Target Usage: To use Git to systematically record the history of a folder in your own computer. More specifically, to use Git to save a snapshot of the folder at specific points of time.

Motivation: Recording the history of files in a folder (e.g, code files of a software project, case notes, files related to an article/book that you are authoring) can be useful in case you need to refer to past versions.

Lesson plan:

T1L1. Introduction to Revision Control covers that part.

T1L2. Preparing to Use Git covers that part.

T1L3. Putting a Folder Under Git's Control covers that part.

T1L4. Specifying What to Include in a Snapshot covers that part.

T1L5. Saving a Snapshot covers that part.

T1L6. Examining the Revision History covers that part.

Before learning about Git, let us first understand what revision control is.

Given below is a general introduction to revision control, adapted from bryan-mercurial-guide:

Revision control is the process of managing multiple versions of a piece of information. In its simplest form, this is something that many people do by hand: every time you modify a file, save it under a new name that contains a number, each one higher than the number of the preceding version.

Manually managing multiple versions of even a single file is an error-prone task, though, so software tools to help automate this process have long been available. The earliest automated revision control tools were intended to help a single user to manage revisions of a single file. Over the past few decades, the scope of revision control tools has expanded greatly; they now manage multiple files, and help multiple people to work together. The best modern revision control tools have no problem coping with thousands of people working together on projects that consist of hundreds of thousands of files.

There are a number of reasons why you or your team might want to use an automated revision control tool for a project.

- It will track the history and evolution of your project, so you don't have to. For every change, you'll have a log of who made it; why they made it; when they made it; and what the change was.

- It makes it easier for you to collaborate when you're working with other people. For example, when people more or less simultaneously make potentially incompatible changes, the software will help you to identify and resolve those conflicts.

- It can help you to recover from mistakes. If you make a change that later turns out to be an error, you can revert to an earlier version of one or more files. In fact, a good revision control tool will even help you to efficiently figure out exactly when a problem was introduced.

- It will help you to work simultaneously on, and manage the drift between, multiple versions of your project.

Most of these reasons are equally valid, at least in theory, whether you're working on a project by yourself, or with a hundred other people.

A revision is the state of a piece of information at a specific point in time, resulting from changes made to it e.g., if you modify the code and save the file, you have a new revision (or a new version) of that file. Some seem to use this term interchangeably with version while others seem to distinguish the two -- here, let us treat them as the same, for simplicity.

Revision Control Software (RCS) are the software tools that automate the process of Revision Control i.e., managing revisions of software . RCS are also known as Version Control Software (VCS), and by a few other names.

Git is the most widely used RCS today. Other RCS tools include Mercurial, Subversion (SVN), Perforce, CVS (Concurrent Versions System), Bazaar, TFS (Team Foundation Server), and Clearcase.

Github is a web-based project hosting platform for projects using Git for revision control. Other similar services include GitLab, BitBucket, and SourceForge.

Before you start learning Git, you need to install some tools on your computer.

Installing Git

Git is a free and open source software used for revision control. To use Git, you need to install Git on your computer.

PREPARATION: Install Git

Download the Git installer from the official Git website.

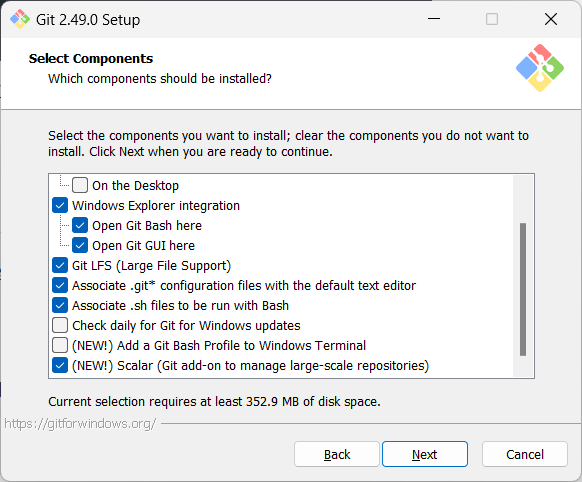

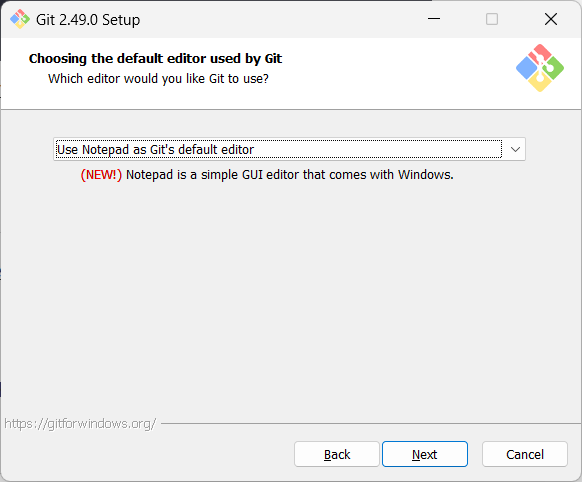

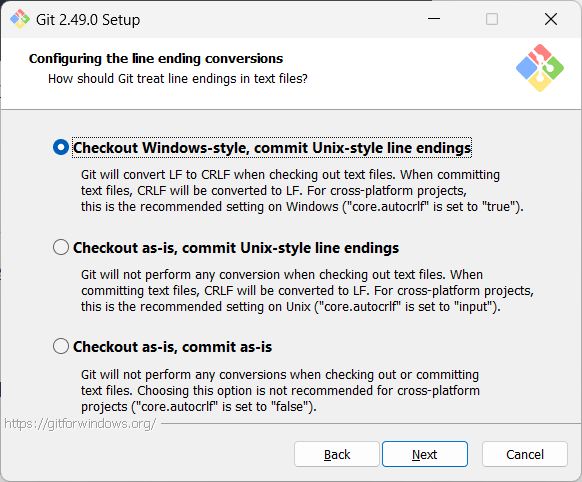

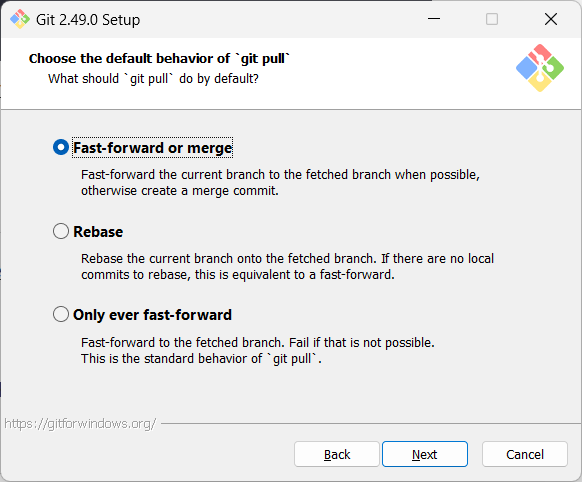

Run the installer and make sure to select the option to install Git Bash when prompted.

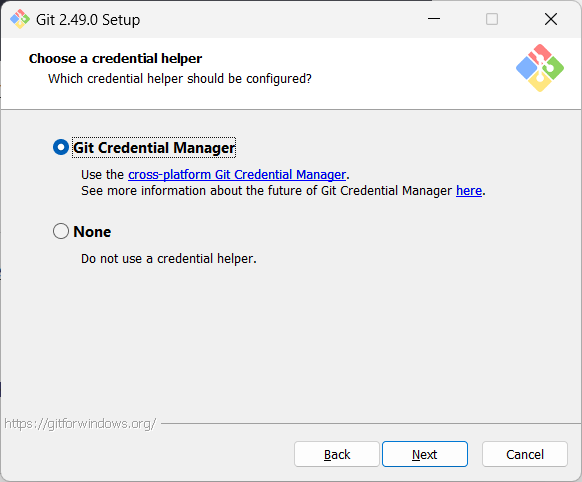

Screenshots given below provide some guidance on the dialogs you might encounter when installing Git. In other cases, go with the default option.

