Target Usage: To back up a Git repository on a cloud-based Git service such as GitHub.

Motivation: One (of several) benefits of maintaining a copy of a repo on a cloud server: it acts as a safety net (e.g., against the folder becoming inaccessible due to a hardware fault).

Lesson plan:

T2L1. Remote Repositories covers that part.

T2L2. Preparing to use GitHub covers that part.

T2L3. Creating a Repo on GitHub covers that part.

T2L4. Linking a Local Repo With a Remote Repo covers that part.

T2L5. Updating the Remote Repo covers that part.

T2L6. Omitting Files from Revision Control covers that part.

To back up your Git repo on the cloud, you’ll need to use a remote repository service, such as GitHub.

A repo you have on your computer is called a local repo. A remote repo is a repo hosted on a remote computer and allows remote access. Some use cases for remote repositories:

- a)as a backup of your local repo

- b)as an intermediary repo to work on the same files from multiple computers

- c)for sharing the revision history of a codebase among team members of a multi-person project

It is possible to set up a Git remote repo on your own server, but an easier option is to use a remote repo hosting service such as GitHub.

To use GitHub, you need to sign up for an account, and configure related tools/settings first.

GitHub is a web-based service that hosts Git repositories and adds collaboration features on top of Git. Two other similar platforms are GitLab and Bitbucket. While Git manages version control locally, such platforms provide additional features such as shared access to repositories, issue tracking, code reviews, and permission controls. They are widely used in software development projects, for both open-source software (OSS) and closed-source software projects.

On GitHub, a Git repo can be put in one of two spaces:

- A GitHub user account represents an individual user. It is created when you sign up for GitHub and includes a username, profile page, and personal settings. With a user account, you can create your own repositories, contribute to others’ projects, and manage collaboration settings for any repositories you own.

- A GitHub organisation (org for short) is a shared account used by a group such as a team, company, or open-source project. Organisations can own repositories and manage access to them through teams, roles, and permissions. Organisations are especially useful when managing repositories with shared ownership or when working at scale.

Every GitHub user must have a user account, even if they primarily work within an organisation.

PREPARATION: Create a GitHub account

Create a personal GitHub account as described in GitHub Docs → Creating an account on GitHub, if you don't have one yet.

Choose a sensible GitHub username as you are likely to use it for years to come in professional contexts e.g., in job applications.

[Optional, but recommended] Set up your GitHub profile, as explained in GitHub Docs → Setting up your profile.

Before you can interact with GitHub from your local Git client, you need to set up authentication. In the past, you could simply enter your GitHub username and password, but GitHub no longer accepts passwords for Git operations. Instead, you’ll use a more secure method — such as a Personal Access Token (PAT) or SSH keys — to prove your identity.

A Personal Access Token (PAT) is essentially a long, random string that acts like a password, but it can be scoped to specific permissions (e.g., read-only or full access) and revoked at any time. This makes it more secure and flexible than a traditional password.

Git supports two main protocols for communicating with GitHub: HTTPS and SSH.

- With HTTPS, you connect over the web and authenticate using your GitHub username and a Personal Access Token.

- With SSH, you connect using a cryptographic key pair you generate on your machine. Once you add your public key to your GitHub account, GitHub recognises your machine and lets you authenticate without typing anything further.

PREPARATION: Set up authentication with GitHub

Set up your computer's GitHub authentication, as described in the se-edu guide Setting up GitHub Authentication.

GitHub associates a commit to a user based on the email address in the commit metadata. When you push a commit, GitHub checks if the email matches a verified email on a GitHub account. If it does, the commit is shown as authored by that user. If the email doesn’t match any account, the commit is still accepted but won’t be linked to any profile.

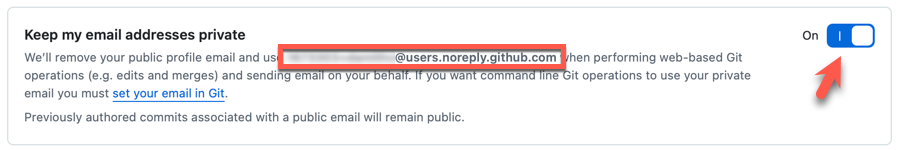

GitHub provides a no-reply email (e.g., 12345678+username@users.noreply.github.com) that you can use as your Git user.email to hide your real email while still associating commits with your GitHub account.

