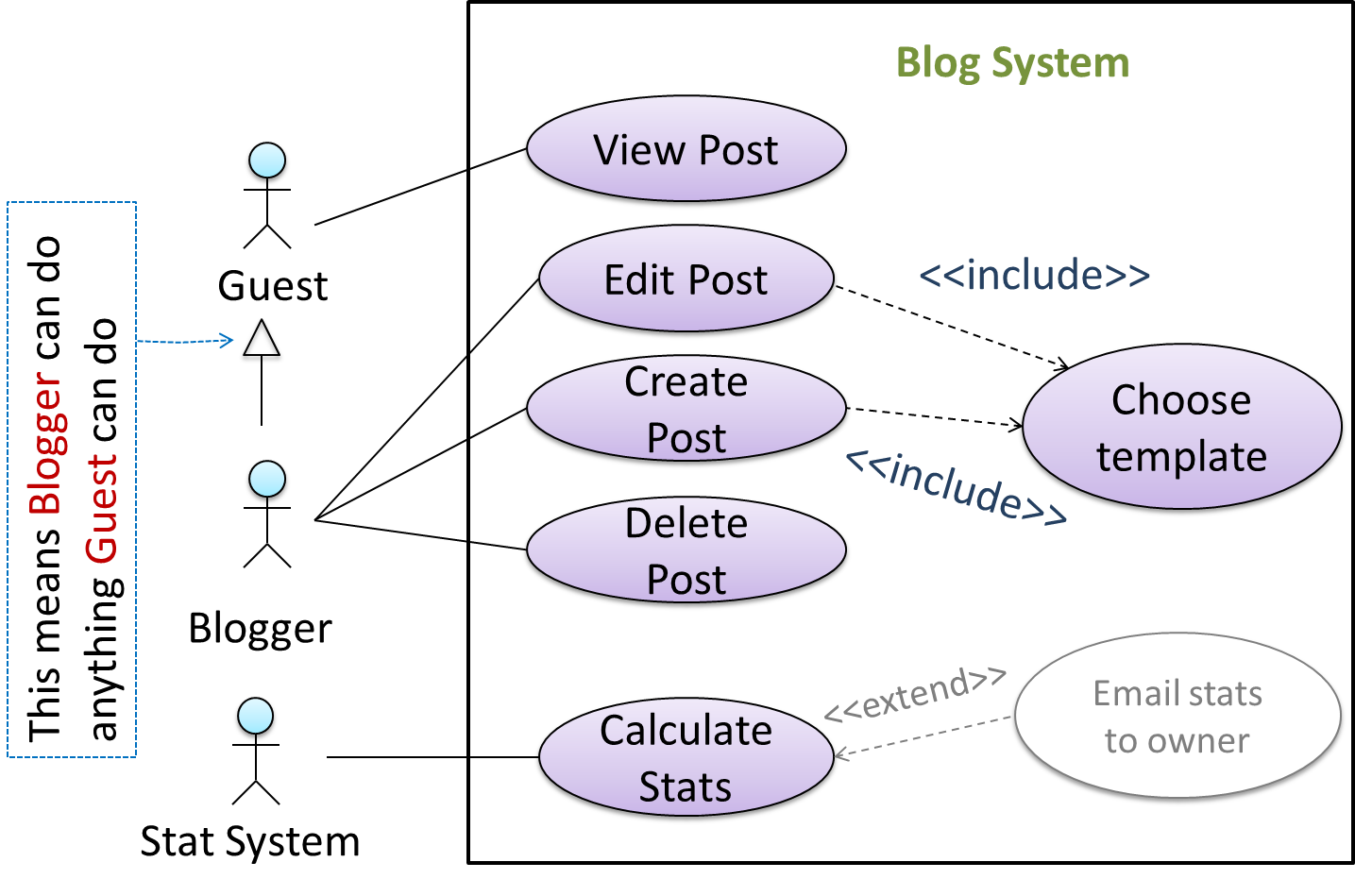

You can use actor generalization in use case diagrams using a symbol similar to that of UML notation for inheritance.

In this example, actor Blogger can do all the use cases the actor Guest can do, as a result of the actor generalization relationship given in the diagram.

Do not over-complicate use case diagrams by trying to include everything possible. A use case diagram is a brief summary of the use cases that is used as a starting point. Details of the use cases can be given in the use case descriptions.

Some include ‘System’ as an actor to indicate that something is done by the system itself without being initiated by a user or an external system.

The diagram below can be used to indicate that the system generates daily reports at midnight.

However, others argue that only use cases providing value to an external user/system should be shown in the use case diagram. For example, they argue that view daily report should be the use case and generate daily report is not to be shown in the use case diagram because it is simply something the system has to do to support the view daily report use case.

You are recommended to follow the latter view (i.e., not to use System as a user). Limit use cases for modeling behaviors that involve an external actor.

UML is not very specific about the text contents of a use case. Hence, there are many styles for writing use cases. For example, the steps can be written as a continuous paragraph.