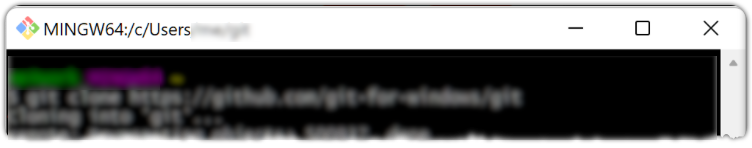

When running Git commands, we recommend Windows users to use the Git Bash terminal that comes with Git. To open Git Bash terminal, hit the key and type git-bash.

It may be possible that the installation didn't add a shortcut to the Start Menu.

You can navigate to the directory where git-bash.exe is (most likely C:\Program Files\Git\git-bash.exe), double click git-bash.exe to open Git Bash.

You can also right-click it and choose Pin to Start or Pin to taskbar.

SIDEBAR: Git Bash Terminal

Git Bash is a terminal application that lets you use Git from the command line on Windows. Since Git was originally developed for Unix-like systems (like Linux and macOS), Windows does not come with a native shell that supports all the commands and utilities commonly used with Git.

Git Bash provides a Unix-like command-line environment on Windows. It includes:

- A Bash shell (Bash stands for Bourne Again SHell), which is a widely used command-line interpreter on Linux and macOS.

- Common Unix tools and commands (like

ls,cat,ssh, etc.) that are useful when working with Git and scripting.

When copy-pasting text onto a Git Bash terminal, you will not be able to use the familiar Ctrl+V key combo to paste. Instead, right-click on the terminal and use the Paste menu option.

On Windows, you might need to close and open the terminal again for it to recognise changes done elsewhere in the computer (e.g., newly-installed software, changes to system variables, etc.).

Use your Linux distribution's package manager to install Git. Examples:

Debian/Ubuntu, run

sudo apt-get updateand thensudo apt-get install git.Fedora: run

sudo dnf updateand thensudo dnf install git.

Verify Git is installed, by running the following command in a terminal.

git --version

git version 2._._

The output should display the version number.

Configuring user.name and user.email

Git needs to know who you are to record changes properly. When you save a snapshot of your work in Git, it records your name and email as the author of that change. This ensures everyone working on the project can see who made which changes. Accordingly, you should set the config settings user.name and user.email before you start Git for revision control.

PREPARATION: Set user.name and user.email

To set the two config settings, run the following commands in your terminal window:

git config --global user.name "<your-name>"

git config --global user.email "<your-email@example.com>"

To check if they are set as intended, you can use the following two commands:

git config --global user.name

git config --global user.email

Interacting with Git: CLI vs GUI

Git is fundamentally a command-line tool. You primarily interact with it through its by typing commands. This gives you full control over its features and helps you understand what’s really happening under the hood.

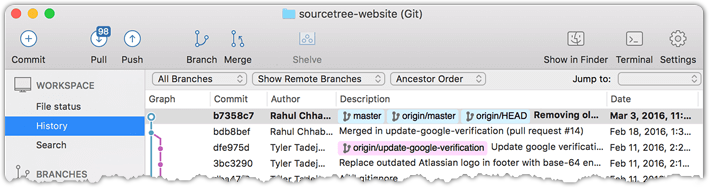

clients for Git also exist, such as Sourcetree, GitKraken, and the built-in Git support in editors like Intellij IDEA and VS Code. These tools provide a more visual way to perform some Git operations.

If you're new to Git, it's best to learn the CLI first. The CLI is universal, always available (even on servers), and helps you build a solid understanding of Git’s concepts. You can use GUI clients as a supplement — for example, to visualise complex history structures.

Mastering the CLI gives you confidence and flexibility, while GUI tools can serve as helpful companions.

PREPARATION: [Optional] Install a GUI client

Optionally, you can install a Git GUI client. e.g., Sourcetree (installation instructions).

Our Git lessons show how to perform Git operations in Git CLI, and in Sourcetree -- the latter just to illustrate how Git GUIs work. It is perfectly fine for you to learn the CLI only.

[image credit: https://www.sourcetreeapp.com]

Installing the Git-Mastery App

In these lessons, we are piloting a new companion app called Git-Mastery that we have been developing to help Git learners. Specifically, it provides exercises that you can do to self-test your Git knowledge, and the app will also verify if your solution is correct.

If you are new to Git, we strongly recommend that you install and use the Git-Mastery app.

PREPARATION: [Recommended] Install and Configure the Git-Mastery App

1. Install the Git-Mastery App

- a)Download the

.exefile from the latest release. - b)Add the folder containing the

.exeto your Windows System VariablePATH, by following this guide.

E.g. If the file location isC:\Users\Jane\Tools\gitmastery.exe, you should addC:\Users\Jane\Toolsto yourPATH. - c)Close and reopen the Git Bash terminal (for the updated

PATHto take effect).

Windows Defender says gitmastery.exe is a virus?

In some cases, Windows Defender virus scanner can incorrectly block gitmastery.exe as a virus. The Git-Mastery team is currently working on getting the app white-listed. In the meantime, it is safe to override the warning/blockade, either by choosing Run anyway option (if given) or using the following steps.

- Open

Windows Security→Virus & threat protection. - Click

Protection history. - Find the blocked

gitmastery.exeand click it. - Choose

Actions→Allow on device.

After this step, you may need to re-download the file if it was removed previously.

Alternatively, refer to this page to see how to exclude a file from Windows virus scanner (look for the section named 'Exclusions').

brew tap git-mastery/gitmastery

brew install gitmastery

Ensure you are running libc version 2.38 or newer (you can use the ldd --version command to check the current version).

Then install the app by running the following commands:

echo "deb [trusted=yes] https://git-mastery.github.io/gitmastery-apt-repo any main" | \

sudo tee /etc/apt/sources.list.d/gitmastery.list > /dev/null

sudo apt install software-properties-common

sudo add-apt-repository "deb https://git-mastery.github.io/gitmastery-apt-repo any main"

sudo apt update

sudo apt-get install gitmastery

Use an AUR helper to install gitmastery-bin. For example using yay:

yay -S gitmastery-bin

Alternatively, you can build the PKGBUILD yourself following the instructions on the Arch wiki.

If you are using a Linux distribution that is not yet supported by Git-Mastery, please download the right binary for your architecture from the latest release.

Install it to /usr/bin to access the binary, the following using version 3.3.0 as an example.

install -D -m 0755 gitmastery-3.3.0-linux-arm64 /usr/bin/gitmastery

2. To verify the installation, run the gitmastery --help command from a couple of different folder locations. An example given below (IMPORTANT: change the cd command to match your folders):

gitmastery --help

cd ../my-projects # cd into a different folder

gitmastery --help

The current version of the app takes about 3-5 seconds to respond to a command. This is because the app comes with a bundled Python runtime (so that users don't need to install Python first) which needs to load first before the command can be executed.

3. Trigger the initial setup by running the gitmastery setup command in a suitable folder (the app will create files/folders inside this folder).

mkdir gitmastery-home

cd gitmastery-home

gitmastery setup

The gitmastery setup command will perform the following tasks:

- a)Checks if Git is installed.