PREPARATION: [Optional] Configure user.email to use the no-reply email from GitHub

If you prefer not to include your real email address in commits, you can do the following:

Find your no-reply email provided by GitHub: Navigate to the email settings of your GitHub account and select the option to

Keep my email address private. The no-reply address will then be displayed, typically in the formatID+USERNAME@users.noreply.github.com.

Update your

user.emailwith that email address e.g.,git config --global user.email "12345678+username@users.noreply.github.com"

GitHub offers its own clients to make working with GitHub more convenient.

- The GitHub Desktop app provides a GUI for performing GitHub operations from your desktop, without needing to visit the GitHub web UI.

- The GitHub CLI (

gh) brings GitHub-specific commands to your terminal, letting you perform operations on GitHub from your command line.

If you are using Git-Mastery exercises (strongly recommended), you need to install and configure GitHub CLI because it is needed by Git-Mastery exercises involving GitHub.

PREPARATION: Set up GitHub CLI

1. Download and run the installer from the GitHub CLI releases page. This is the file named as GitHub CLI {version} windows {chip variant} installer.

1. Install GitHub CLI using Homebrew:

brew install gh

1. Install GitHub CLI, as explained in the GitHub CLI Linux installation guide for your distribution.

2. Authenticate yourself to GitHub account:

gh auth login

When prompted, choose the protocol (i.e., HTTPS or SSH) you used previously to set up your GitHub authentication.

3. Give GitHub CLI permission to delete repos in your account, as this is required for some of the Git-Mastery exercises.

gh auth refresh -s delete_repo

4. Verify the setup by checking the status of your GitHub CLI with your GitHub account.

gh auth status

You should see confirmation that you’re logged in.

5. Verify that Github and GitHub CLI is set up for Git-Mastery:

gitmastery check github

6. [Optional, Recommended] Ask Git-Mastery to switch on the 'progress sync' feature.

# cd into the gitmastery-exercises folder first

gitmastery progress sync on

What happens when you switch on the Git-Mastery 'progress sync' feature?

- Your Git-Mastery exercises progress will be backed up to your GitHub account. If you wipe out your local progress data by mistake, the remote copy will still be preserved.

- Git-Mastery will create a repo in your GitHub account, to back up your progress data. This repo will be publicly visible.

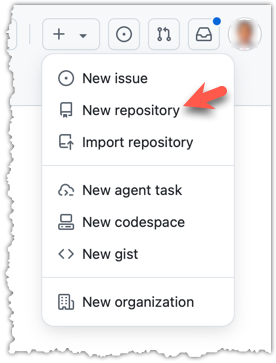

The first step of backing up a local repo on GitHub: create an empty repository on GitHub.

You can create a remote repository based on an existing local repository, to serve as a remote copy of your local repo. For example, suppose you created a local repo and worked with it for a while, but now you want to upload it onto GitHub. The first step is to create an empty repository on GitHub.

1 Login to your GitHub account and choose to create a new repo.

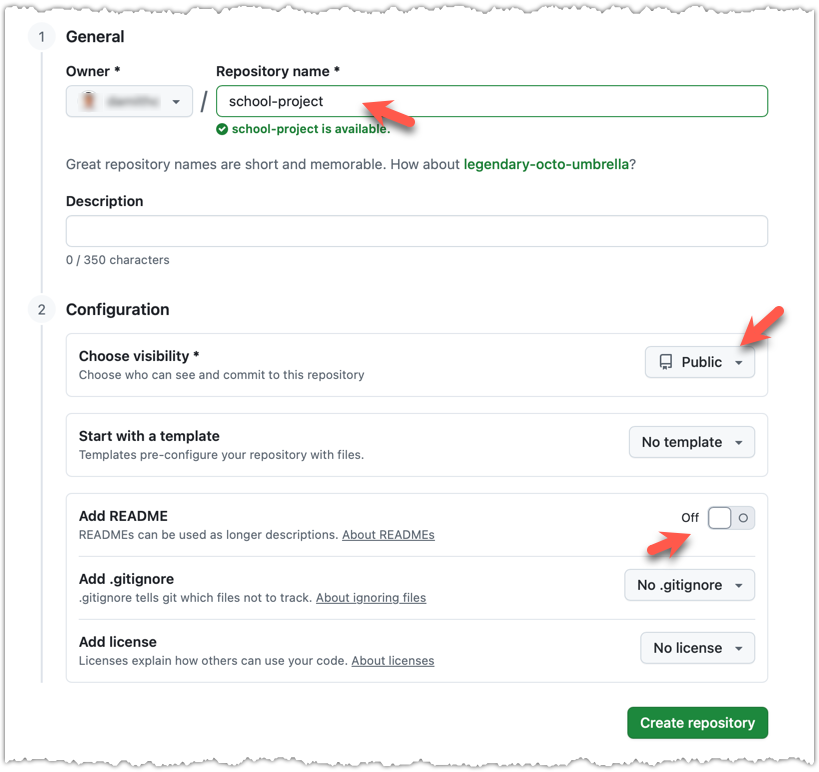

2 In the next screen, provide a name for your repo. Refer the screenshot below on some guidance on how to provide the required information.