Use cases should be easy to read. Note that there is no strict rule about writing all details of all steps or a need to use all the elements of a use case.

There are some advantages of documenting system requirements as use cases:

- Because they use a simple notation and plain English descriptions, they are easy for users to understand and give feedback.

- They decouple user intention from mechanism (note that use cases should not include UI-specific details), allowing the system designers more freedom to optimize how a functionality is provided to a user.

- Identifying all possible extensions encourages us to consider all situations that a software product might face during its operation.

- Separating typical scenarios from special cases encourages us to optimize the typical scenarios.

One of the main disadvantages of use cases is that they are not good for capturing requirements that do not involve a user interacting with the system. Hence, they should not be used as the sole means to specify requirements.

What

Glossary: A glossary serves to ensure that all stakeholders have a common understanding of the noteworthy terms, abbreviations, acronyms etc.

Here is a partial glossary from a variant of the Snakes and Ladders game:

- Conditional square: A square that specifies a specific face value which a player has to throw before his/her piece can leave the square.

- Normal square: a normal square does not have any conditions, snakes, or ladders in it.

Specifying a term in the glossary is useful in the following cases:

- A domain-specific/technical term that may not be known to all stakeholders, to indicate its definition

- When a term has multiple meanings, to indicate which of them is used in the project

- When there are multiple terms used for the same concept, to indicate which of them will be used in the project

SECTION: DESIGN

What

Design is the creative process of transforming the problem into a solution; the solution is also called design. -- 📖 Software Engineering Theory and Practice, Shari Lawrence; Atlee, Joanne M. Pfleeger

Software design has two main aspects:

- Product/external design: designing the external behavior of the product to meet the users' requirements. This is usually done by product designers with input from business analysts, user experience experts, user representatives, etc.

- Implementation/internal design: designing how the product will be implemented to meet the required external behavior. This is usually done by software architects and software engineers.

What

Abstraction is a technique for dealing with complexity. It works by establishing a level of complexity we are interested in, and suppressing the more complex details below that level.

The guiding principle of abstraction is that only details that are relevant to the current perspective or the task at hand need to be considered. As most programs are written to solve complex problems involving large amounts of intricate details, it is impossible to deal with all these details at the same time. That is where abstraction can help.

Data abstraction: abstracting away the lower level data items and thinking in terms of bigger entities

Within a certain software component, you might deal with a user data type, while ignoring the details contained in the user data item such as name, and date of birth. These details have been ‘abstracted away’ as they do not affect the task of that software component.

Control abstraction: abstracting away details of the actual control flow to focus on tasks at a higher level

print(“Hello”) is an abstraction of the actual output mechanism within the computer.

Abstraction can be applied repeatedly to obtain progressively higher levels of abstraction.

An example of different levels of data abstraction: a File is a data item that is at a higher level than an array and an array is at a higher level than a bit.

An example of different levels of control abstraction: execute(Game) is at a higher level than print(Char) which is at a higher level than an Assembly language instruction MOV.

Abstraction is a general concept that is not limited to just data or control abstractions.

Some more general examples of abstraction:

- An OOP class is an abstraction over related data and behaviors.

- An architecture is a higher-level abstraction of the design of a software.

- Models (e.g., UML models) are abstractions of some aspect of reality.