- b)Checks if

user.nameanduser.emailare set. - c)Prompts you to specify a name for the git-mastery exercises directory

- Recommended: accept the default (i.e.,

gitmastery-exercises) by pressing Enter. - If you choose to specify a different name for that folder, remember to use that name instead whenever our instructions refer to the

gitmastery-exercisesfolder.

- Recommended: accept the default (i.e.,

- d)Sets up a mechanism to locally track the progress of your exercises.

Notes:

- If the command failed due to checks (a) or (b) failing, you can rectify the problem and run the command again.

- If you wish to check the Git set up again at a later time, you can run the

gitmastery check gitcommand.

4. Keep the app updated. As the Git-Mastery app is under active development, it is likely to get updated several times during the semester. When you run a gitmastery <command>, the output will warn you if there is a new version, in which case you should update the app immediately, by following the instructions in that message.

Instructions for updating the Git-Mastery app are here.

To be able to save snapshots of a folder using Git, you must first put the folder under Git's control by initialising a Git repository in that folder.

Normally, we use Git to manage a revision history of a specific folder, which gives us the ability to revision-control any file in that folder and its subfolders.

To put a folder under the control of Git, we initialise a repository (short name: repo) in that folder. This way, we can initialise repos in different folders, to revision-control different clusters of files independently of each other e.g., files belonging to different projects.

You can follow the hands-on practical below to learn how to initialise a repo in a folder.

What is this? HANDS-ON panels contain hands-on activities you can do as you learn Git. If you are new to Git, we strongly recommend that you do them yourself (even if they appear straightforward), as hands-on usage will help you internalise the concepts and operations better.

Preparation Choose a folder to put under Git's control. The folder may or may not contain any files. For this practical, let us create a folder named things for this purpose.

You can get the Git-Mastery app to for doing this practical, or create the sandbox manually. Instructions for the both options are given below.

To prepare the sandbox for this practical:

- i.Navigate inside the

gitmastery-exercisesfolder. - ii.Run

gitmastery download hp-init-repocommand.

The sandbox will be set up inside the gitmastery-exercises/hp-init-repo folder.

Assuming you have a folder named git-practicals that you wish to use for doing Git hands-on practicals in, you can run the following commands.

cd git-practicals

mkdir things

Avoid putting Git repos inside cloud-synced (e.g., OneDrive, Dropbox) folders. Reason: Multiple tools trying to detect/sync changes in the same folder can cause conflicts and unexpected behaviors.

If you want to access project files from multiple computers, use Git to do that (rather than cloud syncing tools).

1 Then cd into it.

cd things

2 Run the git status command to check the status of the folder.

git status

fatal: not a git repository (or any of the parent directories): .git

Don't panic. The error message is expected. It confirms that the folder currently does not have a Git repo.

3 Now, initialise a repository in that folder.

Use the command git init which should initialise the repo.

git init

Initialized empty Git repository in things/.git/

The output might also contain a hint about a name for an initial branch (e.g., hint: Using 'master' as the name for the initial branch ...). You can ignore that for now.

Note how the output mentions the repo being created in things/.git/ (not things/). More on that later.

-

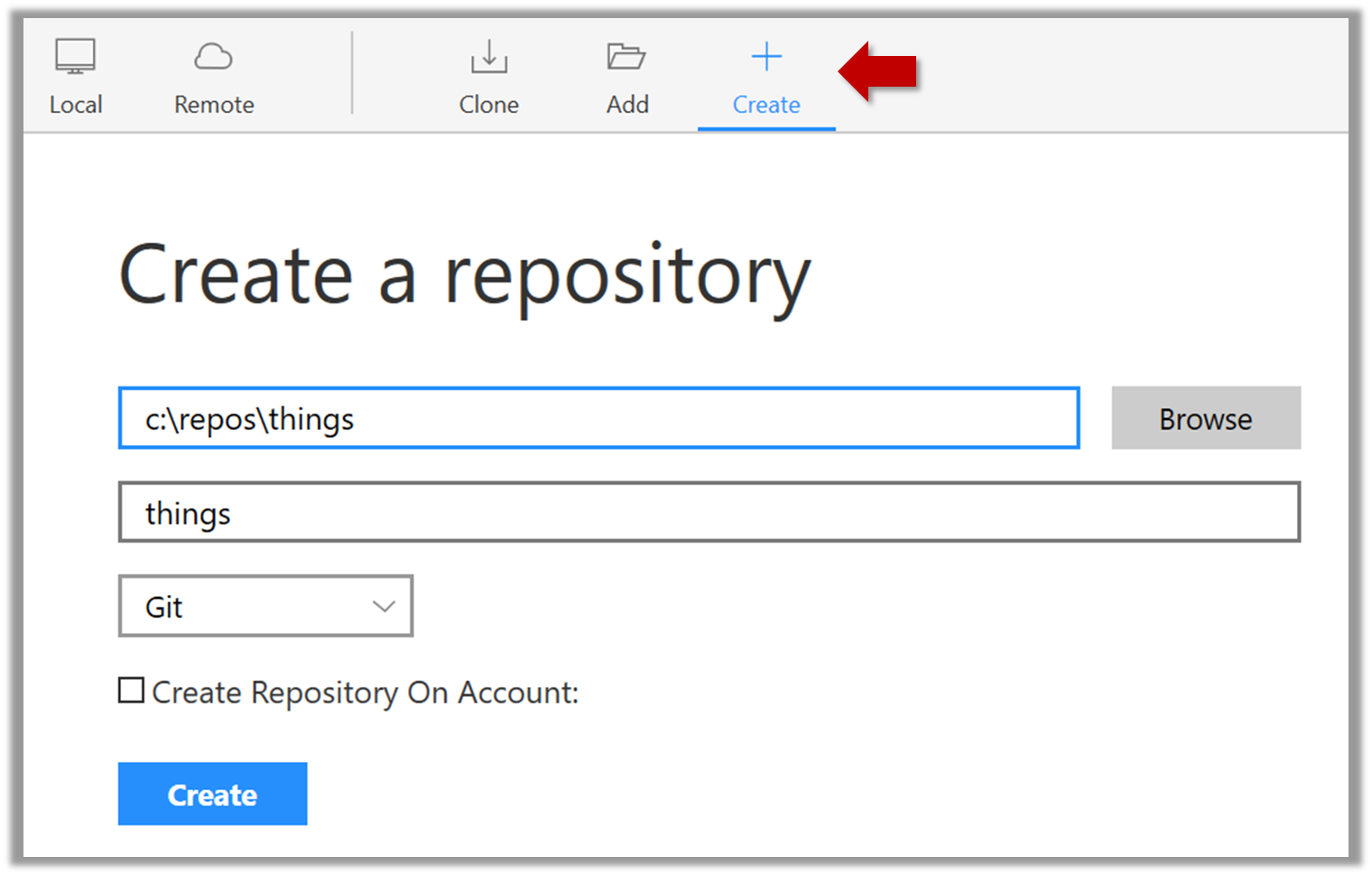

Windows: Click

File→Clone/New…→ Click on+ Createbutton on the top menu bar.

Enter the location of the directory and clickCreate. -

Mac:

New...→Create Local Repository(orCreate New Repository) → Click...button to select the folder location for the repository → click theCreatebutton.

done!

Initialising a repo results in two things:

- a)First, Git now recognises this folder as a Git repository, which means it can now help you track the version history of files inside this folder.

To confirm, you can run the git status command. It should respond with something like the following:

git status

On branch master

No commits yet

nothing to commit (create/copy files and use "git add" to track)

Don't worry if you don't understand the output (we will learn about them later); what matters is that it no longer gives an error message as it did before.

done!