Click Create repository button to create the new repository.

If you enable any of the three Add _____ options shown above, GitHub will not only create a repo, but will also initialise it with some initial content. That is not what we want here. To create an empty remote repo, keep those options disabled.

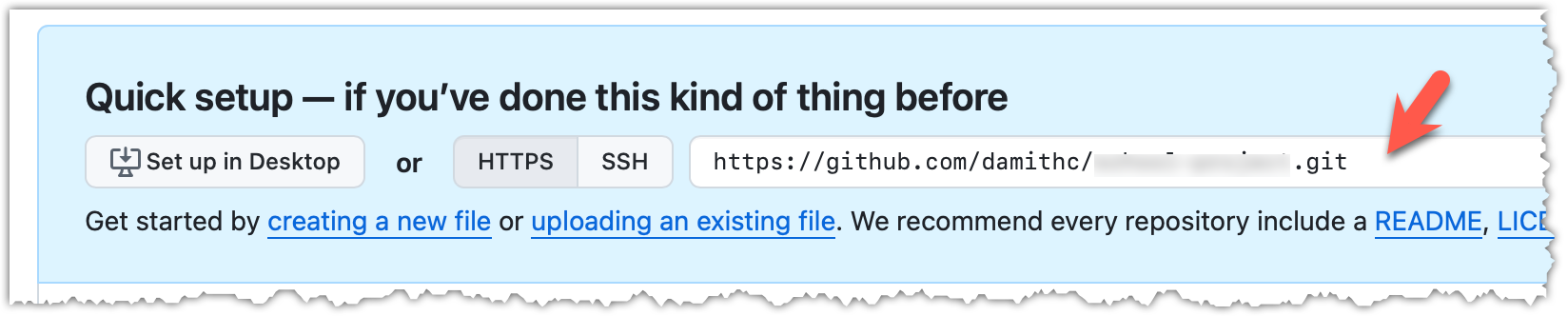

3 Note the URL of the repo. It will be of the form

https://github.com/{your_user_name}/{repo_name}.git.

e.g., https://github.com/johndoe/foobar.git (note the .git at the end)

done!

EXERCISE: remote-control

The second step of backing up a local repo on GitHub: link the local repo with the remote repo on GitHub.

A Git remote is a reference to a repository hosted elsewhere, usually on a server like GitHub, GitLab, or Bitbucket. It allows your local Git repo to communicate with another remote copy — for example, to upload locally-created commits that are missing in the remote copy.

By adding a remote, you are informing the local repo details of a remote repo it can communicate with, for example, where the repo exists and what name to use to refer to the remote.

The URL you use to connect to a remote repo depends on the protocol — HTTPS or SSH:

- HTTPS URLs use the standard web protocol and start with

https://github.com/(for GitHub users). e.g.,https://github.com/username/repo-name.git - SSH URLs use the secure shell protocol and start with

git@github.com:. e.g.,git@github.com:username/repo-name.git

A Git repo can have multiple remotes. You simply need to specify different names for each remote (e.g., upstream, central, production, other-backup ...).

Add the empty remote repo you created on GitHub as a remote of a local repo you have.

1 In a terminal, navigate to the folder containing the local repo things you created earlier.

2 List the current list of remotes using the git remote -v command, for a sanity check. No output is expected if there are no remotes yet.

3 Add a new remote repo using the git remote add <remote-name> <remote-url> command.

Format of the <remote-url>:

https://github.com/<owner>/<repo>.git # using HTTPS

git@github.com:<owner>/<repo>.git # using SSH

The full command:

git remote add origin https://github.com/JohnDoe/things.git # using HTTPS

git remote add origin git@github.com:JohnDoe/things.git # using SSH

4 List the remotes again to verify the new remote was added.

git remote -v

origin https://github.com/johndoe/things.git (fetch)

origin https://github.com/johndoe/things.git (push)

The same remote will be listed twice, to show that you can do two operations (fetch and push) using this remote. You can ignore that for now. The important thing is the remote you added is being listed.