What

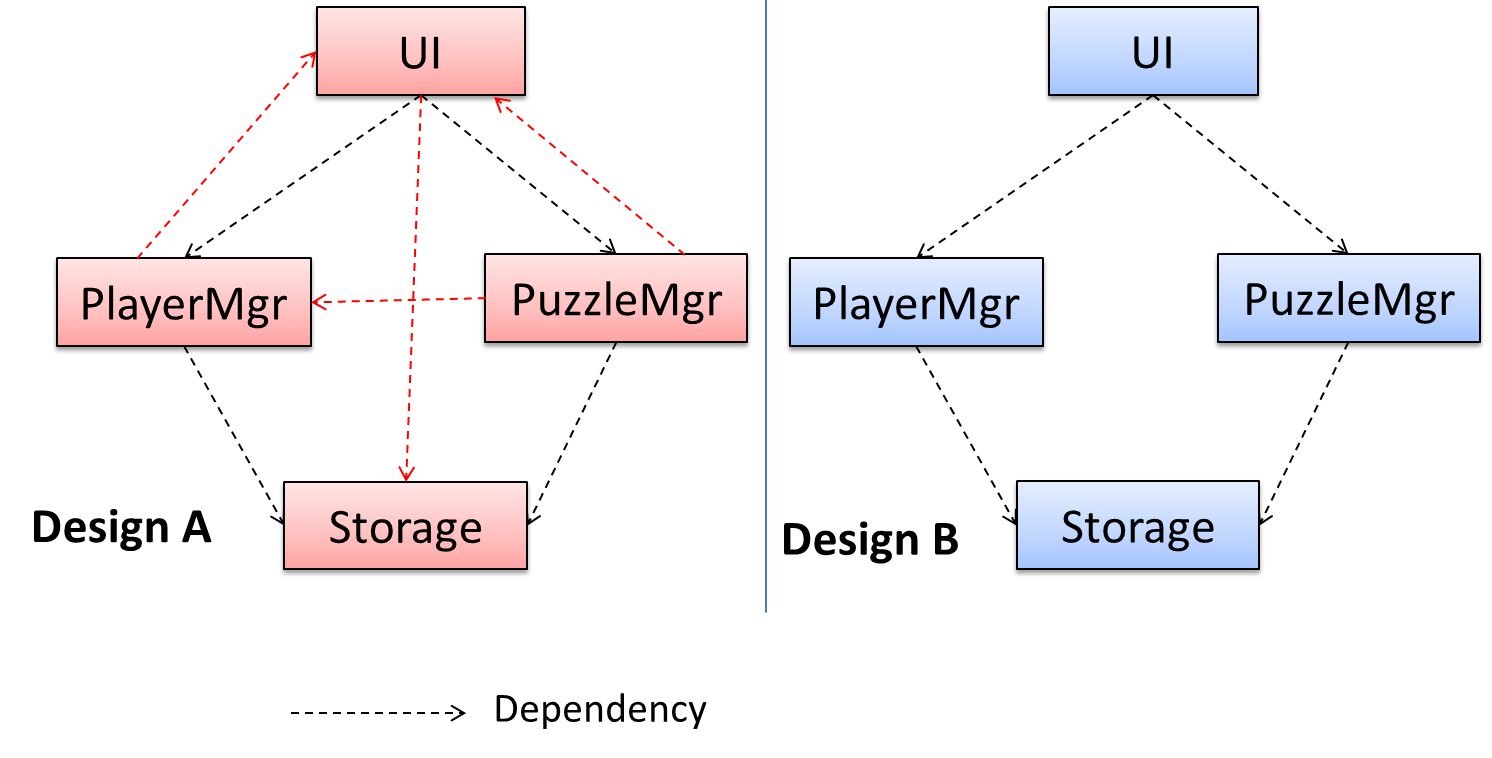

Coupling is a measure of the degree of dependence between components, classes, methods, etc. Low coupling indicates that a component is less dependent on other components. High coupling (aka tight coupling or strong coupling) is discouraged due to the following disadvantages:

- Maintenance is harder because a change in one module could cause changes in other modules coupled to it (i.e., a ripple effect).

- Integration is harder because multiple components coupled with each other have to be integrated at the same time.

- Testing and reuse of the module is harder due to its dependence on other modules.

In the example below, design A appears to have more coupling between the components than design B.

How

X is coupled to Y if a change to Y can potentially require a change in X.

If the Foo class calls the method Bar#read(), Foo is coupled to Bar because a change to Bar can potentially (but not always) require a change in the Foo class e.g. if the signature of Bar#read() is changed, Foo needs to change as well, but a change to the Bar#write() method may not require a change in the Foo class because Foo does not call Bar#write().

Some examples of coupling: A is coupled to B if,

Ahas access to the internal structure ofB(this results in a very high level of coupling)AandBdepend on the same global variableAcallsBAreceives an object ofBas a parameter or a return valueAinherits fromBAandBare required to follow the same data format or communication protocol

What

Cohesion is a measure of how strongly-related and focused the various responsibilities of a component are. A highly-cohesive component keeps related functionalities together while keeping out all other unrelated things.

Higher cohesion is better. Disadvantages of low cohesion (aka weak cohesion):

- Lowers the understandability of modules as it is difficult to express module functionalities at a higher level.

- Lowers maintainability because a module can be modified due to unrelated causes (reason: the module contains code unrelated to each other) or many modules may need to be modified to achieve a small change in behavior (reason: because the code related to that change is not localized to a single module).

- Lowers reusability of modules because they do not represent logical units of functionality.

How

Cohesion can be present in many forms. Some examples:

- Code related to a single concept is kept together, e.g. the

Studentcomponent handles everything related to students. - Code that is invoked close together in time is kept together, e.g. all code related to initializing the system is kept together.

- Code that manipulates the same data structure is kept together, e.g. the

GameArchivecomponent handles everything related to the storage and retrieval of game sessions.

Suppose a Payroll application contains a class that deals with writing data to the database. If the class includes some code to show an error dialog to the user if the database is unreachable, that class is not cohesive because it seems to be interacting with the user as well as the database.

What

A model is a representation of something else.

A class diagram is a model that represents a software design.

A model provides a simpler view of a complex entity because a model captures only a selected aspect. This omission of some aspects implies models are abstractions.

A class diagram captures the structure of the software design but not the behavior.

Multiple models of the same entity may be needed to capture it fully.

In addition to a class diagram (or even multiple class diagrams), a number of other diagrams may be needed to capture various interesting aspects of the software.

How

In software development, models are useful in several ways:

a) To analyze a complex entity related to software development.

Some examples of using models for analysis:

- Models of the can be built to aid the understanding of the problem to be solved.

- When planning a software solution, models can be created to figure out how the solution is to be built. An architecture diagram is such a model.