- b)Second, Git created a hidden subfolder named

.gitinside thethingsfolder. This folder will be used by Git to store metadata about this repository.

A Git-controlled folder is divided into two main parts:

- The repository – stored in the hidden

.gitsubfolder, which contains all the metadata and history. - The working directory – everything else in that folder, where you create and edit files.

What is this? EXERCISE panels contain a Git-Mastery exercise that you can download using the Git-Mastery app, and you can use the same app to verify that your solution is correct.

EXERCISE: under-control

What is this? DETOUR panels contain related directions you can optionally explore. We recommend that you only skim them the first time you are going through a tour (i.e., just to know what each detour covers); you can revisit them later, to deepen your knowledge further, or when you encounter a use case related to the concepts covered by the detour.

DETOUR: Undoing a Repo Initialisation

When Git initialises a repo in a folder, it does not touch any files in the folder, other than create the .git folder its contents. So, reversing the operation is as simple as deleting the newly-created .git folder.

git status #run this to confirm a repo exists

rm -rf .git #delete the .git folder

git status #this should give an error, as the repo no longer exists

To save a snapshot, you start by specifying what to include in it, also called staging.

Git considers new files that you add to the working directory as 'untracked' i.e., Git is aware of them, but they are not yet under Git's control. The same applies to files that existed in the working folder at the time you initialised the repo.

A Git repo has an internal space called the staging area which it uses to build the next snapshot. Another name for the staging area is the index.

We can stage an untracked file to tell Git that we want its current version to be included in the next snapshot (in Git terminology, such a snapshot is called a commit). Once you stage an untracked file, it becomes 'tracked' (i.e., under Git's control). A staged file can be unstaged to indicate that we no longer want it to be included in the next snapshot.

In the example below, you can see how staging files change the status of the repo as you go from (a) to (c).

staging area

[empty]

other metadata ...

├─ fruits.txt (untracked!)

└─ colours.txt (untracked!)

(a) State of the repo, just after initialisation, and creating two files. Both are untracked.

staging area

└─ fruits.txt

other metadata ...

├─ fruits.txt (tracked)

└─ colours.txt (untracked!)

(b) State after staging

fruits.txt.staging area

├─ fruits.txt

└─ colours.txt

other metadata ...

├─ fruits.txt (tracked)

└─ colours.txt (tracked)

(c) State after staging

colours.txt.preparation

You can continue using the sandbox created in the previous hands-on practical, or,

1 Add a file (e.g., fruits.txt) to the things repo folder.

Here is an easy way to do that with a single terminal command.

echo -e "apples\nbananas\ncherries" > fruits.txt

apples

bananas

cherries

Windows users: Use the git-bash terminal to run the above command (and all commands given in these lessons). Some of them might not work in other terminals such as the PowerShell.

To see the content of the file, you can use the cat command:

cat fruits.txt

2 Stage the new file.

2.1 Check the status of the folder using the git status command.

git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Untracked files:

(use "git add <file>..." to include in what will be committed)

fruits.txt

nothing added to commit but untracked files present (use "git add" to track)

2.2 Use the git add <file> command to stage the file.

git add fruits.txt

You can replace the add with stage (e.g., git stage fruits.txt) and the result is the same (they are synonyms).

Windows users: When using the echo command to write to text files from Git Bash, you might see a warning LF will be replaced by CRLF the next time Git touches it when Git interacts with such a file. This warning is caused by the way line endings are handled differently by Git and Windows. You can simply ignore it, or suppress it in future by running the following command:

git config --global core.safecrlf false

2.3 Check the status again. You can see the file is no longer 'untracked'.

git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: fruits.txt

As before, don't worry if you don't understand the content of the output (we'll unpack it in a later lesson). The point to note is that the file is no longer listed as 'untracked'.

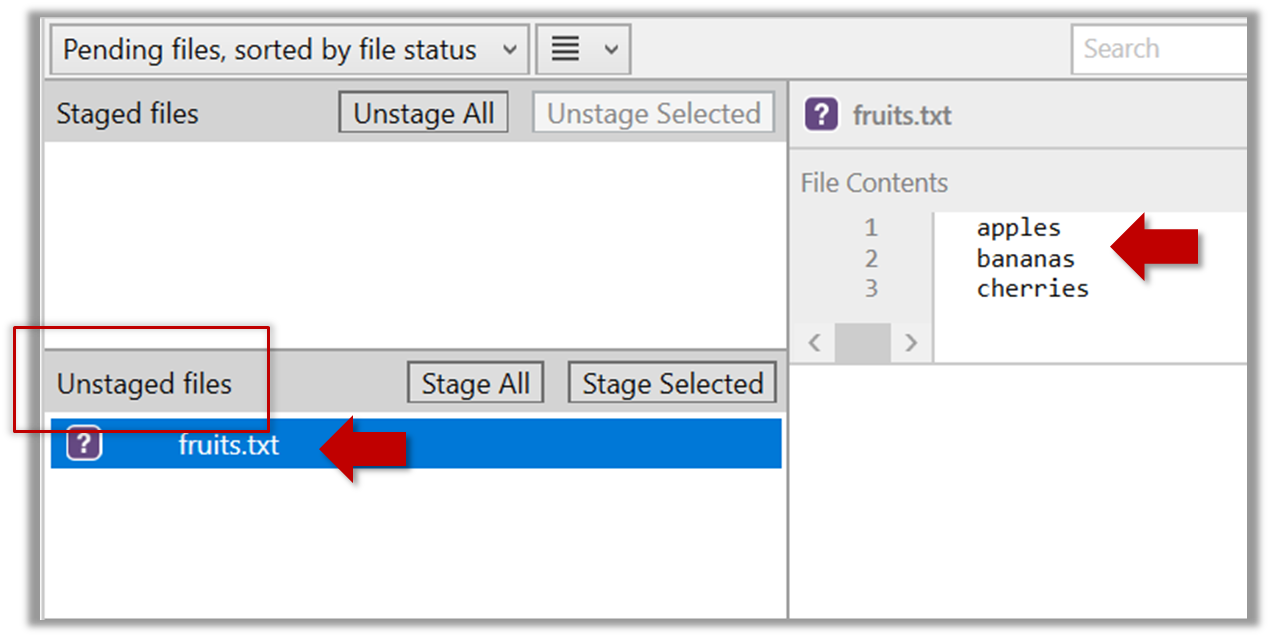

2.1 Note how the file is shown as ‘unstaged’. The question mark icon indicates the file is untracked.

If the newly-added file does not show up in Sourcetree UI, refresh the UI (: F5

| ⌥+R)

Sourcetree screenshots/instructions: vs

Note that Sourcetree UI can vary slightly between Windows and Mac versions. Some of the screenshots given in our lessons are from the Windows version while some are from the Mac version.

In som cases, we have specified how they differ.

In other cases, you may need to adapt if the given screenshots/instructions are slightly different from what you are seeing in your Sourcetree.