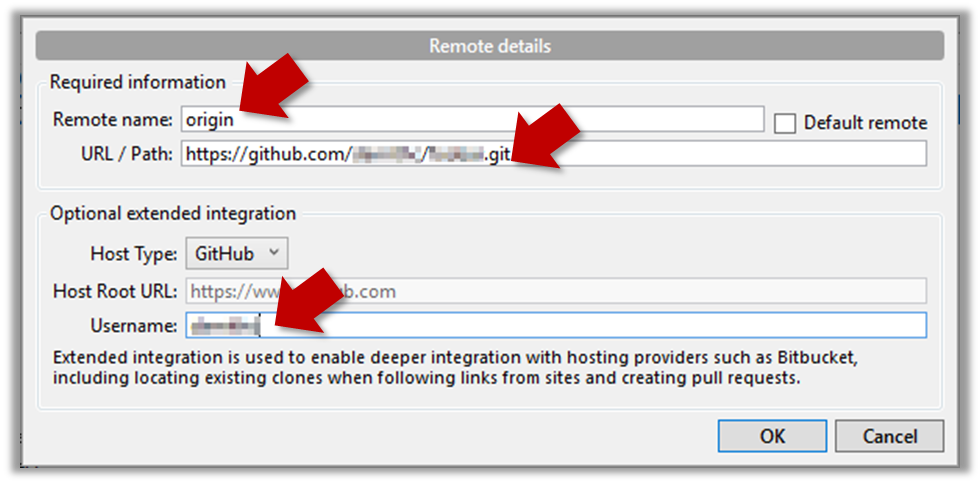

1 Open the local repo in Sourcetree.

2 Open the dialog for adding a remote, as follows:

Choose Repository → Repository Settings menu option.

Choose Repository → Repository Settings... → Choose Remotes tab.

3 Add a new remote to the repo with the following values.

Remote name: the name you want to assign to the remote repo i.e.,originURL/path: the URL of your remote repohttps://github.com/<owner>/<repo>.git # using HTTPS git@github.com:<owner>/<repo>.git # using SSHe.g.,

https://github.com/JohnDoe/things.git # using HTTPS git@github.com:JohnDoe/things.git # using SSHUsername: your GitHub username

4 Verify the remote was added by going to Repository → Repository Settings again.

5 Add another remote, to verify that a repo can have multiple remotes. You can use any name (e.g., backup and any URL for this).

done!

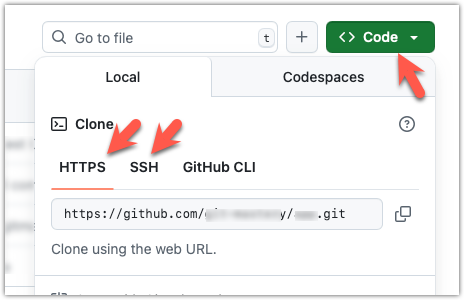

To find the URL of a repo on GitHub, you can click on the Code button:

EXERCISE: link-me

DETOUR: Managing Details of a Remote

To change the URL of a remote (e.g., origin), use git remote set-url <remote-name> <new-url> e.g.,

git remote set-url origin https://github.com/user/repo.git

To rename a remote, use git remote rename <old-name> <new-name> e.g.,

git remote rename origin upstream

To delete a remote from your Git repository, use git remote remove <remote-name> e.g.,

git remote remove origin

To check the current remotes and their URLs, use:

git remote -v

The third step of backing up a local repo on GitHub: push a copy of the local repo to the remote repo.

You can push content of one repository to another, usually from your local repo to a remote repo. Pushing transfers recorded Git history (such as past commits), but it does not transfer unstaged changes or untracked files.

- To push, you need to have to the remote repo.

- Pushing is performed one branch at a time; you must specify which branch you want to push.

You can configure Git to track a pairing between a local branch and a remote branch, so in future you can push from the same local branch to the corresponding remote branch without needing to specify them again. For example, you can set your local master branch to track the master branch on the remote repo origin i.e., local master branch will track the branch origin/master.

In the revision graph above, you see a new type of ref ( origin/master). This is a remote-tracking branch ref that represents the state of a corresponding branch in a remote repository (if you previously set up the branch to 'track' a remote branch). In this example, the master branch in the remote origin is also at the commit C3 (which means you have not created new commits after you pushed to the remote).

If you now create a new commit C4, the state of the revision graph will be as follows:

Explanation: When you create C4, the current branch master moves to C4, and HEAD moves along with it. However, the master branch in the remote origin remains at C3 (because you have not pushed C4 yet). That is, the remote-tracking branch origin/master is one commit behind the local branch master (or, the local branch is one commit ahead). The origin/master ref will move to C4 only after you push your local branch to the remote again.

Preparation Use a local repo that is connected to an empty remote repo e.g., the things repo from previous hands-on practicals:

1 Push the master branch to the remote. Also instruct Git to track this branch pair.

Use the git push -u <remote-repo-name> <local-branch-name> to push the commits to a remote repository.

git push -u origin master

Explanation:

push: the Git sub-command that pushes the current local repo content to a remote repoorigin: name of the remotemaster: branch to push-u(or--set-upstream): the flag that tells Git to track that this localmasteris trackingorigin/masterbranch

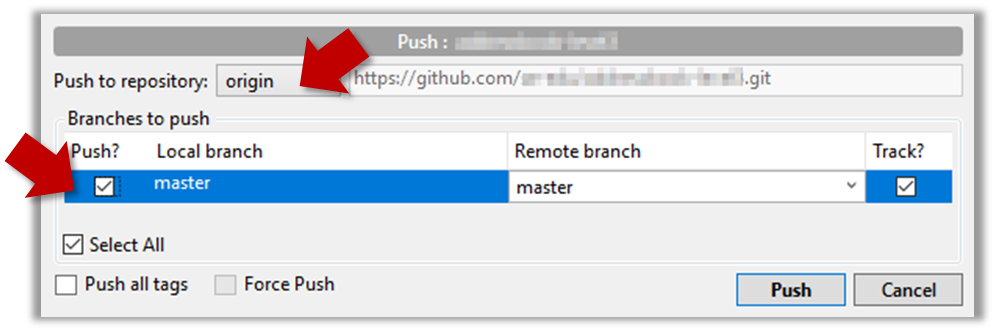

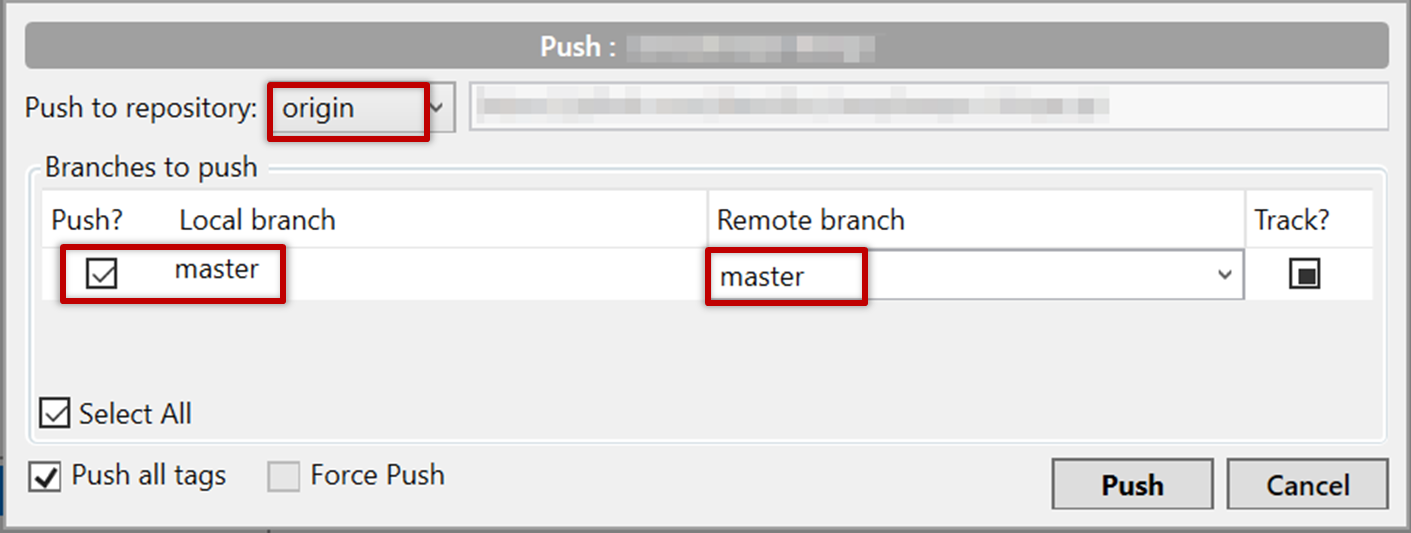

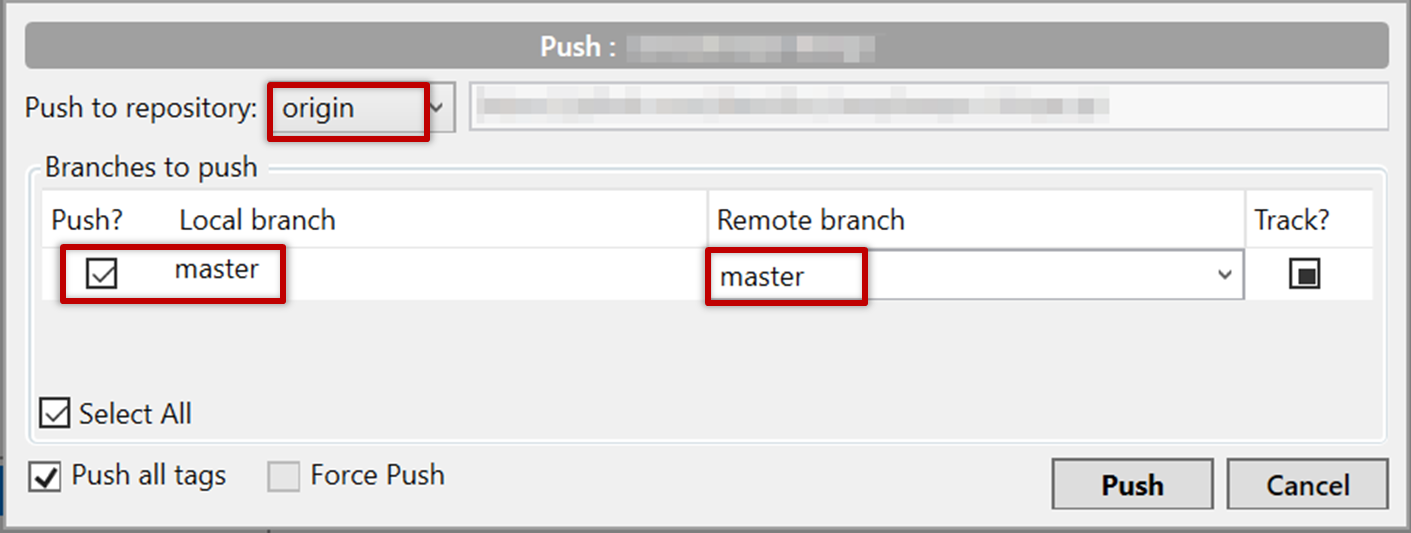

Click the Push button on the buttons ribbon at the top.

In the next dialog, ensure the settings are as follows, ensure the Track option is selected, and click the Push button on the dialog.