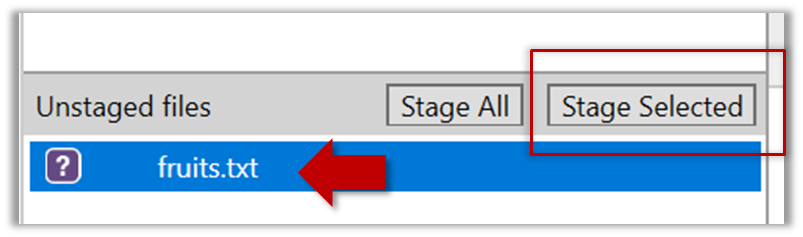

2.2 Stage the file:

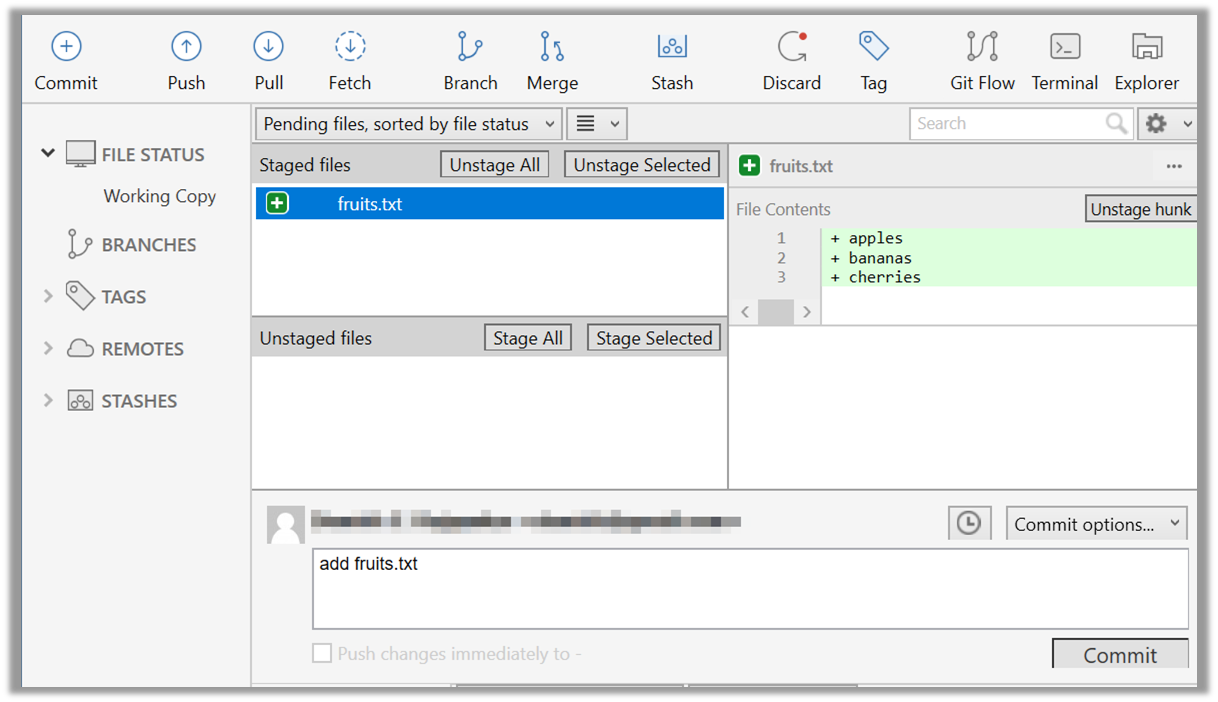

Select the fruits.txt and click on the Stage Selected button.

Staging can be done using tick boxes or the ... menu in front of the file.

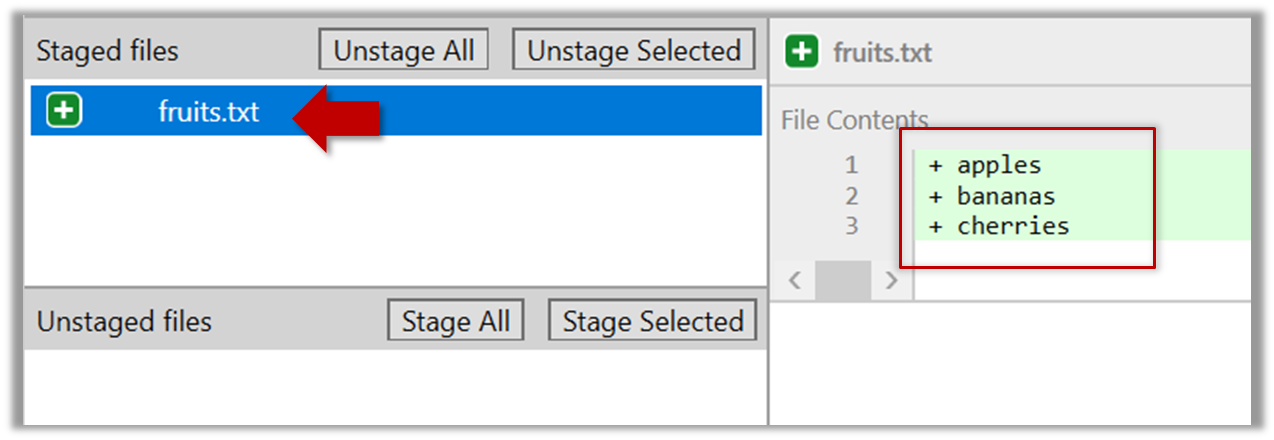

2.3 Note how the file is staged now i.e., fruits.txt appears in the Staged files panel now.

If Sourcetree shows a \ No newline at the end of the file message below the staged lines (i.e., below the cherries line in the above screenshot), that is because you did not hit enter after entering the last line of the file (hence, Git is not sure if that line is complete). To rectify, move the cursor to the end of the last line in that file and hit enter (like you are adding a blank line below it). This new change will now appear as an 'unstaged' change. Stage it as well.

done!

If you modify a staged file, it goes into the 'modified' state i.e., the file contains modifications that are not present in the copy that is waiting (in the staging area) to be included in the next snapshot. If you wish to include these new changes in the next snapshot, you need to stage the file again, which will overwrite the copy of the file that was previously in the staging area.

The example below shows how the status of a file changes when it is modified after it was staged.

staging area

Alice

other metadata ...

Alice

(a) The file names.txt is staged. The copy in the staging area is an exact match to the one in the working directory.

staging area

Alice

other metadata ...

Alice

Bob

(b) State after adding a line to the file. Git indicates it as 'modified' because it now differs from the version in the staged area.

staging area

Alice

Bob

other metadata ...

Alice

Bob

(c) After staging the file again, the staging area is updated with the latest copy of the file, and it is no longer marked as 'modified'.

preparation

You can continue using the sandbox created in the previous hands-on practical, or,

1 First, add another line to fruits.txt, to make it 'modified'.

Here is a way to do that with a single terminal command.

echo "dragon fruits" >> fruits.txt

apples

bananas

cherries

dragon fruits

2 Now, verify that Git sees that file as 'modified'.

Use the git status command to check the status of the working directory.

$ git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: fruits.txt

Changes not staged for commit:

(use "git add <file>..." to update what will be committed)

(use "git restore <file>..." to discard changes in working directory)

modified: fruits.txt

Note how fruits.txt now appears twice, once as new file: ... (representing the version of the file we staged earlier, which had only three lines) and once as modified: ... (representing the latest version of the file which now has a fourth line).