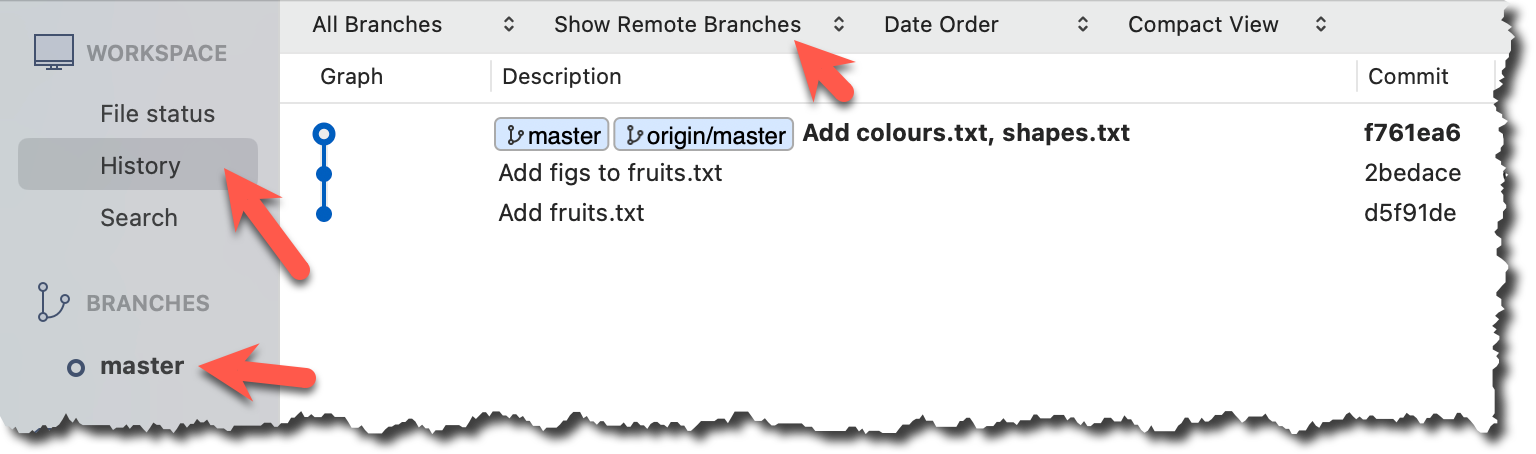

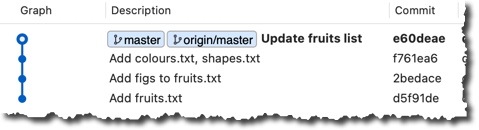

2 Observe the remote-tracking branch origin/master is now pointing at the same commit as the master branch.

Use the git log --oneline --graph to see the revision graph.

* f761ea6 (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

* 2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

* d5f91de Add fruits.txt

Click the History to see the revision graph.

- In some versions of Sourcetree, the

HEADref may not be shown -- it is implied that theHEADref is pointing to the same commit the currently active branch ref is pointing. - If the remote-tracking branch ref (e.g.,

origin/master) is not showing up, you may need to enable theShow Remote Branchesoption.

done!

The push command can be used repeatedly to send further updates to another repo e.g., to update the remote with commits you created since you pushed the first time.

Target Add a commit to the same local repo, and push it to the remote repo.

1 Commit some changes in your local repo. Example:

echo "Elderberries" >> fruits.txt

git commit -am "Update fruits list"

Use the git commit command to create commits, as you did before.

Optionally, you can run the git status command, which should confirm that your local branch is 'ahead' by one commit (i.e., the local branch has commits that are not present in the corresponding branch in the remote repo).

git status

On branch master

Your branch is ahead of 'origin/master' by 1 commit.

(use "git push" to publish your local commits)

nothing to commit, working tree clean

You can also use the git log --oneline --graph command to see where the branch refs are. Note how the remote-tracking branch origin/master is one commit behind the local master.

e60deae (HEAD -> master) Update fruits list

f761ea6 (origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

Create commits as you did before.

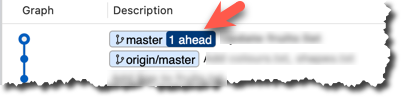

Before pushing the new commit, Sourcetree will indicate that your local branch is 'ahead' by one commit (i.e., the local branch has one new commit that is not in the corresponding branch in the remote repo).

2 Push the new commits to your fork on GitHub.

To push the newer commit(s) in the current branch master to the remote origin, you can use any of the following commands:

git push origin mastergit push origin

→ Git will assume you are pushing the current branch (e.g.,master) even if you don't specify it.git push

→ Git will assume you are pushing the current branch (e.g.,master). Due to tracking you've set up earlier, Git will assume that you want to push it to the matching branch onorigin.

After pushing, the revision graph should look something like the following (note how both local and remote-tracking branch refs are pointing to the same commit again).

e60deae (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Update fruits list

f761ea6 Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

To push, click the Push button on the top buttons ribbon, ensure the settings are as follows in the next dialog, and click the Push button on the dialog.

After pushing the new commit to the remote, the remote-tracking branch ref should move to the new commit:

done!

Note that you can push between two repos only if those repos have a shared history among them (i.e., one should have been created by copying the other).

EXERCISE: push-over

DETOUR: Pushing to Multiple Repos

You can push to any number of repos, as long as the target repos and your repo have a shared history.

- Add the GitHub repo URL as a remote while giving a suitable name (e.g.,

upstream,central,production,backup...), if you haven't done so already. - Push to the target repo -- remember to select the correct target repo when you do.

e.g., git push backup master

Git allows you to specify which files should be omitted from revision control.

You can specify which files Git should ignore from revision control. While you can always omit files from revision control simply by not staging them, having an 'ignore-list' is more convenient, especially if there are files inside the working folder that are not suitable for revision control (e.g., temporary log files) or files you want to prevent from accidentally including in a commit (files containing confidential information).

A repo-specific ignore-list of files can be specified in a .gitignore file, stored in the root of the repo folder.

The .gitignore file itself can be either revision controlled or ignored.

- To version control it (the more common choice – which allows you to track how the

.gitignorefile changes over time), simply commit it as you would commit any other file. - To ignore it, simply add its name to the

.gitignorefile itself.

The .gitignore file supports file patterns e.g., adding temp/*.tmp to the .gitignore file prevents Git from tracking any .tmp files in the temp directory.

SIDEBAR: .gitignore File Syntax

Blank lines: Ignored and can be used for spacing.

Comments: Begin with

#(lines starting with # are ignored).# This is a commentWrite the name or pattern of files/directories to ignore.

log.txt # Ignores a file named log.txtWildcards:

*matches any number of characters, except/(i.e., for matching a string within a single directory level):abc/*.tmp # Ignores all .tmp files in abc directory**matches any number of characters (including/)**/foo.tmp # Ignores all foo.tmp files in any directory?matches a single characterconfig?.yml # Ignores config1.yml, configA.yml, etc.[abc]matches a single character (a, b, or c)file[123].txt # Ignores file1.txt, file2.txt, file3.txt

Directories:

- Add a trailing

/to match directories.logs/ # Ignores the logs directory - Patterns without

/match files/folders recursively.*.bak # Ignores all .bak files anywhere - Patterns with

/are relative to the.gitignorelocation./secret.txt # Only ignores secret.txt in the root directory

- Add a trailing

Negation: Use

!at the start of a line to not ignore something.*.log # Ignores all .log files !important.log # Except important.log

Example:

# Ignore all log files

*.log

# Ignore node_modules folder

node_modules/

# Don’t ignore main.log

!main.log

1 Add a file into your repo's working folder that you presumably do not want to revision-control e.g., a file named temp.txt. Observe how Git has detected the new file.

Add a few other files with .tmp extension.

2 Configure Git to ignore those files:

Create a file named .gitignore in the working directory root and add the text temp.txt into it.

echo "temp.txt" >> .gitignore

temp.txt

Observe how temp.txt is no longer detected as 'untracked' by running the git status command (but now it will detect the .gitignore file as 'untracked'.

Update the .gitignore file as follows:

temp.txt

*.tmp

Observe how .tmp files are no longer detected as 'untracked' by running the git status command.

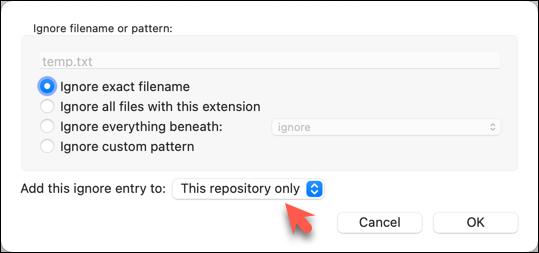

The file should be currently listed under Unstaged files. Right-click it and choose Ignore.... Choose Ignore exact filename(s) and click OK.

Also take note of other options available e.g., Ignore all files with this extension etc. They may be useful in future.

Note how the temp.text is no longer listed under Unstaged files. Observe that a file named .gitignore has been created in the working directory root and has the following line in it. This new file is now listed under Unstaged files.

temp.txt

Right-click on any of the .tmp files you added, and choose Ignore... as you did previously. This time, choose the option Ignore files with this extension.

Note how .temp files are no longer shown as unstaged files, and the .gitignore file has been updated as given below:

temp.txt

*.tmp

3 Optionally, stage and commit the .gitignore file.

done!

Files recommended to be omitted from version control

- Binary files generated when building your project e.g.,

*.class,*.jar,*.exe

Reasons:- no need to version control these files as they can be generated again from the source code

- Revision control systems are optimized for tracking text-based files, not binary files.

- Temporary files e.g., log files generated while testing the product

- Local files i.e., files specific to your own computer e.g., local settings of your IDE (

.idea/) - Sensitive content i.e., files containing sensitive/personal information e.g., credential files, personal identification data (especially if there is a possibility of those files getting leaked via the revision control system).

EXERCISE: ignoring-somethings

DETOUR: Ignoring Previously-Tracked Files

Adding a file to the .gitignore file is not enough if the file was already being tracked by Git in previous commits. In such cases, you need to do both of the following:

- Untrack the file (i.e., remove the file from the staging area and stop tracking it in future), using the

git rm --cached <file(s)>command.git rm --cached data/ic.txt - Add it to the

.gitignorefile, as usual.

At this point: You should now be able to create a copy of your repo on GitHub, and keep it updated as you add more commits to your local repo. If something goes wrong with your local repo (e.g., disk crash), you can now recover the repo using the remote repo (this tour did not cover how exactly you can do that -- it will be covered in a future tour).

What's next: Tour 3: Working Off a Remote Repo