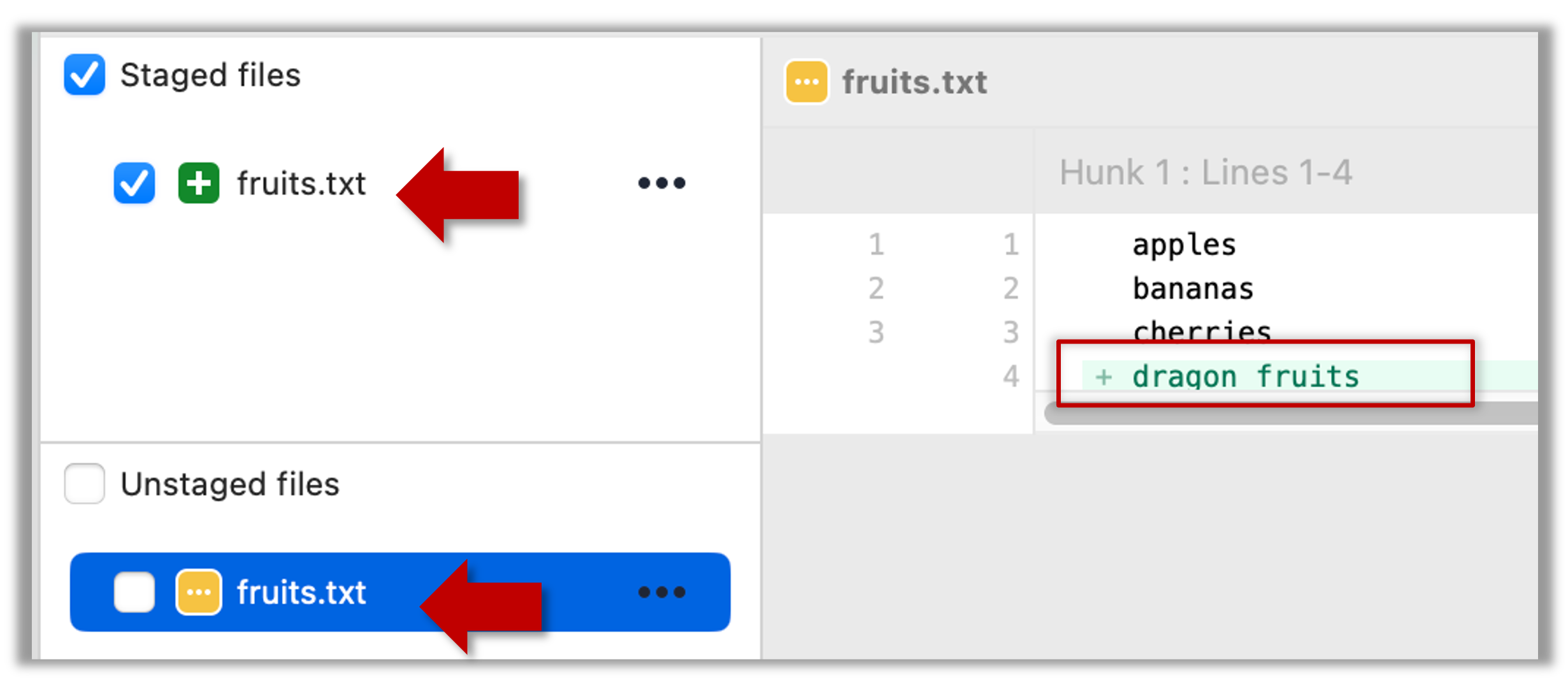

Note how fruits.txt appears in the Staged files panel as well as 'Unstaged files'.

3 Stage the file again, the same way you added/staged it earlier.

4 Verify that Git no longer sees it as 'modified', similar to step 2.

done!

Staging applies regardless of whether a file is currently tracked.

- Staging an untracked file will both begin tracking the file and include it in the next snapshot.

- Staging an already tracked file will simply mark its current changes for inclusion in the next commit.

Git also supports fine-grained selective staging i.e., staging only specific changes within a file while leaving other changes to the same file unstaged. This will be covered in a later lesson.

Git does not track empty folders. It tracks only folders that contain tracked files.

You can test this by adding an empty subfolder inside the things folder (e.g., things/more-things) and checking if it shows up as 'untracked' (it will not). If you add a file to that folder (e.g., things/more-things/food.txt) and then staged that file (e.g., git add more-things/food.txt), the folder will now be included in the next snapshot.

PRO-TIP: Applying a Git command to multiple files in one go

When a Git command expects a list of files or paths as a parameter (as the git add command does), these parameters are known as pathspecs — patterns that tell Git which files or directories to operate on. Pathspecs can be simple file names, directory names, or more complex patterns.

Here are some common ways to write them, shown with examples using the git add <pathspec> command:

-

Specify multiple files, separated by spaces:

git add f1.txt f2.txt data/lists/f3.txt # stages the specified three files -

Use a glob pattern:

git add '*.txt' # stages all .txt files in the current directoryQuoting the glob pattern is recommended so your shell doesn’t expand it before Git sees it.

-

Use

.to indicate 'all in the current directory and subdirectories':git add . # stages all files in current directory and its subdirectories -

Specific directory, to indicate 'this directory and its subdirectories':

git add path/to/dir # stages all files in path/to/dir and its subdirectories -

Negated pathspecs, to indicate 'except these':

git add . ':!*.log' # stage everything except .log files

Git supports combining these features — for example, you could add all .txt files except those in a certain folder using:

git add '*.txt' ':!docs/*.txt'

EXERCISE: stage-fright

DETOUR: Unstaging Changes

You can unstage a staged file, which simply removes it from the staging area but keeps the changes in your working directory. This is useful if you later realise that you don’t actually want to include a staged file in the next commit — perhaps you staged it by mistake, or you want to include that change in a later commit.

To unstage a file you added or modified, run

git restore --staged <pathspec>. This command removes the file from the staging area, leaving your working directory untouched.git restore --staged plan.txt budget.txt data/list.txtIf your repo does not have any commits yet,

git restore --stagedwill fail with the error fatal: could not resolve HEAD.

The remedy is to usegit reset <pathspec>instead.git reset plan.txtIn fact,

git resetis an alternative way of unstaging files, and it works regardless of whether you have any commits.Wait. Then why does

git restore --stagedexists at all, given it is more verbose and doesn't even work in some special cases?

Answer: It is still considered the "modern" way of unstaging files (it was introduced more recently), because it is more intuitive and purpose-specific -- whereas thegit resetserves multiple purposes and, if used incorrectly, can cause unintended consequences.The

restorecommand can accept multiple files/paths as input, which means you can use the notation for specifying multiple files. For example, to unstage all changes you've staged, you can use thegit restore --staged .To unstage a file deletion (staged using

git rm), use the same command as above. It will unstage the deletion and restore the file in the staging area.

If you also deleted the file from your working directory, you may need to recover it separately withgit restore <file-name(s)>git restore data/list.txt data/plan.txtTo 'nuke' all changes (i.e., get rid of all staged and unstaged changes to tracked files), you can add the

--worktreeflag to thegit restore --staged <pathspec>command.git restore --staged --worktree . # nuke all changes in current folder and subfolders

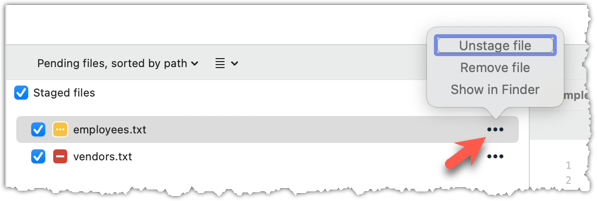

To unstage a file, locate the file among the staged files section, click the ... in front the file, and choose Unstage file:

EXERCISE: staging-intervention

Related DETOUR: Staging File Deletions

When you delete a tracked file from your working directory, Git doesn’t automatically assume you want that change to be part of your next commit. To tell Git you intend to record a file deletion in the repository’s history, you need to stage the deletion explicitly.

That aspect is covered in the tour Staging File Deletions given in the lesson T1L5. Saving a Snapshot.

After staging, you can now proceed to save the snapshot, aka creating a commit.

Saving a snapshot is called committing and a saved snapshot is called a commit.

A Git commit is a full snapshot of your working directory based on the files you have staged, more precisely, a record of the exact state of all files in the staging area (index) at that moment -- even the files that have not changed since the last commit. This is in contrast to other revision control software that only store the in a commit. Consequently, a Git commit has all the information it needs to recreate the snapshot of the working directory at the time the commit was created.

A commit also includes metadata such as the author, date, and an optional commit message describing the change.

A Git commit is a snapshot of all tracked files, not simply a delta of what changed since the last commit.

Assuming you have previously staged changes to the fruits.txt, go ahead and create a commit.

1 First, let us do a sanity check using the git status command.

git status

On branch master

No commits yet

Changes to be committed:

(use "git rm --cached <file>..." to unstage)

new file: fruits.txt

2 Now, create a commit using the commit command. The -m switch is used to specify the commit message.

git commit -m "Add fruits.txt"

[master (root-commit) d5f91de] Add fruits.txt

1 file changed, 5 insertions(+)

create mode 100644 fruits.txt

3 Verify the staging area is empty using the git status command again.

git status

On branch master

nothing to commit, working tree clean

Note how the output says nothing to commit which means the staging area is now empty.

Click the Commit button, enter a commit message (e.g. add fruits.txt) into the text box, and click Commit.

done!

EXERCISE: grocery-shopping

DETOUR: Staging File Deletions

When you delete a tracked file from your working directory, Git doesn’t automatically assume you want that change to be part of your next commit. To tell Git you intend to record a file deletion in the repository’s history, you need to stage the deletion explicitly.

When you stage a deleted file, you’re adding the removal of the file to the staging area, just like you’d stage a modified or newly created file. After staging, the next commit will reflect that the file was removed from the project.

Note that staging a file deletion matters only if there is at least one commit in the repository. Before any commits are made, there is no file history, so deletions have no effect on the repository.

To delete a file and stage the deletion in one go, you can use the git rm <pathspec> command. It removes the file from the working directory and stages the deletion at the same time.

git rm data/list.txt plan.txt

If you’ve already deleted the file manually (for example, using rm or deleting it in your file explorer), you can still stage the deletion using the git add <pathspec> command. Even though the file no longer exists, git add records its deletion into the staging area.

git add data/list.txt

Unstaging file deletions is covered in the tour Unstaging Changes given in the lesson T1L4. Specifying What to Include in a Snapshot.

Staging a file deletion is done similar to staging other changes.

Related DETOUR: Updating the Last Commit

Git allows you to amend the most recent commit. This is useful when you realise there’s something you’d like to change — e.g., fix a typo in the commit message, or to exclude some unintended change from the commit.

That aspect is covered in the tour Updating the Last Commit given in the lesson T5L3. Reorganising Commits.

Related DETOUR: Resetting Uncommitted Changes

At times, you might need to get rid of uncommitted changes so that you have a fresh start to the next commit.

That aspect is covered in the tour Resetting Uncommitted Changes given in the lesson T4L5. Rewriting History to Start Over.

Related DETOUR: Undoing/Deleting Recent Commits

How do you undo or delete the last few commits if you realise they were incorrect, unnecessary, or done too soon?

That aspect is covered in the tour Undoing/Deleting Recent Commits given in the lesson T4L5. Rewriting History to Start Over.

It is useful to be able to visualise the commits timeline, aka the revision graph.

Git commits form a timeline, as each corresponds to a point in time when you asked Git to take a snapshot of your working directory. Each commit links to at least one previous commit, forming a structure that we can traverse.

A timeline of commits is called a branch. By default, Git names the initial branch master -- though many now use main instead. You'll learn more about branches in future lessons. For now, just be aware that the commits you create in a new repo will be on a branch called master (or main) by default.

gitGraph

%%{init: { 'theme': 'default', 'gitGraph': {'mainBranchName': 'master (or main)'}} }%%

commit id: "Add fruits.txt"

commit id: "Update fruits.txt"

commit id: "Add colours.txt"

commit id: "..."

Git can show you the list of commits in the Git history.

Preparation Use the things repo you created in a previous lesson. Alternatively, you can use the commands given below to create such a repo from scratch.

mkdir things # create a folder for the repo

cd things

git init

echo -e "apples\nbananas\ncherries\ndragon fruits" > fruits.txt

git add fruits.txt

git commit -m "Add fruits.txt"

You can copy-paste a list of commands (such as commands given above), including any comments, to the terminal. After that, hit enter to run them in sequence.

1 View the list of commits, which should show just the one commit you created just now.

You can use the git log command to see the commit history.

git log

commit ... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add fruits.txt

Use the Q key to exit the output screen of the git log command.

Note how the output has some details about the commit you just created. You can ignore most of it for now, but notice it also shows the commit message you provided.

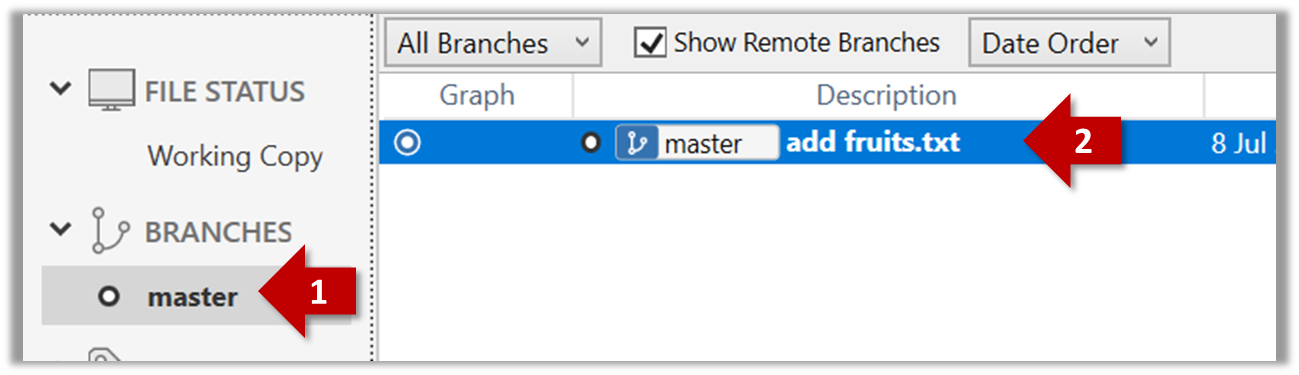

Expand the BRANCHES menu and click on the master to view the history graph, which contains only one node at the moment, representing the commit you just added. For now, ignore the label master attached to the commit.

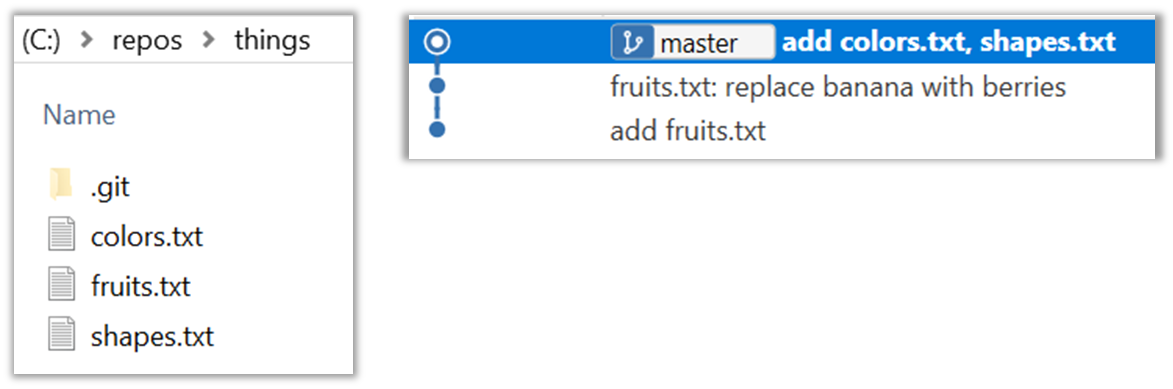

2 Create a few more commits (i.e., a few rounds of add/edit files → stage → commit), and observe how the list of commits grows.

Here is an example list of bash commands to add two commits while observing the list of commits

echo "figs" >> fruits.txt # add another line to fruits.txt

git add fruits.txt # stage the updated file

git commit -m "Insert figs into fruits.txt" # commit the changes

git log # check commits list

echo "a file for colours" >> colours.txt # add a colours.txt file

echo "a file for shapes" >> shapes.txt # add a shapes.txt file

git add colours.txt shapes.txt # stage both files in one go

git commit -m "Add colours.txt, shapes.txt" # commit the changes

git log # check commits list

The output of the final git log should be something like this:

commit ... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

commit ...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Insert figs into fruits.txt

commit ...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: ...

Add fruits.txt

SIDEBAR: Working with the 'less' pager

Some Git commands — such as git log— may show their output through a pager. A pager is a program that lets you view long text one screen at a time, so you don’t miss anything that scrolls off the top. For example, the output of git log command will temporarily hide the current content of the terminal, and enter the pager view that shows output one screen at a time. When you exit the pager, the git log output will disappear from view, and the previous content of the terminal will reappear.

command 1

output 1

git log

→

commit f761ea63738a...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add colours.txt

By default, Git uses a pager called less. Given below are some useful commands you can use inside the less pager.

| Command | Description |

|---|---|

q | Quit less and return to the terminal |

↓ or j | Move down one line |

↑ or k | Move up one line |

Space | Move down one screen |

b | Move up one screen |

G | Go to the end of the content |

g | Go to the beginning of the content |

/pattern | Search forward for pattern (e.g., /fix) |

n | Repeat the last search (forward) |

N | Repeat the last search (backward) |

h | Show help screen with all less commands |

If you’d rather see the output directly, without using a pager, you can add the --no-pager flag to the command e.g.,

git --no-pager log

It is possible to ask Git to not use less at all, use a different pager, or fine-tune how less is used. For example, you can reduce Git's use of the pager (recommended), using the following command:

git config --global core.pager "less -FRX"

Explanation:

-F: Quit if the output fits on one screen (don’t show pager unnecessarily)-R: Show raw control characters (for coloured Git output)-X: Keep content visible after quitting the pager (so output stays on the terminal)

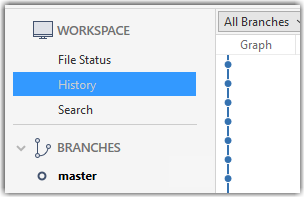

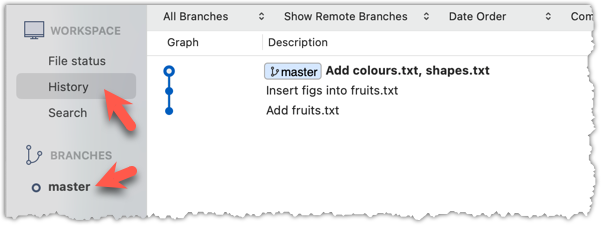

To see the list of commits, click on the History item (listed under the WORKSPACE section) on the menu on the right edge of Sourcetree.

After adding two more commits, the list of commits should look something like this:

done!

The Git data model consists of two types of entities: objects and refs (short for references). In this lesson, you will encounter examples of both.

A Git revision graph is a visualisation of a repo's revision history, consisting of one or more branches. First, let us learn to work with simpler revision graphs consisting of one branch, such as the one given below.

- Nodes in the revision graph represent commits. A commit is one of four main types of Git objects. For completeness, the other three are:

- blob (short for binary large object): stores the contents of a file

- tree: represents a directory and records the hierarchy of its contents by referencing blobs and other trees

- tag (specifically, annotated tag): a label-like object that can store additional metadata and point to a specific commit

- A commit is identified by its SHA value. A SHA (Secure Hash Algorithm) value is a unique identifier generated by Git to represent each commit. It is produced by using SHA-1 (i.e., one of the algorithms in the SHA family of cryptographic hash functions) on the entire content of the commit. It's a 40-character hexadecimal string (e.g.,

f761ea63738a67258628e9e54095b88ea67d95e2) that acts like a fingerprint, ensuring that every commit can be referenced unambiguously. That is, every commit has a unique SHA-1 hash value. - A commit is a full snapshot of the working directory, constructed based on the previous commit, and the changes staged. That means each commit (except the initial commit) is based on a another 'parent' commit. Some commits can have multiple parent commits -- we’ll cover that later.

Given every commit has a unique hash, the commit hash values you see in our examples will be different from the hash values of your own commits, for example, when following our hands-on practicals.

Edges in the revision graph represent links between a commit and its parent commit(s). In some revision graph visualisations, you might see arrows (instead of lines) showing how each commit points to its parent commit.

Git uses refs to name and keep track of various points in a repository’s history. These refs are essentially 'named-pointers' that can serve as bookmarks to reach a certain point in the revision graph using the ref name.

In the revision graph above, there are two refs master and ←HEAD.

- master is a branch ref. A branch ref points to the latest commit on a branch. In this visualisation, the commit shown alongside the ref is the one it points to i.e.,

C3.

When you create a new commit, the branch ref of the branch moves to the new commit. - ←HEAD is a special ref that typically points to the current branch and moves along with that branch ref. In this example, it is pointing to the

masterbranch.

In certain cases, theHEADmay point directly to a specific commit instead of a branch. This situation is called a "detachedHEAD", which will be covered in a later lesson.

Target Use Git features to examine the revision graph of a simple repo.

Preparation Use a repo with just a few commits and only one branch.

1 First, use a simple git log to view the list of commits.

git log

commit f761ea63738a... (HEAD -> master)

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

commit 2bedace69990...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Sat ...

Add figs to fruits.txt

commit d5f91de5f0b5...

Author: ... <...@...>

Date: Fri ...

Add fruits.txt

Given below the visual representation of the same revision graph. As you can see, the log output shows the refs slightly differently, but it is not hard to see what they mean.

2 Use the --oneline flag to get a more concise view. Note how the commit SHA has been truncated to first seven characters (first seven characters of a commit SHA is enough for Git to identify a commit).

git log --oneline

f761ea6 (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

d5f91de Add fruits.txt

3 The --graph flag makes the result closer to a graphical revision graph. Note the * that indicates a node in a revision graph.

git log --oneline --graph

* f761ea6 (HEAD -> master, origin/master) Add colours.txt, shapes.txt

* 2bedace Add figs to fruits.txt

* d5f91de Add fruits.txt

The --graph option is more useful when examining a more complicated revision graph consisting of multiple parallel branches.

Click the History to see the revision graph.

- In some versions of Sourcetree, the

HEADref may not be shown -- it is implied that theHEADref is pointing to the same commit the currently active branch ref is pointing.

done!

At this point: You should now be able to initialise a Git repository in a folder and commit snapshots of its files at times of your choice. So far, you did not learn how to actually make use of those snapshots (other than to show a list of them) -- we will do that in later tours.

What's next: Tour 2: Backing up a Repo on the Cloud